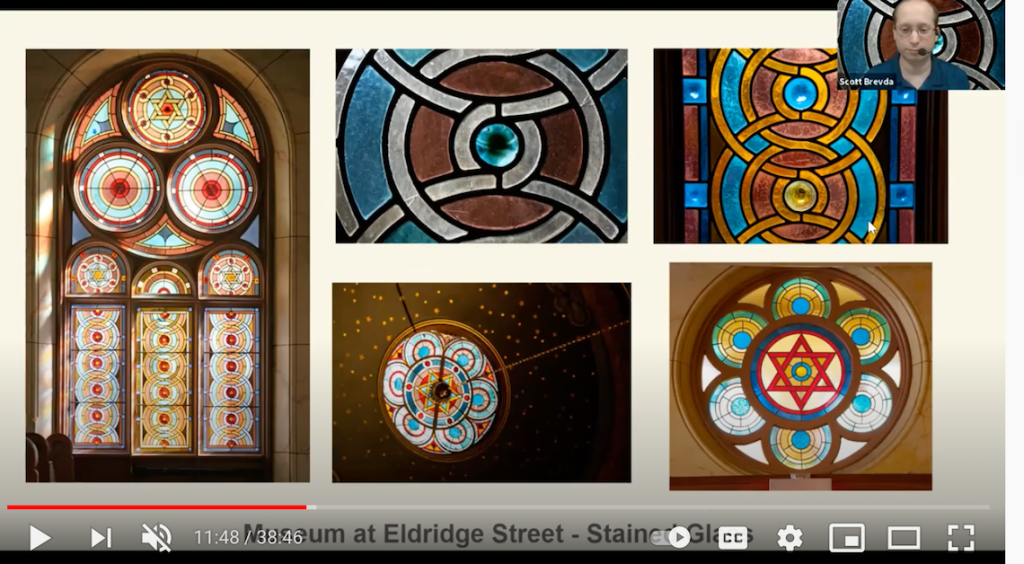

Envision a group of schoolchildren standing before you, giddy with anticipation and excitement. In front of them are two elongated rectangular wooden doors, which, once opened, will transport them to another time. The doors swing open and laid out before the students is a massive space with star-studded domed ceilings painted the color of the night sky, and a rainbow of light pouring in from dozens of stained-glass windows adorned in interlocking circles crowned with Stars of David. Directly ahead, affixed into the synagogue’s eastern wall, a massive and otherworldly blue orb consisting of twelve hundred pieces of vintage stained glass, five pointed stars, and silicone substrate emits thousands of cracks of light into the sanctuary. As the students step foot inside the space, heads roll back, mouths hang open, and a collective “ohhhh” reverberates throughout. It is an expression of pure awe and wonder.

This is a scene I have witnessed countless times leading field trips at the Museum at Eldridge Street. Constructed in 1887 as Eldridge Street Synagogue, our building was the first grand house of worship built by Eastern European Jews in the United States, meant to showcase both the permanence and rising affluence of this immigrant community in American society. With its eclectic combination of Gothic, Moorish, and Romanesque architecture, it has been deemed an “architectural Sabbath” by historians—a sanctuary in the city where people could go and experience beauty, wonder, and spiritual restoration.

Unlike many museums, which house collections and gallery space, our building remains our primary artifact and chief work of art. Today the museum welcomes visitors from all over the world, and prior to the pandemic this included an annual visitation of over five thousand Pre-K to twelfth-grade students. Whether students are coming to learn about immigration, Jewish traditions, or geometric concepts, a key component of all these visits is interacting with a space that was designed to be used by people. At Eldridge, a feeling of wonder comes in a variety of forms, from standing in the wooden floor grooves left behind by our original congregants, to bathing in a rainbow of light, to writing a poem while sitting in a 134-year-old pew.

But when our museum shut down in March 2020, the concept of the field trip was completely flipped on its head. As a museum whose physical space is the entire purpose of the visitor experience, how, we wondered, could we even begin to capture those wondrous and multisensory experiences in a virtual format?

