The Musical Instrument Museum (MIM) in Phoenix, Arizona, celebrates music and world cultures through a multisensory experience—where guests can “travel” the globe through the sights and sounds of MIM’s geographically organized exhibits. As guests learn more about music-making, they also draw connections to and foster appreciation for a diversity of cultures.

Last year, MIM’s education team created virtual programming to serve senior communities who might not be able to visit the museum in person, developing a Zoom series for older adults in collaboration with Arizona State University (ASU). When we realized some communities needed more flexibility in access and timing than the virtual classes provided, we set out to develop an asynchronous option as well. Two new Senior Wellness video collections took shape in early 2021: one program for active seniors and one memory care version for individuals with memory loss.

The final products are a rich multimedia experience where objects come to life through music—just like in the museum experience—and seniors make music from the regions they’ve “traveled” to at MIM. In five behind-the-scenes photos, we share some steps MIM took to realize this vision and what we learned along the way. For other museums looking to create an asynchronous virtual option, we provide a few of our key takeaways in the conclusion of the article.

1. Growing a local partnership

The Senior Wellness video collections are a true collaboration, building on an existing relationship with ASU Music Therapy and Program Director Dr. Melita Belgrave. With the onset of the pandemic, MIM worked with Dr. Belgrave to develop Zoom sessions that combined aspects of the museum experience with active music-making for senior audiences impacted by COVID-19. The programs were well received, with over 550 seniors participating in Zoom sessions between May 2020 and April 2021. As the pandemic carried on, MIM saw an increasing demand for flexible, participatory ways that seniors could engage with the arts.

Skip over related stories to continue reading articleUsing the successful Zoom program as springboard, MIM and ASU decided to create the new video options to similarly bring together music therapy with the MIM experience, but in a format accessible to senior audiences anytime, anywhere. The recorded content also would also provide flexibility for older adults in different living situations, whether making music at home or with a group in senior communities.

Dr. Belgrave led teams of music therapy students to develop music therapy interventions that complement virtual tours of MIM’s galleries. They designed the interventions with a focus on physical skills (drumming, dancing, and other movement), cognitive skills such as attention and memory, and psychosocial components related to self-expression through music. The session in the photo above also includes a craft activity to make homemade shakers from everyday household materials.

What we learned: While Zoom-based classes allowed for on-screen interaction, many facilities weren’t able to share the offerings due to the synchronous nature of the timing and inability to gather in groups. We needed to provide a more flexible asynchronous option to order to reach more facilities and better serve the community.

2. Reimagining a museum visit

When setting out to bring the MIM experience to seniors who might not be able to visit in person, MIM’s team strove to create a sense of connection to the museum’s spaces by pairing a virtual tour at one of the exhibits in each of the Geographic Galleries with the music therapy activities recorded in MIM’s Music Theater.

One of the key aspects of MIM’s in-person experience is the headsets guests wear that automatically play multimedia recordings at each exhibit, showing what the instruments sound like and different performance contexts worldwide (in total, over two hundred countries are represented in the museum). With the multimedia format, we were able to offer the same kind of musical content that guests would see and hear at the museum—from a traditional Hawaiian hula to a sizhu music session at a teahouse in Shanghai, China, to a dance band playing Cuban son music in 1960s Havana.

Along with curators’ expertise shared in a guided tour of each exhibit, field footage provides the authentic soundscape and sets the stage for activities related to each country’s music. In the Ireland exhibit tour pictured above, curator Richard Walter introduced traditional Irish instruments on exhibit—such as the fiddle, button accordion, uilleann pipes, and frame drum—followed by video footage (also on display at MIM’s exhibit) of a music session from Irish band Téada.

What we learned: Re-creating MIM’s immersive, multimedia experience required post-production work. We found it helpful to focus on conveying the essence of a MIM visit, adapted to the video format.

3. Scripting a new process

Scripts were developed by MIM’s curators and music therapy students in coordination with Palmer. The material in the curator tours was written to call out highlights of each exhibit while also letting multimedia content help tell the story of music in each region.

For the music therapy portions, Palmer provided guidance on how to deliver instruction geared to the video format for virtual audiences. In many of the activities, students modeled a musical line or movement before asking participants to join. In the Chicago blues exercise pictured above, the music therapy students demonstrated three different improv parts and asked audiences to choose one person to follow along with. Many of the interventions in the series are customizable. In the same video dedicated to music of Chicago, when the students led a gospel song featuring movements such as clapping and snapping, they provided and demonstrated options to complete the activity seated in a chair or standing.

What we learned: Asynchronous programming required a more structured approach in scripting, both to keep videos within the timeframe and to keep content succinct enough to maintain interest. ASU music therapy students also had to critically frame their presentation so that it was scaffolded for an imagined audience.

4. Production and editing

Creating content for these video collections took around forty-five hours of filming, including the gallery and music therapy portions, and required the collaboration of MIM’s theater, education, and creative teams.

Along with videographers, lighting and sound design experts who regularly produce concerts in the theater lent their skills to the production.

A typical filming session with music therapy students in the theater included full run-throughs of content along with shorter takes that focused on specific performances or activities. After shooting initial footage, the multimedia team edited together various takes, added B-roll footage of instruments and exhibits, and synced and mixed audio, which was recorded separately. They also mixed in the contextual footage from MIM’s galleries and supplemental photography. Adding captions, display text, graphics, and animations, such as a plane flying across a map from Phoenix to each region visited, they created a polished final product that is both educational and fun.

What we learned: Looking for strengths across the organization makes for a great collaboration.

