Over the past year, we have all witnessed the increasing acts of hate and violence against Asian Americans, particularly against women and the elderly. Some have tried to cast these incidents as a new trend. Yet, for those of us who identify as part of the Asian American, Native Hawaiian, and Pacific Islander (AANHPI) diaspora, we are quite familiar with the longstanding discrimination and violence experienced by our communities, as well as the ongoing marginalization and invisibility that has often kept our communities relegated to the edges of diversity, equity, accessibility, and inclusion (DEAI) efforts. While it has been lovely to see a sea of #StopAsianHate on my social media feeds, I wonder how much true commitment there is for the difficult work in the coming weeks, months, and years. I don’t expect anti-Asian hate to disappear overnight when it has existed for generations. I also recognize that the efforts against racism and xenophobia experienced by Asian and immigrant communities must occur in mutual solidarity with efforts to address systemic racism experienced by Black, Indigenous, and other racial/ethnic communities and marginalized communities.

Some of the roots of anti-Asian racism and xenophobia trace back to the mid-nineteenth century, when the first waves of Chinese immigrants came to the US during the gold rush in search of new beginnings. But instead of opportunity, they often endured stigmatization, mob attacks, and lynchings across the US. Ultimately, these xenophobic attitudes resulted in passage of the Page Act of 1875, which stereotyped Asian women as prostitutes and prohibited their immigration, and the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, which excluded a specific nationality from naturalization for the first time in US history. In the coming decades, this legislation would be followed by other exclusionary policies that essentially barred immigration from most countries across Asia and the Pacific.