Skip over related stories to continue reading articleTo help us answer this question, we started by collecting feedback from the local teachers with whom we are fortunate to have long-standing relationships, asking them in a survey and in one-one-on-one follow up meetings what types of virtual programming they were interested in during the upcoming school year.

The teachers who attended these meetings were predominantly from the schools in our surrounding Lower East Side and Chinatown communities which had historically utilized our programming the most throughout the school year. The majority of these schools are Title 1, serving low-income first- and second-generation immigrants from China and Latin America.

These conversations were extremely important for our planning, as teachers told us what was and was not working for them in the virtual classroom and suggested how our programming could best address the emotional needs of students. They also expressed an openness towards us trying new things and solidified themselves as partners who would provide feedback and guidance as we launched our virtual programming in the fall. In exchange for this openness to experimentation, we waived the programming fees for the 2020-2021 school year.

Based on their feedback, and on feedback from past years that many students considered seeing our Gothic stained-glass windows a highlight of their visit, we piloted a virtual workshop called Vibrant Light: Stained Glass Learn and Do. Developed and by the museum’s Senior Educator, the program introduced families to the history and purpose of stained glass, followed by a stained glass making activity at the end of the program.

One of our priorities with the program format was to convey through media the feeling of being inside the museum, immersed in the light of the stained-glass windows. We decided the most immersive option would be video and music, and we were fortunate enough to have existing panoramic footage of our main sanctuary, including close-up views of the windows, set to an accompaniment of soft-playing piano music. During the program, we used this footage as part of a virtual tour of the space. After showing examples of stained glass from places around the world, we came to a picture of the museum’s façade and asked the children to share their observations about the building. We then invited them to “step inside” by watching the video of the building’s interior. Before playing the video, we encouraged them to share their reactions to the space by either by typing or posting emojis in the chat.

During the minute and thirty seconds that the video ran, we saw children posting heart and wonder-faced emojis on their screens and commenting in the chat how beautiful the building was. Some who had been acting a little restless at the start of the program were now calm and focused on their screen. Even though the group was muted, I could see more than one joyful expression in the video grid. I realized that, although we were separated by small black squares and a terrible pandemic, those things couldn’t keep us from connecting and experiencing a moment of wonder together.

Based on the success of this pilot program, we decided that come fall we would add a stained-glass workshop to our roster of virtual K-12 programming. We felt this would work especially well for kindergarten and elementary school students, as the content tied nicely into New York State learning standards in both math and art, including the study and function of different types of light. The essential question of the program became, “How can light be used to create art and tell stories?”

In September, we launched a back-to-school email campaign announcing our virtual program offerings for the school year with a spotlight on our new stained-glass program. The majority of teachers who requested the program taught kindergarten through second grade and were based in local Title 1 schools. From the reservation requests, we learned that teachers wanted the stained-glass program because it fit into units of study on light and geometry and because there was a hands-on art component. In the case of one class, our virtual program served as a substitution for a yearly subway excursion to see examples of public stained-glass art installations.

