This is a recorded session from the 2023 AAM Annual Meeting & MuseumExpo. Before the field evaluates community impact, it must address an elephant in the room: the implicit (and sometimes explicit) binary between “visitors” and “community.” Is every visitor a member of a museum’s community? This panel will explore ways that museums are defining and redefining their communities, offering practical approaches, frameworks, and conversation starters for your own.

Transcript

Holly Shen:

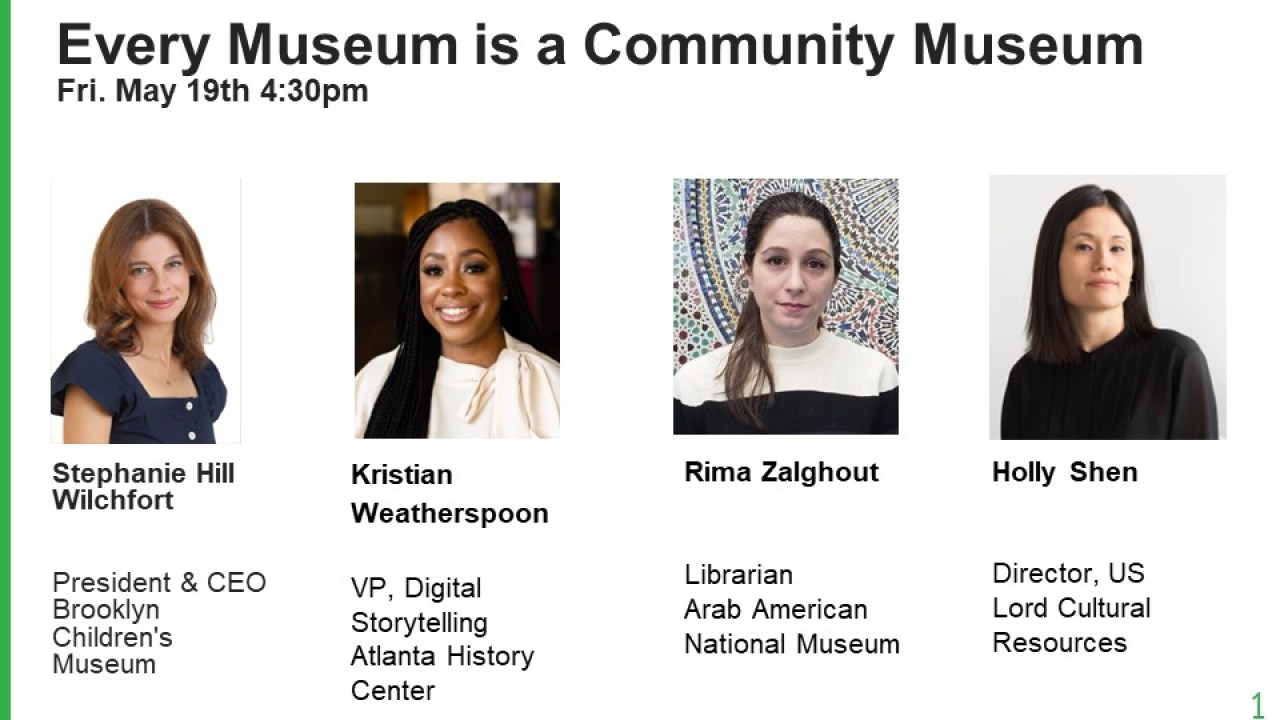

Welcome to the panel discussion, Every Museum is a Community Museum. My name is Holly Shen. I am a director in the US Office of Lord Cultural Resources, the global practice leader in cultural sector planning. And before I introduce our panelists and the discussion today, I wanted to just do a brief land acknowledgement. I’m based in California and Lord has an office in Long Beach. So I’m going to read that acknowledgement. That’s the one that I’m used to. Lord’s Long Beach office is located on the land of the Tongva Gabrieleño Nations and the Acjachemen Juaneño Nations who live and continue to live there. And I encourage all of you to acknowledge the folks who have come before you, wherever you may sit.

This panel was organized by Stephanie Hill Wilchfort, who is here to my left. So I want to thank her for organizing such a relevant and prescient topic in museums. And Stephanie is the president and CEO of Brooklyn Children’s Museum, which is located in Crown Heights, Brooklyn. And prior to joining that, she was the vice president for development at the Tenement Museum in Lower East Side and held a range of other positions in education and advancement in the museum sector. And joining Stephanie will be Kristian Weatherspoon, who is the vice President for digital storytelling at the Atlanta History Center. And Kristian is a award-winning digital journalist and storyteller with 10 plus years experience producing hybrid, digital, and social media projects and communications.