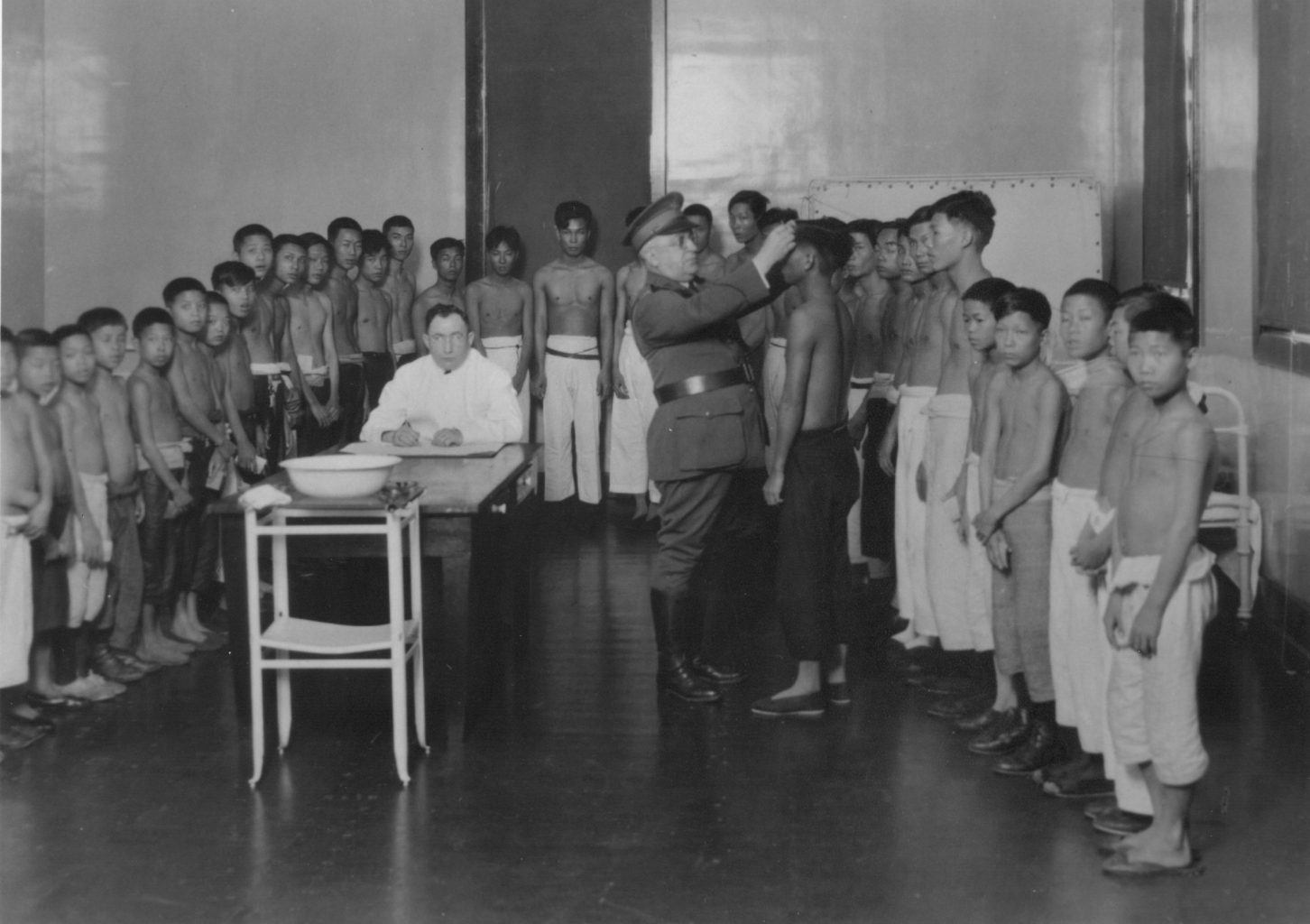

A potent symbol of this era of exclusion is the former US Immigration Station at Angel Island in San Francisco, an equivalent to Ellis Island except that it was built for the purpose of keeping Asian and Pacific Islander immigrants out. From 1910 to 1940, over five hundred thousand immigrants from eighty different countries (particularly from the Asia and Pacific region), were processed, interrogated, or detained on Angel Island. During their time there, Asian detainees were segregated from their European counterparts, faced more invasive medical screening, lived in more crowded and unsafe conditions, and endured more intensive questioning from immigration inspectors.

When I first visited this site two years ago, I was overwhelmed by a sea of mixed emotions. As an immigrant whose family had moved from Thailand to Texas in the 1970s, I could resonate with the sense of hope that led Angel Island’s detainees to leave their families and homes. Walking through the detention barracks, I could also feel deep in my bones the desperation, frustration, and sadness they must have felt. And I felt angry that I was never taught about this important part of US history (or any AANHPI history, aside from two paragraphs on Japanese American incarceration during World War II) in school.

In late 2019, I joined the staff of the Angel Island Immigration Station Foundation (AIISF), the primary nonprofit partner working with Angel Island State Park to preserve the station’s buildings, its histories, and its stories. Much of our work over the past seven years has focused on preventing the site’s hospital from collapsing, renovating the entire building, and installing new permanent exhibits in the hospital, renamed and repurposed as the Angel Island Immigration Museum. In curating the museum’s exhibits over the past year, I felt a deep-seated sense of responsibility as an Asian immigrant to ensure that more people learn about this history of Asian exclusion. Simultaneously, my twenty-five-year career in HIV prevention, public health advocacy, and racial justice reminded me of the importance of solidarity, creating spaces for dialogue and discussion, and the need to be inclusive of other communities at the same time I am fighting for inclusion for the communities I identify with. Thus, our curation team considered opportunities to include newer stories and histories of immigrants who have come to the US after Angel Island ceased functioning as an immigration station, for example current day refugees and asylum seekers along the Southern border.

Over the past months, I’ve also reflected on what is important for me to hold central in my work at AIISF, as well as how our current times are calling forth historical sites and museums to rethink our purposes and programs. At a moment when there is increased attention on AANHPI communities, and perhaps an increased motivation to tell these stories, I humbly offer the following:

Some of the most important and harmful AANHPI narratives to beware of and to work together to dismantle are:

- The model minority myth. Asian communities are often mistakenly viewed as universally wealthy and well-educated, and perhaps immune to experiencing racism as a result. Yet, AANHPIs constitute a diverse constellation of over fifty different ethnic groups who speak one hundred different languages. Analyzing detailed socioeconomic data about these groups reveals a wide range of experiences. This myth not only misrepresents the struggles AANHPI communities face, but also creates a wedge between our communities and other racial/ethnic communities.

- The perpetual foreigner. Regardless of how long an individual, their family, or their community has lived in the US, Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders (and other immigrant groups) are often viewed as not “fully” American.

- Invisibility. All too often, DEAI efforts fail to meaningfully include AANHPI histories and contexts. Outreach and engagement efforts overlook established or emerging AANHPI communities. Southeast Asian, Native Hawaiian, and Pacific Islander communities in particular are among the most overlooked due to the relative size of their communities.