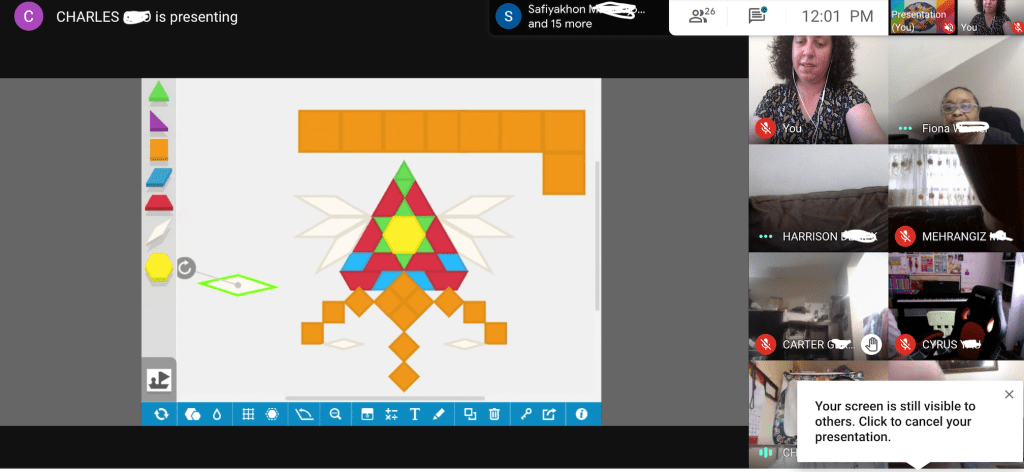

Scheduling these virtual programs was a highly collaborative process. Through email correspondence and video calls, teachers took the time to walk through the programming format and offer guidance and feedback. Although we had developed an art project that utilized downloadable templates of our stained-glass windows, teachers pointed out that not all their students had access to printers or basic art materials. We worked together to come up with projects that were accessible and adaptable. Some examples included using watercolors and paper towel rolls to create interlocking circles inspired by the circular patterns found in the museum’s stained-glass windows or working with teachers to create art kits. No matter what the project was, we were able to ensure that everybody could participate.

Because the students attending these programs were all from New York City, we adapted the format by showcasing examples of stained glass found across the city. We became the animals in Naomi Campbell’s subway installation Animal Tracks at the East Tremont Street Station, played history trivia with the scenes found in the iconic windows at St. John the Divine, and made our bodies into the trees and flowers depicted in the Tiffany windows at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. A surprising moment of wonder came during a program with a second grade class, when we presented an installation by the artist Tom Fruin. The piece, titled Watertower, consists of a kaleidoscope of colorful plexiglass in the shape of an iconic New York City water tower. Students could barely contain their excitement and began calling out how they saw water towers from their apartment windows or had seen the Watertower installation while crossing the Manhattan Bridge. They were amazed to discover that even something as ordinary as a water tower could also be a work of art.

When the time came for us to “welcome” students inside Eldridge Street, we asked them to focus on how the footage of the synagogue made them feel. Just like in our summer pilot program, they posted their feelings through emojis and comments in the chat. Afterwards, when asked how seeing the space made them feel, some students spoke about a feeling of calm and peace, while others shared connections about how the synagogue’s stained glass reminded them of the churches and mosques that they worshipped in. Students were especially excited to create their own stained-glass projects, and while everyone started off with the same materials, each came away with their own unique interpretation of stained glass. The feedback we received in surveys was overwhelmingly positive, with some teachers writing that the workshop brought the building to their students in “real time” and gave them a “hands-on” opportunity to engage with the space. It was especially rewarding when teachers would email us photos and screenshots of student projects. From these surveys and student samples, we have decided that the stained-glass workshop will become a permanent offering of our virtual education programming, and we look forward to pivoting this program to in-person in the near future.

No matter what type of museum we work in, all educators have strived and struggled this past year to impart moments wonder in a virtual world. Whether you are looking to revisit your roster of virtual programs or are creating a virtual program for the first time, here are some guiding principles to help you think about creating your own moments of wonder.

1. Identify the collective “oohs and ahhs” at your museum.

Think about the moments during your onsite programs that where you have invited students to react to something. Was it a really cool science experiment? A piece of artwork? An activity or project that got students using their hands or bodies? After identifying those moments, think about how they could be adapted to a virtual format.

2. Try new things and create connections.

We are all looking for ways to create moments of wonder for our students. Whether those include video, music, or games, incorporate activities that are active and multi-sensory. Ask teachers to provide information about the class’s learning goals and prior knowledge, as this can help you think about the type of experience you create.

As an example, when a teacher shared that she usually took her students on the subway to see stained glass installations, I created an experience where we pretended to ride on the subway, complete with metro card swiping, maps, and subway sound effects.

3. Collaborate with and seek support from teachers.

Collecting surveys and evaluations is essential with any museum program, and with school programs you should create opportunities for teachers to share qualitative and anecdotal feedback. Reach out to teachers who have a history of bringing students for annual or multiyear visits. Create a teacher committee. Connect with schools in your local community and find out what their programming needs are. When piloting new programs, waive the admission fee.

Comments