One challenge we’ve all probably faced in collaborative program and exhibit development/design is creating a space for open and honest feedback. We know candid feedback is crucial for aligning the outcome of a project with its stated goals and needs, but without facilitation and support, it can sometimes focus on the negative, feel personal, or give undo weight to the loudest or most powerful person in the room.

At the Monterey Bay Aquarium, we’ve had a lot of success addressing this problem by helping our teams give feedback in a more structured way, instead of in a free-for-all. There are many established feedback routines amongst design thinking professionals and other disciplines, but we have developed a simple structure of our own that has had particular success in both our education and exhibition development processes. Over time, this structure has become a routine that places value on the ideas rather than the person presenting them, encourages more participation in feedback-giving, and supports the forward momentum of ideas. We call it Excite, Build, Consider (EBC).

In developing this feedback structure, we wanted to generate feedback that 1) made our staff feel valued for their ideas and work (regardless of their position and experience); 2) provided suggestions for next steps; and 3) acknowledged what was lacking, missing, or should be changed in the program prototypes. To do all of this, we needed to be very careful with the language that we wrote into the frame. The Excite, Build, Consider framework was the result of meeting these challenges.

| Question to the group | Responses begin with … | |

| Excite | What about this idea are you excited about? | I am excited about… because… |

| Build | What ideas do you have to build on what was said? | You could build on this idea by… |

| Consider | What do you think we should consider changing? | Have you considered…? |

After developing the framework, we tried it out for the first time in 2015 with a small group of education staff who were designing learning experiences, asking them to iterate on their ideas given some peer feedback. Afterwards, we asked them to reflect on the experience, then revised the framework and process of using it based on their reflections. The following table outlines each observation and the actions taken to improve the EBC framework. We share it with you as advice on what worked and how it can be most successful.

| Observations from Staff | Action/Advice |

| The framework encouraged participation from most members, but it would take time for all staff to feel comfortable providing feedback. | ● Incorporate the feedback frame into multiple stages of the design/development process. This helps to normalize the process of speaking about each other’s work. |

| It was helpful to hear the same language structure being used by everyone, managers/leadership included. | ● Be firm in the application of the language into the feedback sessions. You may need to remind participants of the sentence starters often in the beginning.

● Ask the staff to reflect on the experience of using EBC and provide insights on its utility. |

| Some program designers became defensive when responding to feedback if they were attached to their ideas, and depending on who was giving the feedback. | ● Be sure to go through the questions in order. This helps people settle in to the feedback.

● Implement a feedback session early on in the design process, before the prototypes are developed too far. ● Create a protocol that designers do not respond to feedback in the moment it is given, but instead listen closely and decide how or if to incorporate it afterward. |

The education division has incorporated the EBC framework ever since, including during years of intense program development. The team uses it throughout the entire development process, from sharing the earliest storyboards to unveiling the final products. The framework has not only improved products, but helped each team member feel they have a platform for contributing their thoughts and can grow in their ability to give and receive feedback.

When reflecting on the process about three years in, one staff member wrote, “Don’t be afraid to speak up. Even though you process internally, make sure your team knows what you’re thinking. Make your voice be heard.” Another staff member wrote, “I don’t need to hold so tightly to ideas or my background. There’s really no ‘being right;’ it’s sharing ideas and communicating as the goal, not the product.” With consistency, the framework has contributed to an atmosphere where people are more willing to take risks and be vulnerable. In addition, it has created a more compassionate way of communicating, and eventually helped shift the culture so that there is shared power when creating new things in the division.

Excite, Build, Consider in Exhibition Development & Design

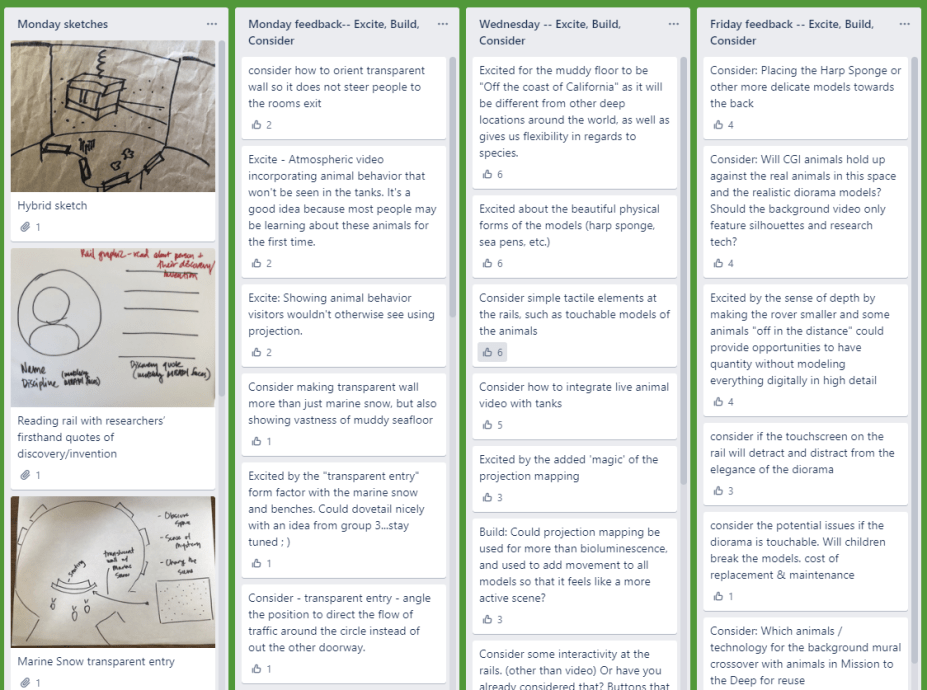

Shortly after we finalized the EBC framework, Joey, who had been in the education division for six years, joined the exhibitions team as a Project Manager. There, too, the framework became a regular routine during design sprints, as the team collaboratively developed the conceptual design for its newest exhibition, Into the Deep: Exploring Our Undiscovered Ocean. They used it in their initial brainstorm (see “Monday sketches” in the image below) and again as their ideas became more and more detailed throughout the weeks.

Since we were working remotely in 2020, some of the process was different from in the past. The team used Trello, an online collaboration tool, to share feedback, which allowed them to write out their feedback instead of saying it aloud in front of a large group, and to “thumbs up” someone else’s feedback. (This meant all the feedback was automatically documented—a project manager’s dream.) This structure helped democratize feedback among the staff of varied disciplines and experience levels. It didn’t matter if you were a new designer or a VP; everyone’s comments were equally important. One voice didn’t dominate the conversation, because we took independent time (muted, video off) to write our feedback up all at the same time. And the thumbs-up function allowed us to see if there was consensus across disciplines and experience levels.

Just as it did in the education division, the EBC feedback structure helped the team both give and really hear feedback from each other, and ultimately resulted in a better-rounded, more thoughtful product. For example, in the process of creating the visitor experience in the seafloor gallery of the new exhibition, the collective feedback cards showed the team was “excited” about the idea of a realistic diorama showcasing local deep-sea species that they might not be able to exhibit live. A “build” piece of feedback resulted in some prototyping with projection mapping. And a “consider” piece of feedback led them to think about the tactile elements they could add to increase interactivity.

Supporting Culture & Iteration

In using the EBC feedback structure, we’ve been most impressed with how quickly it can become a habit and how quickly teams buy into it. We’ve seen that this framework can both support the development of a more trusting collaborative culture and spark ideas to improve a particular product. We look forward to hearing how other institutions try and adapt the Excite, Build, Consider feedback structure in their own contexts.

Skip over related stories to continue reading article

Comments