And finally, we have Rima Zalghout Librarian at Arab American National Museum in Detroit, Michigan, where she oversees the Russell J. Ebeid Library and Resource Center and organizes and facilitates the Arab American Book Award, an annual literary award that supports and celebrates the written word of Arab Americans. And myself, Holly. I will be moderating the discussion. As I mentioned, I work for Lord Cultural Resources. I’ve been there for a little less than a year. Prior to that, most of my experience has been in cultural institutions and museums. I was the deputy director at San Jose Museum of Art most recently and before that was at Brooklyn Academy of Music where I oversaw the, was the director and curator of the visual arts program there. So this topic of every museum is a community museum, is one that has come up over and over in my work in cultural institutions.

And really we want to focus the discussion today around this often fraught conversation, what do we mean when we say community in the context of cultural planning or museum sector work? Many institutions tend to shy away from self-identifying as a community museum, but on the other hand, they often embrace the terms community outreach or community engagement. And so the questions that we are posing today are really, is every visitor a member of a museum’s community? Is every museum a community museum? And what are the different frameworks or rubrics that we can use to understand what community means in this context? And what are some conversation starters for some of the practitioners in the room who might be grappling with these same questions in your work? So before I, we’re going to let each panelist give a brief kind of introduction to their role in their organization and what they do.

And then we’ll have a series of questions and then we’ll open it up to the audience for questions. But before I turn it over to Stephanie, I just wanted to put this quote out there. It’s a quote by Lonnie Bunch who I’m sure all of is the Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution. And I love this quote because I think it really succinctly sums up what’s at the heart of this question. And so the quote is, museums become better places when they recognize that they cannot be community centers, but that they can be at the center of their communities.

Stephanie Wilchfort:

Hello everybody. Good afternoon. I’m Stephanie Wilchfort I’m the president and CEO O of Brooklyn Children’s Museum in Crown Heights, Brooklyn. And we broadly define our community as central Brooklyn. Central Brooklyn is made up of six, seven neighborhoods, Bedford’s Stuyvesant, Brownsville, Crown Heights, East New York, Flatbush and Prospect Lefferts Gardens. We also include Midwood in there sometimes. But basically the center of Brooklyn. And I’m going to start with a little bit of a story about how we chose to be sort of very specifically geographically defined. So why do we define community? It’s really to think about how we develop and market programming, how we invest our resources. I wish I could say that those were the good reasons why we came to this definition of community. But actually when we talked about defining community, it was born in a moment of crisis.

When I started at the museum in 2015, on my very first day on the job, about 90 minutes into my tenure, I got a call from the New York Times and the reporter said to me, “There is a group of people who are telling us that your museum has forsaken central Brooklyn. You are no longer serving central Brooklyn. You are most interested in serving a group of other neighborhoods in Brooklyn.” Park Slope, Brooklyn Heights, Dumbo, you all may have heard of some of these neighborhoods. They’re the wealthier and whiter parts of Brooklyn. And I was like, “I’ve been here for 90 minutes. Let me just put you on hold for a sec and find out what’s going on.”

If anybody ever wants to talk about a moment of crisis, that quickly into your job, I can do that. But what became very clear right away is that there were a group of people who had self-identified as our community who felt they were not being served, that it was not going to be my choice who our community was. Our community had already self-identified. And I think that’s really important. Sometimes you don’t get to choose who your community is and that can be a gift and it also is hard. What also became clearer was that there was a gap between the people who externally were identifying as our community and the people who we thought we were meant to serve as the community inside. And we talked about the community, they weren’t our visitors. When we talked about our visitors, we were talking about maybe different people or we were talking about a broader group of people.

That is, I think a very common thing. We talk about community engagement. Community engagement is different from public programs and that was very much true at Brooklyn Children’s Museum. We had this sharp distinction between how we engaged our community and the way we engaged community was free service, free afterschool programs. But the way we engaged our visitors was through public programming and exhibits. And that was a problematic construct, at least for us. And I would argue that it’s a problematic construct for everybody. So our first order of business was to get everybody on the same page about who the community was and to remind everybody that the community was not different from our visitors and that we needed to serve everybody in the same way, primarily frankly through exhibits and programs. Most of the people who come to Brooklyn Children’s Museum do not experience our afterschool program.

