In this series of posts, EdCom’s Trends Committee is taking a deeper look at emerging phenomena identified in the 2021 edition of TrendsWatch from the Center for the Future of Museums. In this post, they explore how museums sought to address the digital divide made deeper by the pandemic, and how ongoing commitment to accessibility and partnerships allowed educators to shift in new ways to support their regular audiences.

Whether you work at an art museum, history museum, science museum, or zoo, chances are you experienced the forced “digital awakening” examined in the 2021 edition of TrendsWatch. Throughout the pandemic, simply put, most institutions have either grown digitally or closed their doors.

For educators, this growth has come with some complications. Because we are predisposed to thinking about how to serve students, schools, and community members who are not adequately served by their local school systems and governments, we quickly saw the downside of transitioning to digital offerings: the impact of the digital divide.

The digital divide is the gap between people who have access to information and communication technology—including phones, personal computers, and the internet—and those who have little or no access to it, often because of their place of residence or demographics. This divide affects millions of people. A 2019 Pew Research Center report found that the limiting of information and access spans both rural areas (five million households) and urban areas (15.3 million households). During the pandemic, this became especially visible, as people adapted to the sudden loss of in-person gatherings and resources. We saw teenagers sitting alone in parking lots by closed school buildings trying to gain access to the school internet and engage with a community of learners steps away. We saw teachers and caregivers struggle to build online learning environments with platforms they had never used before. In other words, we saw how access both to digital tools and digital skills is essential for achieving digital equity.

Skip over related stories to continue reading articleAs museums charged into a world of digital offerings, many of us lived by a mantra: if our visitors could not come to us, we would go to them. But what about the visitors who did not have access to the internet, or even a cell phone? As we applaud ourselves for using technology to reach thousands, even millions, of people in new ways, we must also acknowledge who we left out and begin to plan a new world that gives access to all.

This piece examines what some museums did to bridge the digital divide and calls on you, the reader, to consider the role of museums in widening or shrinking it. How can our programs and offerings excel through the lenses of access, accessibility, and equity? How can museums play a vital role in supporting digital education to effect change? Finally, how can they ensure that they support digital infrastructures that bridge the digital divide, not widen it?

Creating Digital Access Through Partnerships

Many museum educators sought to bridge the digital divide during the pandemic by forming partnerships that bolstered digital access. At the California Academy of Sciences, for instance, educators worked closely with the local school district to address students’ needs during closures. One of the resulting projects involved partnering with a local broadcasting station. As Lindzy Bivings, Senior Manager of School and Community Partnerships at Cal Academy, explains, the museum had noted that families who did not have access to the internet usually had access to televisions. To reach these families, the museum produced short science videos for the station that included learning activities, animal highlights, and science-themed content for kindergarten through second-grade students. Staff made these videos without any additional budget, using their existing time and resources. In another project, to help families who could access the internet but experienced overloaded or unstable bandwidth, educators created asynchronous student activities with downloadable audio and text directions, which teachers could share easily through their online educational platforms.

