Lessons from the Center for Design and Material Culture at the University of Wisconsin–Madison.

This article originally appeared in Museum magazine’s May/June 2023 issue, a benefit of AAM membership.

For more than 50 years, the Helen Louise Allen Textile Collection (HLATC) has been a destination for those passionate about global textile traditions. And for the past five years, the collection has been the foundation of a curriculum that seeks to help those visitors understand the difference between cultural appropriation and cultural appreciation.

The collection is home to more than 13,000 textiles from around the world, ranging from ancient to contemporary materials, and is located within the interdisciplinary Center for Design and Material Culture (CDMC) at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. The collection serves a wide range of researchers and community members as well as scores of UW–Madison courses. Classes as diverse as history, financial coaching, interior architecture, and weaving find value in specially curated and facilitated object pulls as well as the changing exhibitions in the Lynn Mecklenburg Textile Gallery.

Many of these students, especially those in art and design-related majors, turn to our collection for “design inspiration.” While students have likely learned how to responsibly quote and cite written materials, they do not necessarily know how to navigate the power dynamics inherent to the study of diverse cultural materials. Indeed, the CDMC staff realized that students lacked a framework for engaging with such materials.

In an effort to support these students and faculty, the CDMC started what has become the “From Cultural Appropriation to Cultural Appreciation” curriculum in the 2018–2019 academic year. Over several years of iteration, pilots, and initial evaluation, hundreds of participants have experienced the curriculum—primarily through invited sessions within university classes and special workshops for community groups and professional colleagues. We continue to hone the curriculum through evaluation and hope to share a finalized program with diverse community audiences within the next year.

Learning Goals

Our cultural appropriation curriculum offers collection-based case studies in which participants practice engaging with the three key themes: ownership, power, and impact. (See the “Three Key Curriculum Themes” sidebar on p. 50 for definitions of these terms.)

The team leading this project is purposefully diverse, composed of Indigenous and non-Indigenous collaborators as well as UW faculty, staff, and graduate students. This work has been generously supported by the Equity and Justice Network and the Indigenous EcoWell Initiative, which, like the team, are based in the School of Human Ecology at UW–Madison. The Indigenous EcoWell faculty work focuses on the intersections of Indigenous cultures, health, and language in collaboration with campus partners, WI First Nations, UW–Madison students, and the community.

We offer this curriculum as a teaching resource that we hope other institutions will adapt and use in similar ways with their own collections and audiences. The same issues we encounter when we engage with design students are important for curators, collection managers, designers, and other museum professionals to wrestle with—especially because museums often invite community engagement with the collections they steward. As visitors potentially look to our collection for design inspiration, we want to facilitate meaningful, respectful, and transparent interactions with the objects we care for and the cultures and communities from which they originate.

At the most basic level, cultural appropriation is the act of using or taking a cultural element from one cultural context and (mis)using it in another. But it can get complicated quickly: borrowing, exchanging, and reworking ideas, technologies, and art forms are central to creative work. So when, how, and why does this borrowing become a problem? In the curriculum, we explore strategies participants can use to identify where appropriation might occur and how to avoid it.

The brightly colored pair of HLATC objects at left has been a powerful way to invite participants into this work. One is a mola (blouse) made around 1930 and worn by Guna women of Guna Yala, Panama. The other is printed, quilting fabric yardage manufactured in 1977 by Pago, Inc., a New York company. The curriculum invites participants to look and wonder: What is similar about these two objects? What is different? What questions arise as you are looking at them or touching them? What other information would you like to know? Did seeing these two objects together impact how you viewed them? Why or why not? Grounded in participants’ material observations of and questions about this object pairing, we can talk about what cultural appropriation can mean.

After time for structured close looking, comparison, and discussion, we offer more context on our object pairing. The ability to make an outstanding mola is a source of pride and income among Guna women. Panama even protected this design in the country through a law passed in 2000 called “Special System for the Collective Intellectual Property Rights of Indigenous Peoples.” However, as molas have become more popular with tourists and international art collectors, the market has been flooded with imitation mola panels and other knockoff mola designs for home decor fabrics, bags, and towels for sale outside of Panama.

This pairing purposely invites participants to engage both as designers and as potential consumers. We discuss ownership of these traditional designs. We reflect on the power imbalances between Guna women and those who might buy or produce these designs abroad. Finally, we consider the impact of creating and selling this printed fabric.

Since our collection objects cannot leave our storage without loan paperwork, we have created a traveling collection of mola and imitation-mola quilting fabric so that off-site groups can participate in the hands-on, material lessons of this work. We hope other institutions will use this object pairing as an example they can adapt based on their own collections and audiences.

Once participants have more confidence with key terms and questions, we add more nuanced pairings. A range of “paisleys” from global contexts and knitting patterns along with the historic objects that inspired them or a kimono alongside a 1920s dress encourage conversation and meaningful engagement with our key concepts. Our goal is not to teach a single, static definition of cultural appropriation, but to equip participants with terms and questions about what it means to appropriate as opposed to appreciate diverse cultural designs.

We also make clear that sometimes the answer is not to borrow at all. How might we make space for and support artists and designers to create new works based on their own cultural heritage? We encourage our participants to learn from artists whose work is not only relevant to the topic of cultural appreciation but also centers the voices of Indigenous people and histories.