- Female exoticization and male demasculinization. AANHPI women are often stereotyped as being submissive, hypersexualized, exoticized, and fetishized. In contrast, AANHPI men are often demasculinized and desexed. Both can have devastating impacts on mental health and violence against women.

A few easy ways to show your allyship for AANHPI communities beyond posting on social media include:

- Reaching out. It’s likely that your AANHPI friends and colleagues are hurting. The recent killings of six Asian women in Atlanta and the increasing number of vicious attacks on Asian elders has left many of us fearful, traumatized, and angered. Even if you don’t know exactly what to say, a simple “I’m so sorry this is happening” can be meaningful.

- Self-reflection and learning. Take responsibility for reassessing your own learned prejudices and stereotypes. Make the effort to educate yourself about AANHPI communities. Watch PBS’s Asian Americans series. Skim the Smithsonian Asian Pacific American Center’s website. Learn about Angel Island’s history. Take a crash course in AANHPI history.

- Not asking us “Where are you from,” or worse, “Where are you really from?” While you might be asking these questions from a place of genuine curiosity, the message we hear is, “You aren’t from here.”

Some (hopefully transferable) lessons learned from my public health career:

In public health research, there is an approach known as community-based participatory research (CBPR). The premise is that actively involving the community builds trust and credibility, empowers community involvement in decision-making, and results in a better final product. Applying these CBPR principles to the museum sector potentially offers the following promising practices:

- Create and sustain multiple partnerships. Do not rely on just one individual or one community organization (unless there truly is only one in your area). Recruit and support collaborations with organizations that represent specific AANHPI groups (e.g., Vietnamese Association), pan-AANHPI groups (e.g., Asian & Pacific Islander Community Health Centers), and multiple racial/ethnic groups (e.g., immigrant support organizations)

- Promote equity in the partnerships. Develop formal memoranda of understanding and compensate your community partners for their time/effort. Ensure that they have an equitable role in decision-making related to grants, exhibits, and other projects.

Some final considerations to make DEAI efforts more meaningfully inclusive of AANHPIs:

- Recruit staff at all levels with diverse and extensive work experience in AANHPI communities. Assess how well AANHPI communities (particularly from Southeast Asian, Native Hawaiian, and Pacific Islander communities) are included amongst your leadership, staffing, and volunteers.

- Consider to what degree your exhibits, programs, and stories can include a fuller spectrum of AANHPI communities. Examine local census data to develop a better understanding of the largest AANHPI communities in your area.

- Provide materials translated in AANHPI languages. One out of three Asians has limited English proficiency. While it may not be possible to provide translation or interpretation resources in all AANHPI languages, census data can help prioritize the languages that might be most important.

In many AANHPI families and cultures, we are taught from an early age to respect authority, to avoid drawing undue attention to ourselves, and to keep our heads down. But from my HIV advocacy days, I learned early on that silence equals death, so it’s important to stand up and to be vocal. When you witness the events around you, when you see that certain groups are underrepresented in your institution’s staffing, when you recognize that your programs are missing pockets of communities—will you be a silent bystander or an active upstander?

Author’s Note: While the terms “Asian Pacific Islander” (API), “Asian and Pacific Islander” (A&PI), or “Asian American Pacific Islander” (AAPI) are most commonly used, I personally use the term Asian American, Native Hawaiian, and Pacific Islander (AANHPI). I do so at the request of and in solidarity with my Native Hawaiian friends and colleagues who have enlightened me about the continued invisibility of Native Hawaiian communities. Different communities and different geographic regions may have different preferences for which term is used.

Edward, thank you for this insightful and very helpful perspective! I especially appreciate the suggestions on ways we can show allyship for AANHPIs. These are personal actions — ones that each of us can take. And they mean so much. As an ally and as part of the AANHPI community (through my family — spouse, children, in-laws, and more), I know the truth of your words.

I see the vital stories that the Angel Island Immigration Station holds, and I look forward to the time when we can visit again.

Thank you for this article. I will be sharing it with the St Peter State Hospital Museum Committee, St Peter, MN. While the identified group is different, you have laid out a great process for us to identify, explore and add more diversity, equity, accessibility and inclusion to our exhibits and learning activities.

Fantastic suggestions, Ed, and I encourage everyone to view the exhibits at the Angel Island Immigration Museum – both for content and for a model of excellence in exhibitions.