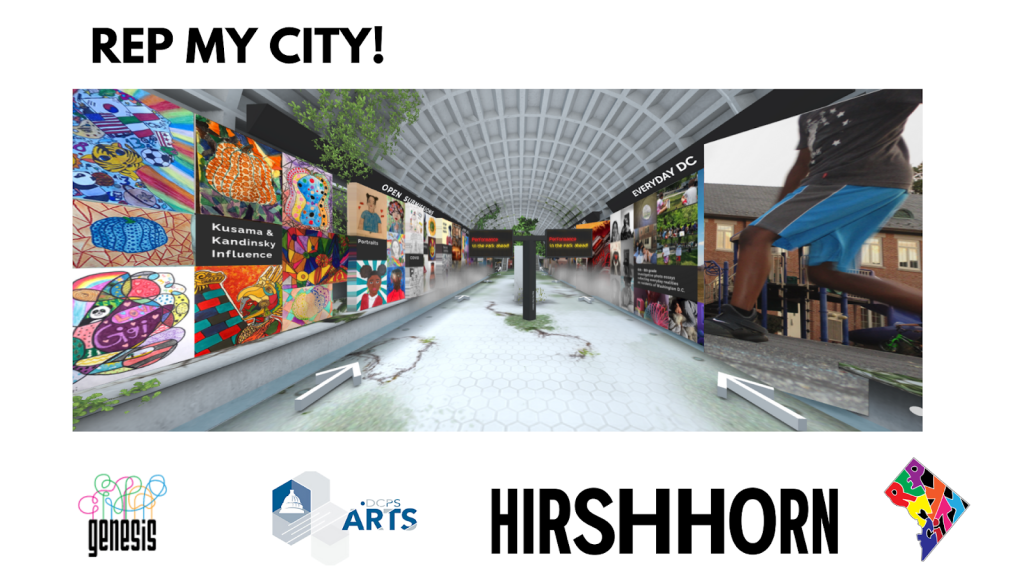

Additionally, Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden strengthened its school partnerships to provide training in digital skills. Tiffany McGettigan, Head of Education at Hirshhorn, explained that the museum’s ARTLAB, a digital art studio for local teen creators, hosted after-school drop-in programs and workshops with free access to art supplies, digital technologies, and one-on-one mentorship from artists. With its physical ARTLAB space closed, its educators partnered with District of Columbia Public Schools (DCPS) to produce the Emerging Artists program, a semester-long workshop series where teens created their own exhibitions with the support of artist mentors. In Spring 2021, Emerging Artists participants also helped implement Rep My City!, a virtual citywide art showcase for DCPS students. They worked with the Hirshhorn and Genesis, a STEAM education nonprofit, to develop the showcase’s concept and create their own virtual rooms. Rep My City! received 1118 submissions of 2D and 3D artwork and performances from 118 schools. Because the city provided laptops to students for virtual learning, most could access these programs.

The Wexner Center for the Arts also turned to community partnerships to create inclusive and collaborative online spaces. On February 27th and 28th, the museum co-hosted an audio program called “All Day Blackness: Black History and Black Futures” with Verge.fm, an online radio station. From the hours of noon to six p.m., Verge.fm broadcasted performances, music, and conversations exploring Blackness. Dionne Custer Edwards, Wexner Center’s Director of Learning & Public Practice, and Reg Zehner, Co-founder of Verge.fm, said online radio was the ideal venue for the program. Through radio, audiences had multiple entry points to the event: they could listen either on their computers or their phones, via Verge.fm’s app or the Wexner Center’s website. Moreover, after the event finished airing, they could find all content from “All Day Blackness” archived on Mixcloud.com, Verge.fm, and wexshumatecouncil.com.

Understanding Audience Needs

To develop and sustain digital engagement, you must know who your audience is and what they need. All of the people we interviewed for this piece talked about the importance of knowing (and understanding) one’s audience.

For instance, Custer Edwards and Zehner explained that they developed “All Day Blackness” by asking how they could care for local community needs. They landed on the idea to create a platform for young voices, because, as Zehner explained, “Artists are still not being afforded the same amount of respect, or pay, or even put in the forefront, even though a lot of people like to consume the work.” Thus, “All Day Blackness” was both a celebration of Blackness and a communal effort to care for community members and support young people’s ideas.

In the process of its digital transition, the Hirshhorn learned useful feedback about audience needs and applied these insights to future programming. McGettigan’s department learned that some Emerging Artists participants would not have been able to commute downtown to participate in the museum’s after-school programs. Also, some participants were simply more comfortable participating online, rather than in person. For that reason, the team hopes to adopt a hybrid structure for future Emerging Artists programs, with weekend sessions in ARTLAB’s physical space and weekday online after-school sessions.

