The news about climate change, the environment, and the state of our planet is frightening and discouraging. In the face of it all, how do we create hope? According to noted conservation psychologist John Fraser, the answer is by focusing on solutions and actions. Hope, Fraser says, “is a targeted way of seeing the future and taking steps to get to that future.”

For that reason, at Discovery Museum, a children’s museum in Acton, Massachusetts, we have begun to emphasize the actions we can take as organization to directly impact climate change. I share our experience in the hope that any insights it yields will help us all take more action and inspire our visitors to do the same.

Building on a Foundation of Environmental Focus

Discovery Museum has a strong focus on science and nature, with 4.5 acres of accessible, outdoor exhibit space adjacent to 180 acres of town-owned wooded trails that we program. Encouraging appreciation of nature and operating sustainably have long been important goals for us. Over the last decade, our environmental work has focused on the goal of connecting kids with nature, both to raise awareness and promote the physical and mental health benefits of outdoor play.

We have also taken steps to advocate publicly for the values of sustainability and stewardship, including signing the We Are Still In (WASI) pledge, a joint declaration of support for climate action signed by more than 3,900 CEOs, mayors, governors, tribal leaders, college presidents, faith leaders, health care executives, and others; joining America Is All In, a coalition to develop a national climate strategy; supporting the Town of Acton in declaring a climate emergency; becoming a member of the Acton Climate Coalition; and presenting programs addressing environmental topics through our Discovery Museum Speaker Series.

Walking the Talk

Having laid this groundwork, we have increasingly wrestled with how to take concrete steps to be visibly and demonstrably sustainable in our own operations as a key strategy for inspiring the next generation of environmental stewards. The goal is to motivate families to adopt more sustainable viewpoints and practices at home and support environmentally sound public policy. We wanted to more visibly “walk the talk” as a critical element of our educational approach.

Recognizing this, we knew we needed a plan. One of the first things we decided to do was look for advice and guidance. We had lots of questions about scope, level of detail, what kinds of goals we should have, and even how we should define “sustainability” for our organization. Luckily, we had some prior experience working with Sarah Sutton, who helps places like ours through her organization Environment & Culture Partners. She provided positive feedback on our goals, an invitation to join with other cultural institutions as part of We Are Still In, and some great links to useful resources.

One especially useful resource for us was the WASI list of commitments. Sarah noted that others had used this list as a framework for creating their own sustainability plans. A white paper from Museums Australia had a very similar list. Based on a review of these examples, it made sense for us to follow their approach.

Our framework was built around a set of “commitments”:

- Commit to increased use of renewable power

- Commit to understand and reduce greenhouse gas emissions

- Commit to reduce materials consumption and waste

- Commit to reduce the impact of transportation

- Commit to reduce water usage

- Be publicly committed to sustainability

- Commit to education and communication

- Integrate climate change into portfolio analyses and decision making

From there, we moved straight into researching and producing a plan focused on these action steps. Key to this was establishing the museum’s baseline environmental impact, which we did with the tremendous support of a skilled intern who self-described as a “sustainability geek.” With her help, we found answers to a range of questions: How much energy do we use, and in what ways? What level of greenhouse gas emissions do we produce? What does our water consumption look like? How many miles are we driving? How many deliveries do we get? How much waste do we generate? What are our cleaning supplies and the materials in our exhibits and programs made of? In what ways do we talk about the environment? And many more.

For some of these questions, the data was readily available. Our utility company is very good about keeping track of our electricity, oil, and natural gas usage, for instance. Our water company was a bit trickier, as they do a poor job in regularly reading the meter. In some areas, no real good data source existed. For example, the waste collector empties the dumpster on a regular schedule, whether it is full or half empty.

Turning Our Vision into Reality

There are a number of models that can estimate greenhouse gas emissions based on energy usage or miles driven; our goal was to find one that was relatively simple to use and easily available to us. The model used by our intern produced easy-to-understand visual representations of our greenhouse gas sources. This was useful for discussing our action steps with staff and the board, as it made the priorities much clearer.

One interesting data point stems from our being a suburban museum with effectively no public transportation option. Everyone (mostly) drives here, so we used visitor zip code data to come to a pretty good estimate of miles driven by our visitors. As it turns out, this is the single biggest source of greenhouse gas emissions for the museum, and as you would expect, not the easiest to address.

We recognized that our data collection efforts were not perfect, but we decided rather than devote lots of time and resources to get perfect data, we would create objectives for filling in the blanks later. Even though our measures of progress would be less than precise, we were moving forward.

Our analysis of this imperfect data became the platform for the development of concrete goals and actions, and what we hoped were reasonable timeframes for accomplishing them. We also committed early on to implementing our plan transparently and allowing for flexibility as we make progress and learn along the way.

