The Brooklyn Children’s Museum is decolonizing its collection with the help of local teenagers.

This article originally appeared in the May/June 2022 issue of Museum magazine, a benefit of AAM membership.

You can’t use a Snapchat filter on taxidermy. The algorithm doesn’t recognize the glass eyes and animal faces. Our teenage collections interns at the Brooklyn Children’s Museum learned that the hard way, one of many lessons, from humorous to serious, that they absorbed as they helped the museum rethink its collection.

Brooklyn Children’s Museum (BCM) is the world’s first children’s museum, founded in 1899. Like most museums of its age, the collection was mostly acquired in the pre-internet days as a means to introduce Brooklynite children to other people and places. Objects brought to BCM, mostly by wealthy white donors, were a way to catalog the exotic “other” they saw on their overseas holidays. At times, visitors from our community did not see their own lives or experiences reflected in the objects on display. By 2016, our collection was ripe for reinterpretation and decolonization.

We have done this in two ways: through the Rapid Response Collecting Taskforce (RRCT) initiative of 2017–2019 and our current Teen Curators Program. Both programs, which have included between 10 and 20 teenage participants per semester, have focused on honest discussions based on the following core questions: How is history presented? Who makes the decisions about presentation and representation? Who holds the power?

RRCT grappled with the in-perpetuity nature and the history of the museum collection object, while the Teen Curators Program engages with more temporal questions about curatorial intuition and the power of community members temporarily loaning the museum objects for a show. The Teen Curators Program is about the present and extends the museum into the teens’ own lives and communities by empowering them to become their families’ own archivists. RRCT was about engaging with the collection and the history that’s already at the museum. For both programs, the end goal is decolonizing our collection and the practices that ground it.

Addressing Critical Questions

Launched in 2017, RRCT engaged our interns in rapid-response collecting, which is when curators and members of the collection department actively seek out objects they believe have immediate cultural value or are connected to an event or specific need for the collection. The program was born from a collaboration between our teen program, then overseen by artist and educator Oasa DuVerney, and the collection, which I manage.

This program was an organic response to the teens’ discussions about why a museum has objects and why it might value some over others. These critical questions, combined with our reading of a New York Times article about the National Museum of African American History and Culture’s own rapid-response collecting initiatives, led to the creation of RRCT.

Teens in the program were empowered to select objects for BCM’s collection that would be preserved in perpetuity and to add narratives they deemed important. They identified broad themes that mattered to them and those they found to be underrepresented or nonexistent in the collection, such as criminal justice, immigration, LGBTQ+ rights, racism, gentrification, propaganda/fake news, voting rights, and feminism.

“We went into the community and collected objects with stories that we felt not only held personal importance but also political, social, and economic importance in which to accession into BCM’s collection to be preserved and remembered for years to come,” says former RRCT intern Clara Youens, now a student at SUNY Stony Brook.

Teens would bring in an object that represented something important to them. Following the points laid out in the manifesto the teens created (see “Words to Collect By” sidebar below), the group would decide if the object should be accessioned into the collection. Once the object had been thoroughly discussed and voted on, the teen who brought it in would assign it an accession number and partner with someone else to write down the object’s provenance and registrarial information. This information was added to the object database and the collection’s historical record.

Teens sometimes reacted to events they saw in the news. For instance, in 2018 they organized museum-wide participation in the NYC March for Our Lives protest related to gun violence. They collected participants’ signs and ephemera and interviewed them for the accessioning information. They also accessioned the suit then-City Council Member Jumaane D. Williams wore when he was arrested for peacefully protesting the deportation of immigration lawyer Ravi Ragbir in 2018.

“It was extremely humbling to be asked to share these items with Brooklyn Children’s Museum and with the young people of the Brooklyn community,” said Williams, who is now New York City’s public advocate, in 2018. “This was never my intention, but it’s incredibly gratifying to think that the actions that I and other protesters took could educate and inspire future leaders to stand up for what they know to be right in the face of adversity.”

Through RRCT, our teen interns learned curation and collection skills as they documented history in real time. Most important, they participated in remodeling an institutional power structure. Their work will make our collection a more relevant and inclusive resource, not only today, but for future generations of children and families.

“Being part of RRCT wasn’t just my first exposure to collections work, it was my first major experience working at a museum,” says former RRCT teen intern Joshua N. Miller, who went on to graduate from Goucher College and intern at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. “I’d always been passionate about history, but being entrusted to collect objects that speak about the experience of young people around Brooklyn was an immense show of faith. It inspired me to go above and beyond the task then and motivates me to provide a similar opportunity for future historians now.”

Developing a Curatorial Voice

In the hot summer months of 2021, BCM’s Teen Program Coordinator Omololu Babatunde and I launched the Teen Curators Program. This nine-week program focuses on personal and community narratives as interns record their own oral histories, temporarily loan personal objects to the exhibitions they curate, and develop their own curatorial voices.

The program has two core pedagogical parts. The first offers a historical foundation about how museums came into being. Workshop lessons cover museum terminology and the different roles within a museum, and we invite members of our staff to talk about how they approach their jobs. From the start, we ground the conversation in a colonial/decolonization framework.

We use BCM as a case study for larger conversations about collecting—what is meaningful enough to be preserved and why, the history of museums, what it means to tell stories with objects, and the inherent power dynamics embedded in managing a collection.