The California Academy of Sciences also designed its virtual programming around audience needs, using rapid feedback during implementation to adjust as needed. Six weeks after schools adapted to online learning, the museum’s educators conducted empathy interviews with teachers and used these conversations to structure program design and identify potential issues, such as internet access and student engagement. Teachers shared that they wanted succinct, dynamic science lessons that engaged students online and offline, especially given students’ Zoom fatigue. Museum educators used this feedback to design a monthly science series that eventually attracted five hundred thousand attendees. Using teachers’ feedback, they built in opportunities for student engagement before the webinars, utilizing tools like Padlet, Mentimeter, and EdPuzzle, and they created offline activities students could perform outside, such as “sidewalk science.”

Building Longstanding and Reciprocal Relationships

To successfully meet your community’s needs, you need more than occasional moments of dialogue with them. You need ongoing conversations and collaborations that lead to genuine relationships.

This sort of relationship was key to the success of “All Day Blackness.” “A program like this is built out of a genuine, ongoing dialogue,” Custer Edwards said. “We needed to understand where each other was coming from.” In order to collaborate effectively, the Wexner Center and its local community needed to build a reciprocal relationship with trust at the center. Zehner agreed that partnerships should embody respect and exchange, citing the example that museums must engage and keep pace with artists’ current innovative digital practices to effectively support them. While institutional change may be more gradual than artistic change, Zehner said, “sometimes being too slow is too late.”

McGettigan also discussed how Hirshhorn’s ARTLAB serves as a place for community-building and collaboration. ARTLAB’s mentors and staff create an inclusive environment that celebrates teens’ intersectional identities and welcomes young creatives’ ideas. For example, the Hirshhorn has used ideas brainstormed by ARTLAB participants to stage other programs at the museum, like The Salon, an immersive installation that celebrated Black hair and hair salons.

A Framework for Closing the Digital Divide

Museum teams have spent the last year-plus building, creating, and thinking on their feet at top speed. They have learned how to remove the walls of our museums and invite the world in to learn. This innovation has caused a significant—and some would say long overdue—change in the museum field, and it has brought to the forefront some fantastic work.

However, it is easy in processes like these to get stuck in a cycle of creation, neglecting to reassess the practices and tools you use. This can undermine the impact of your programming in the long run, especially when it comes to questions of access. As FCC Chair Jessica Rosenworcel argues, broadband internet is no longer a luxury good in the twenty-first century, but a utility for full participation in life. The internet and other digital tools for accessing information have become a basic necessity. Museums should take this to heart as they go through their “digital awakening,” ensuring that all digital work centers access and equity.

Here are some tips for working toward that goal:

- Reexamine outreach tools. Even though we may have grown accustomed to using software like Zoom during the pandemic, we should remember to review, evaluate, and refresh our methods with a lens on bridging the digital divide for all members of our community. How can your existing platforms and software help you achieve your goals and ensure digital access?

- Enhance what you have. Examine preexisting equitable program models that have been a success for your museum. Then, ask how you can apply them to a digital setting. Don’t abandon a great program; when you can, modify it.

- Form digital access partnerships. Find partners who are reaching students, teachers, and adults in your community and supporting them with digital tools or access. Ask to partner with them to help deliver the rich and compelling digital content museums have to offer.

- Ask, don’t assume. Listen and work with community groups and families to find out what their needs are, then build programs to support those needs. Museums have been safe spaces for hundreds of years, and during the pandemic, our museums continued to serve the community as great providers of content and as sites of refuge and safety. Our sites can be great locations as third spaces for students to work on homework and access broadband internet.

I really appreciate how this post addresses digital equity in terms of access to museums and how organizations like the California Academy of Sciences sought to collaborate with schools in their district in order to reach students where they were.

In order to create equitable programming, more museum’s should seek co-creation with their communities, both during “lockdowns” and beyond. Forging and maintaining these strong connections can not only help the museum in the long run, but also act as a positive force for change and support system within the communities they serve.