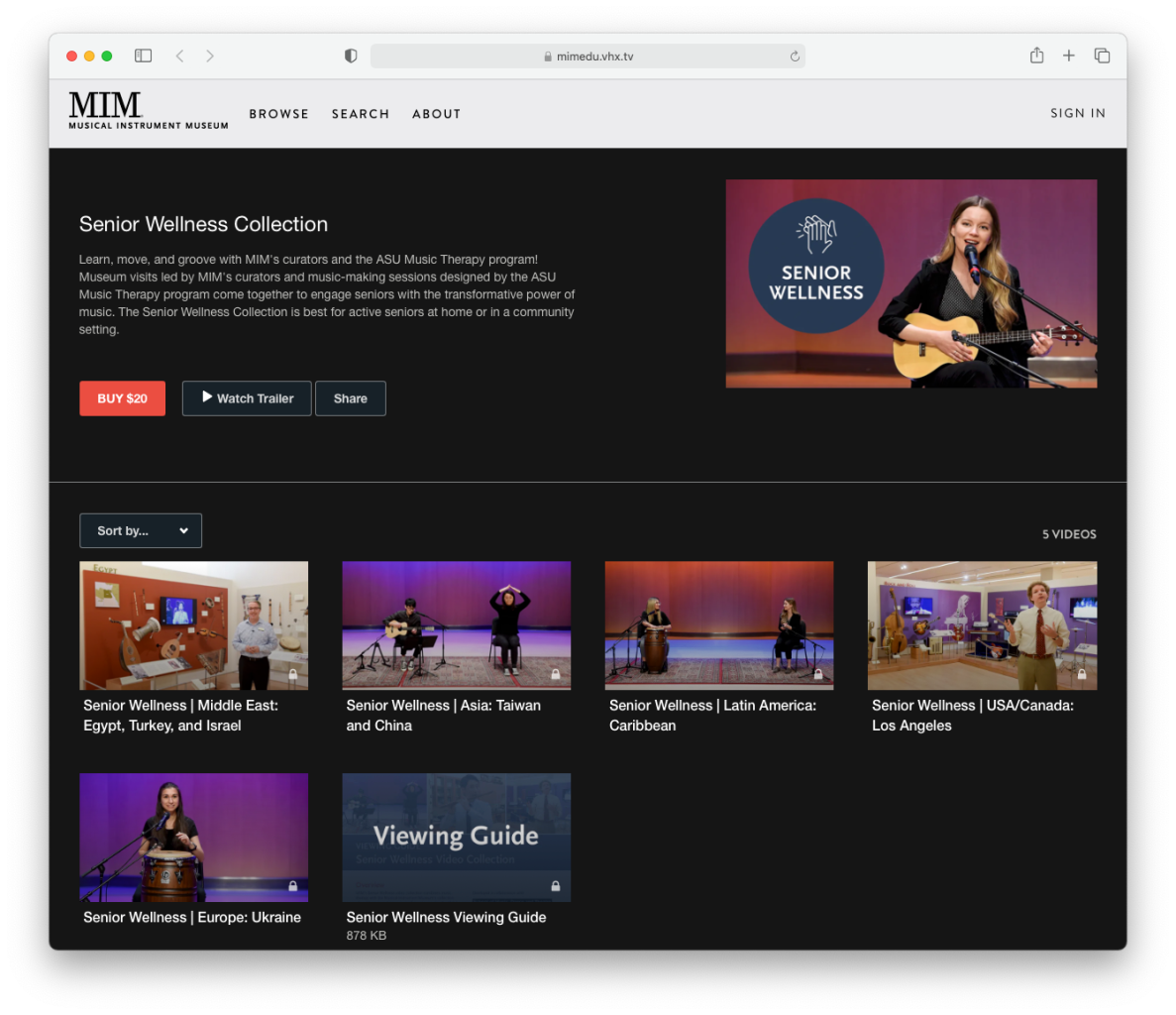

5. Finding a flexible distribution strategy

We wanted to offer a flexible way for seniors to access these materials, whether they are living at home, in semi-independent assisted living, or in memory care facilities. Hosting our content on Vimeo’s on-demand platform allowed an affordable and simple way for individuals to enjoy the videos, while we also offer the materials to institutions at a grant-subsidized group rate. Through the Vimeo platform, individuals or staff at facilities can download viewing guides that supplement the videos. This system is a recent innovation for MIM when it comes to content delivery, and so far we’ve seen a positive reception from participants as our mission is carried out into the community in a new way.

What we learned: Diversifying platforms was important in helping us achieve our goal of flexibility and accessibility. We took a chance on a new method and kept learning while we worked.

Concluding Thoughts

As these photos illustrate, the Senior Wellness program brought together a variety of perspectives from various MIM departments and our community partners. Diverse viewpoints, whether behind the camera or from MIM’s stage, made this project successful both as a reflection of MIM’s values and also as we ventured into new virtual territory for us.

For others looking to build asynchronous programming, here’s a summary of our key takeaways from the experience:

- Engage with the local community of experts.

- Keep an open mind about how to capture your institution’s experience virtually.

- Pre-planning and scripting deliver a stronger final product, especially for asynchronous formats.

- Work across departments and in collaborative teams.

- Get creative to meet audiences where and how they want to learn.

What’s next for the program? We’re currently working on extension activities that provide additional ways to engage with the culture of regions represented, whether through exploring more audio content with Spotify playlists, cooking the cuisine, or crafting an instrument. Soon, we hope to return to our full schedule of on-site senior programs in addition to the virtual offerings.

More information:

Watch the trailer for MIM’s virtual Senior Wellness collections

Find MIM on Facebook: Facebook.com/MIMphx

Twitter, YouTube, and Instagram: @MIMphx

Comments