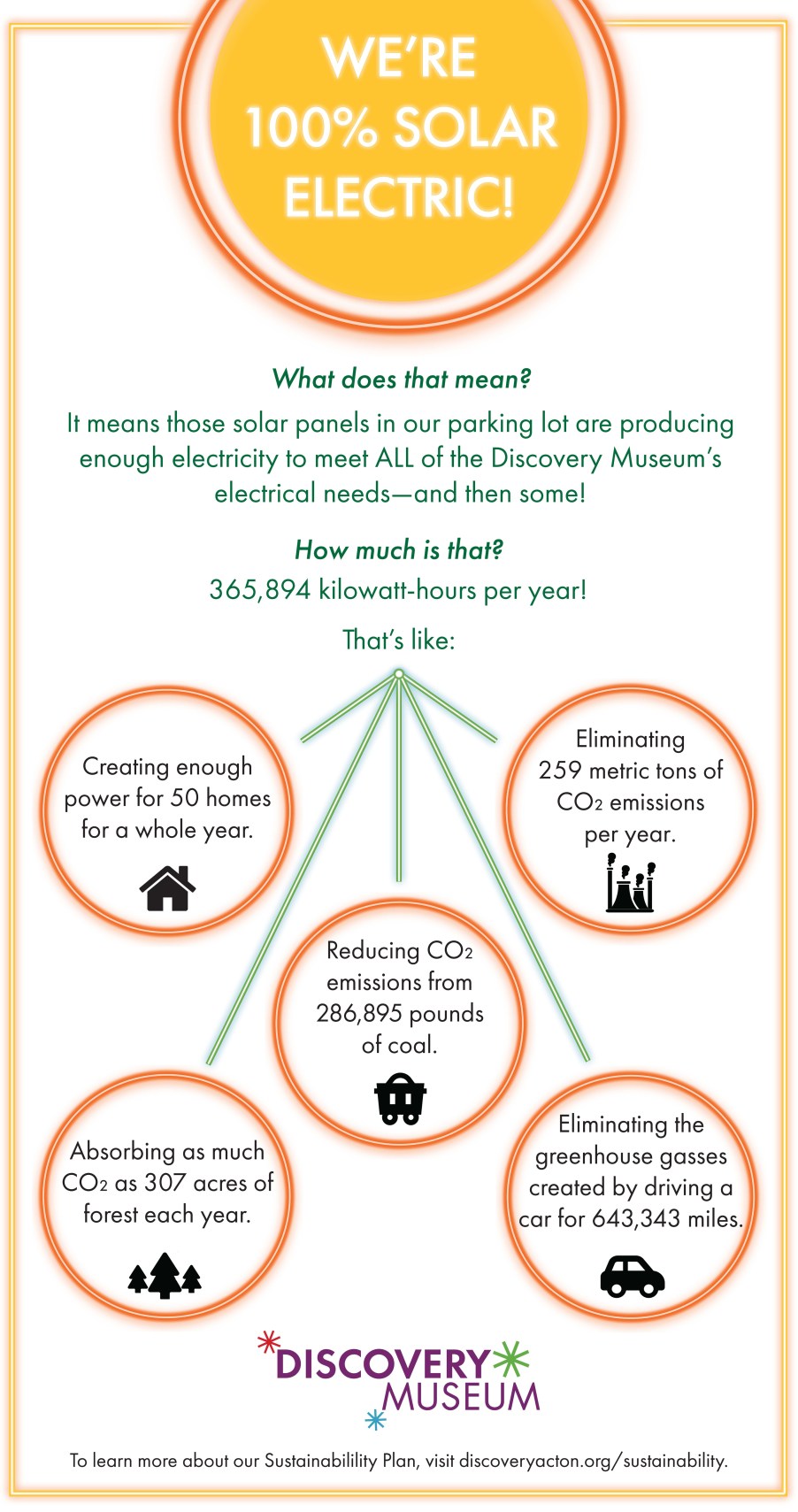

The most visible part of the plan is our project, completed in mid-2022, to produce solar electricity onsite to meet 100 percent of our campus energy needs—and then some. The plan also outlines our approach to reducing greenhouse gas emissions and becoming carbon neutral; reducing water usage; minimizing waste generation; investing sustainably; and advocating for climate action. All of this will support an environmental education effort that will connect kids and families with nature, help them learn in partnership with the natural world, and inspire them to advocate for sustainability—all in the fun, hands-on Discovery Museum way. The final plan includes twenty-nine action steps, spanning all areas of museum operations, to be taken over the next several years. These actions include discrete tasks such as replacing pavement with permeable surfaces and redirecting stormwater to groundwater recharge. The plan also outlines goals for ongoing action, such as investing sustainably, building community partnerships to advance our environmental work, and advocating publicly for our values.

A Commitment to Flexibility and Progress

With our plan developed, we are now in the process of implementing it. We have created a Sustainability Plan Team made up of staff members throughout the museum who have primary responsibilities for one or more of the action steps articulated in the plan. The team meets monthly to review progress on each of the steps, share ideas or concerns in moving steps forward, and identify new or modified actions that we might take. In this way we have peer support and peer accountability for the plan, making sustainability more of an organizational norm.