For example, in one lesson teens investigate objects from a donor who traveled the world as a Christian missionary, amassing a substantial object collection of mainly West African and South Asian instruments, adornments, textiles, masks, and everyday objects and some 10,000 slide images. In 1984 he donated everything to BCM, and many of these items still have their original donor tags attached, which show how this donor viewed these cultures and their material objects as “other.” No matter the culture, the objects were labeled “Primitive, Exotic”—an explicitly white, Western, colonial view of the world.

When our teens physically explore these objects and their tags, they start to understand larger issues in an accessible and tangible way. They reach their own conclusions about the individual objects and the donor’s intention. They can then consider the life of the object, from its place of origin and the hands that created it to its current home at BCM. We use our collection for hands-on education, exposing what is typically made invisible or edited.

Part two of the curriculum can be summarized as “Where do we go from here?” After the foundational structure of the first part of the program, the teens, through an approach grounded in socio-emotional reflection and their own intuition, create art. In doing so, they position their voices at the center of what it means to create. They decide their own narratives and, most important, how those narratives are shared with others. As opposed to RRCT’s “objects in perpetuity” that were accessioned into BCM’s collection, the Teen Curator Program emphasizes the temporality of the teens’ own experiences. They narrate and analyze what’s happening now rather than preserve an image to look back on.

In this part of the curriculum, the teens learn how to conduct oral histories by interviewing a neighbor or family member for at least 20 minutes. While this prompt initially elicits groans, many teens find this active collection work empowering. The interviewees—immigrants, younger siblings, grandparents—feel validated by the conversations, not only because they are conducted in the name of BCM’s collection but also because they receive records of their conversations.

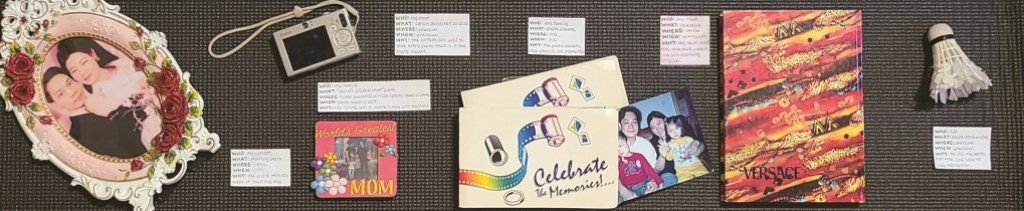

We also give the teens a chance to temporarily lend their own to the rotating gallery cases in an exhibit called “BK Voices.” The teens write their own object interpretation, which allows them to hone their curatorial voices while maintaining ownership of their objects and their narratives. They show only what they want to show as opposed to what the museum or the curator wants to show.

Finally, to bring our goal of decolonization beyond the museum’s walls, teens transform words and phrases from the oral recordings they collect into flyers, which they post around the neighborhood on lampposts, at bus stops, and in train stations. This allows them to influence their own communities and serves as a call and response between the museum and the community.

We have measured the success of both programs through their retention rates, each of which reached 95 percent. We also hold one-on-one check-ins with the teens to ask them about how they’re feeling both in the program and generally in their lives, emphasizing that their time at BCM is meant to be socio-emotionally supportive. For the Teen Curators Program, an outside evaluator surveys the teens at the end of each semester, noting any constructive criticism that we can use to improve the next semester’s program. For example, we now focus less on article and text readings and more on hands-on work.

Statistics aside, our strongest measure of success comes from our direct dialogue with the teens. If they tell us that our programs have changed their lives in any way, then we believe they are successful. One fall semester intern, Mathew, age 16, provided this simple feedback: “It has changed how I see.”

Eye on the Future

Over the past few years, our staff has learned a great deal both about how to begin decolonizing a collection and how to bring teenagers directly into our work. Here are a few of the highlights.

- BCM’s collection should be educational rather than preservation focused. Our primary goal has always been to serve our community, which is why including teens in the decolonization process has been so successful. A preservation-oriented collection can still take on this work if staff trusts young people to be mature enough to understand the generational implications of collections work, to see themselves as part of this larger process, and to interact with collection spaces with respect and dignity, as a museum professional would.

- The registrarial processes, and even the paperwork that is the foundation for a museum’s collection, are incredibly important. These things should be transparent and can be woven into a museum’s entire educational approach and outlook. When your audience understands how and why you operate the way you do, their feedback can help change how you view the collection.

- What is important to teens is important to the community. Ask your teens what’s important to them. Are their answers currently represented in your collection? Whether they are or aren’t, this conversation starter can inform why and what you can do to ensure the teens, and by extension the rest of your community, are represented in your collection.

Words to Collect By

The first cohort of Rapid Response Collecting Taskforce (RRCT) teens created the following manifesto, which functioned as collection management policy for all RRCT work.

We are the Rapid Response Collecting Taskforce (RRCT). RRCT is a collective Taskforce by and for the youth. We will venture into our community, engage within it and collect objects we deem important.

We have the power to make these objects permanent artifacts within the BCM collection: not only will these objects remain at BCM, but our impact will remain for future generations to see.

We will enhance people’s lives with knowledge and access.

Our presence does not signify the complete solution to this institution’s biases; more than documenting what present society has deemed important to see, we will decolonize what is taught and learned and shed light on social justice issues that go with and without proper media coverage.

We believe in placing people before objects. While objects are crucial to represent the community and stories of it, above all, we aim to preserve the personal narratives that went into creating said objects. Not only will the objects be researched thoroughly, but the human perspective that sparked their origins will also be recorded.

We demand time to practice our skills of analysis.

We demand funding and visibility for RRCT.

We demand to hold the people in power accountable for their biases.

We have the power.

Comments