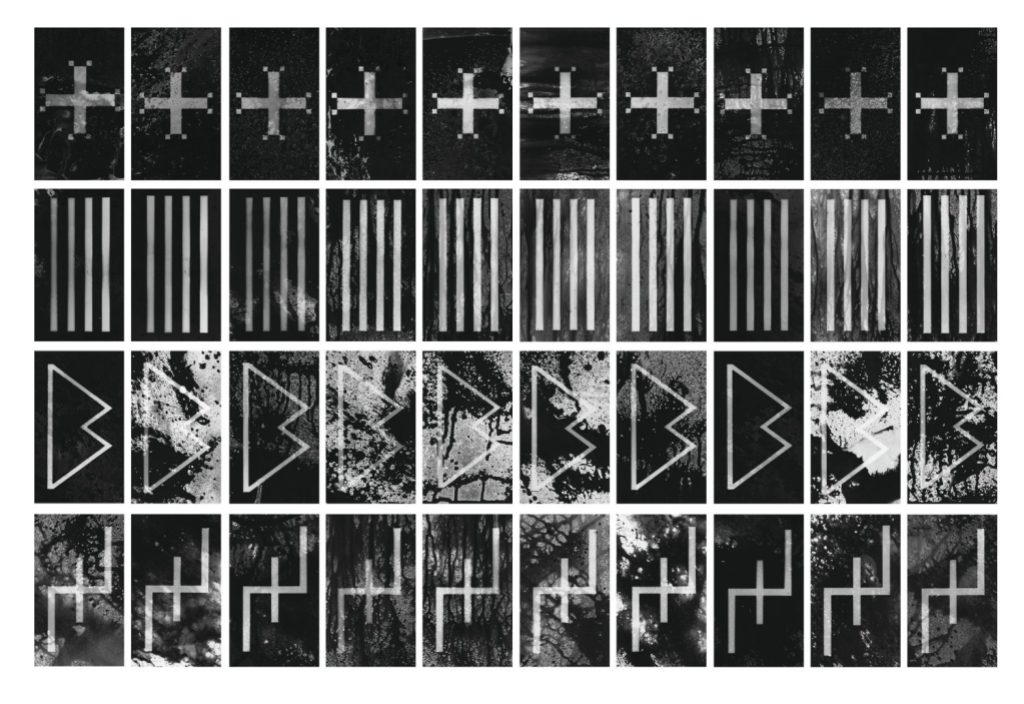

For example, our collaborator and photographer Dakota Mace (Diné) is one of many Indigenous artists creating transformative art grounded in cultural heritage. Her project Sǫʼ Baa Hane’ (Story of the Stars)” focuses on sharing her family and culture’s oral traditions through photography and design. By focusing on first-person interpretation and the work of specific artists, we offer concrete ways to appreciate and center the voices of Indigenous makers.

We also discuss collaboration and what mutually beneficial collaboration looks like and makes possible. These conversations aim to empower participants to discuss potentially uncomfortable concepts so that they can engage with diverse cultural materials more thoughtfully.

Evaluating the Results

In evaluating these workshops, we centered the work of Indigenous artists, scholars, professionals, and community members to better understand past and current contexts that shape our curriculum development. Professor Carolee Dodge Francis (Oneida Nation of Wisconsin), an Indigenous professor, scholar, and evaluator, and Joseph Jean, M.P.H., also an Indigenous scholar (Diné) and Ph.D. student, have been instrumental in advising the team and implementing evaluation tools. An Indigenous evaluation framework for the pilot curriculum highlights “being a people of a place, recognizing gifts, honoring family and community, and respecting sovereignty,” as defined in the 2014 book Continuing the Journey to Reposition Culture and Cultural Context in Evaluation Theory and Practice.

Thus far, they have created a pre- and post-workshop, five-question, web-based survey instrument to provide initial pilot data. UW–Madison students, community members, and participants from a regional conference have taken the evaluation, and the data shows some promising results. The number of respondents who knew the general definition of cultural appreciation increased by 25 percent post-workshop, and there was a 22 percent increase in the number of respondents who could identify the critical concepts that distinguish cultural appropriation from cultural appreciation, potentially demonstrating a deeper understanding of the topic.

The evaluation and results have sparked productive dialogue among the coauthors developing curriculum modules and among their Indigenous and non-Indigenous community partners. We plan to develop a mixed-methods evaluation tool that will offer further insights about curriculum participants’ knowledge patterns. The goal is to provide an evaluation toolkit, along with the broader curriculum, that is scalable and adaptable for other institutions.

This country has a long and painful history of erasure and cultural appropriation with respect to Indigenous people. Unfortunately, in late 2022 a community member with whom the Center for Design and Material Culture had partnered was alleged to have misrepresented their identity and engaged in a range of disingenuous actions, all of which is antithetical to our curriculum. Experiences like this are still too common, and institutions need to talk openly and humbly about cultural appropriation.

Working together, we can engage in responsible collaboration, research, and cultural appreciation. We hope to empower designers, design students, museum visitors, museum staff, and community members with the tools they need to make sense of this complex issue.

Three Key Curriculum Themes

Ownership: A design or object may be the property of an individual or cultural group.

Power: Cultural appropriation almost always happens in situations where there is a power imbalance between stakeholders.

Impact vs. Intent: Good intentions do not preclude harm. Cultural appropriation usually occurs unintentionally, but it can still be harmful, especially if amplified by issues of ownership and power.

Resources

“Think Before You Appropriate,” Intellectual Property Issues in Cultural Heritage (IPinCH), 2008–2016

sfu.ca/ipinch/

Stafford Hood, Rodney Hopson, and Henry Frierson (eds.), Continuing the Journey to Reposition Culture and Cultural Context in Evaluation Theory and Practice, 2014

Susan Scafidi, Who Owns Culture? Appropriation and Authenticity in American Law, 2005

James O. Young and Conrad G. Brunk (eds.), The Ethics of Cultural Appropriation, 2012

Comments