The Sustainability Plan Team holds regular discussions on our progress, which helps to address the built-in imperfections of the plan itself. The team has become comfortable with the idea that we are both implementing the plan and improving it at the same time. For certain action steps, better ideas have emerged from our work together.

A good example of this centers on our ideas about visitor vehicle emissions. The original plan called for the museum to implement a system of visitor-purchased carbon offsets as a means of mitigating the emissions, not eliminating them. It anticipated both a mandatory approach and a significant visitor education component. In discussing this strategy, however, the team realized that the logistics of promoting, educating about, and collecting offsets would be too challenging to realize at once. So we decided to begin with a specific subset of our audience: members, staff, and volunteers.

Due to a lack of nearby transit options, we knew the carbon footprint of travel to and from the museum would be one of the biggest impediments to our objective of carbon neutrality. So, we had some conversations within our industry, and the Carbon Neutral Visiting Initiative (CNVI) was born. CNVI works with museums and other cultural institutions to understand, measure and offset carbon emissions and educate visitors about climate change. Working with CNVI, we assessed our carbon footprint and set up a mechanism to fund offsets for staff and member travel.

We calculated the average of the total number of miles our member families traveled to and from the museum in 2019. Then, CNVI used the Greenhouse Gas Protocol and other related carbon emissions calculation standards to estimate the amount of carbon emissions from that travel and the associated cost to purchase carbon offsets to mitigate those emissions. Beginning June 1, an opt-out one-dollar annual offset fee was applied to all new and renewed memberships; it has a greater than 99 percent participation rate. We similarly calculated commute and business travel for our staff and volunteers, and the museum funds offsets for that. We will look expand the program to cover all museum visitors next year.

Financially Sound Solar

Once you decide that solar electricity is the right thing for your organization, the question quickly turns to: Does it make financial sense? In Discovery Museum’s case, we were pleasantly surprised to find out that the answer was yes.

We started with a very simple model in mind: We would fundraise for the cost of installation and use the annual electricity savings to support our environmental education programs. Thus, we would describe the investment in solar as an endowment of the programs. This idea made some sense pre-pandemic, but quickly looked silly in the face of needing to raise funds just to stay open. That led us to scrutinize the economics in much more detail.

We quickly identified several companies that specialize in working with nonprofits on solar projects and chose to work with Boston-based Resonant Energy. Resonant was able to show us a model of solar financing that involved “selling” the federal tax credits we would get (obviously, we would not be able to use them directly), estimating our energy savings, selling excess electricity to other nonprofits at a discount, and maximizing other incentives (in our case, solar incentives offered by the state of Massachusetts). The access to the federal credits is a bit complicated and you’ll want a lawyer for that work, but it results in a 12 to 15 percent “savings” right off the top. Resonant was able to show a twenty-five-year financial model that accounts for decreased production over time (we were surprised to learn that panels wear out), operating costs such as maintenance, changes in electricity rates, and so forth. To support our analysis, we put together a Solar Task Force of board and non-board experts that reviewed the modeling and evaluated our options.

The Solar Task Force was able to recommend to our board that the museum finance this project. With low interest rates and a good bank, we put in place a loan that should be paid back in about eleven to twelve years. The projected cash flow is positive in year one, thus actually meeting one of our original goals of supporting programs using the sun!

Getting the project built and operating can be complex, and a lot depends on how your panels will be sited and installed, the state in which you are located, and the utility that serves your museum. In our case, we installed the panels on canopies over our parking lot rather than a roof. The project involved site work, canopy construction, and solar panel installation, and thus multiple contractors and lots of coordination. Having an overall project manager was important to keeping that all moving along and managing any potential impact on our daily operations.

Understanding how your project relates to the electric grid is another important variable. In our case, we wanted the reliability and flexibility we would get by staying connected to the grid (others may choose to install batteries and retain all the produced power on site.) Thus all the electricity we produce goes into the grid and that input is metered. The electricity we use comes from the grid and that is measured as well. (Since we continue to get our power in exactly the same manner, there is effectively no “transition.” The “switch” that gets flipped is the electricity flowing from our array into the grid.) The difference is “net metered,” resulting in either credits to us or money we pay to the utility. In our case, we’ve sized the system such that we will produce credits. In a complex manner, we are selling those solar energy credits to other nonprofits so that they can power their operations with renewable energy; we are selling at a below-market rate to recognize their non-profit status. For the organizations buying the credits, they simply see them on their utility bill as discounts applied against their usage. Again, do not attempt this without a lot of locally knowledgeable help, as the rules vary by state.

So, in the end, we are powered by the sun, powering others as well, and have created an incredible, visible commitment to inspiring others to embrace a more sustainable path.

A version of this article originally appeared in Hand to Hand, the magazine of the Association of Children’s Museums.

How could we be a part of your organization