That is a very small program. Most of the people who experience Brooklyn Children’s Museum experience our exhibits first and our public program second. So how did we do that? One of the ways we did that was by shifting the question. And the question had previously been, who is our audience? And when we answered that question, we were like, “Everybody, everybody in Brooklyn is our audience. Everybody in all five boroughs of New York City is our audience. All families are our audience.” And that was not for us a good way of defining community because there are 2.6 million people in Brooklyn and there are 8 million people in New York City and 8 million people is not a defined community for a community museum like ours. So we shifted the question to who benefits the most from our work? When we asked the question that way, when we asked the question who benefits the most from our work, it became clear that children and caregivers in central Brooklyn, those seven neighborhoods that I mentioned benefit the most from our work.

Why is that? Because Central Brooklyn has about between 850 and 900,000 people and it has roughly three museums. 900,000 people is 300,000 more people than Boston. We have three relatively small, all extremely under-resourced museums in central Brooklyn. So it became clear immediately that our work was going to benefit people in central Brooklyn the most because they were already under-resourced with the physical cultural resources like museums, like big performance spaces. The other thing that was important was some of the people who live in central Brooklyn were particularly underrepresented and under reflected in museums. And so that was an important thing for us to think about. And then also people in central Brooklyn were coming to the museum. So we were geographically close to all of these neighborhoods and we already had the people in central Brooklyn as visitors. So they were already our community.

Again, we didn’t get to choose. And then we had to think about how are we serving our community? And I would just say that we first thought about this by saying, how many things can we say yes to? Big things can we say yes to? So one of the things that we did was we did big surveys of our visitors and of the visitors who live closest to the museum and actually serving families regardless of ability to pay was a big issue for a lot of the visitors who live closest to the museum. So we made that a core tenet of our programming, of our work. Responsive and inclusive program development, that means we co-create our program with partners and with people from the communities that we’re seeking to serve. We’re super serving central Brooklyn schools, so we’re prioritizing central Brooklyn schools.

When we think about our education program, we’re paying our local community, we’re making sure that we’re filtering the wealth that we’re generating through admissions tickets and through philanthropy and through other ways of generating revenue back into the community by partnering with local businesses, with local artists, with local exhibit developers. And also our staff is also our community. So we’re making sure that we’re paying for 100% of their healthcare and a 100% of their family’s health insurance as well. So our employees do not pay any premiums. And that was something that was important to them and it’s important to us. Flexible schedules also really important. What’s important to your staff, they’re also part of your community.

And the last thing is that we provide and share space with other CBOs in our community. When other CBOs or cultural partners need space, we have a lot of space. And we were one of the only physical buildings in our seven neighborhoods that has a big space that we can open to other CBOs. That is a privilege. It is a gift and it is also something that we need to be sharing with other folks in our community and not charging them like prohibitive prices for it, charging a very modest fee to cover our costs, but making sure that that is accessible to as many partners as possible. And I will turn it over to Kristian to talk about Atlanta History Center.

Kristian Weatherspoon:

So yes, my name is Kristian Weatherspoon, I am the vice President of digital storytelling at the Atlanta History Center in Atlanta. And just for a bit of context for our museum, we are a nearly 100 year old history center. It actually began as a historical society and became the Atlanta History Center in 1990. Over those 100 years, we have grown into a 33 acre campus that encompasses permanent exhibitions in our museum buildings, but several gardens, historic gardens and historic homes. And so our official mission is to connect people, history, and culture. So we spend a lot of time and have spent a lot of time historically, our museum is located in the heart of Buckhead. If any of you are familiar with the city, it is one of the more affluent areas of the city.

And so as we speak about what does our community look like, we are fully aware that we are on a mission to broaden that community and to make it more representative of Atlanta itself. So as many institutions after the summer of 2020, specifically in Atlanta, following incidents of George Floyd and a lot of the protests, our institution really took a hard look at how we focused our work in the city of Atlanta. And I think as many institutions were really encouraged to do, we really had to take a look at what the manifestation of that work was. And we decided through a redone basically strategic plan that over the next five years we would focus really specifically on how to capture stories from underserved communities within Atlanta.

And so the outgrowth of that was the creation of a digital storytelling specific department with the goal of telling these undertold stories. And so we really see this as an opportunity for us to not only again connect with communities that historically our institution has not before, kind of being where we are in the city, but also an opportunity for us to be a community resource to these communities. And so what does that look like for us? And to be completely honest, we are still determining what that looks like. And therein lies the importance of, again, that community engagement, really talking with these communities and honestly opening our space for communities to tell us what they want, to tell us how they would like to engage with our institution.

And so we really see the outgrowth of that being really storytelling specific work. And so as we work to capture these lesser known stories and to create a more inclusive institution, over the next five years, in addition to this digital outreach, we are looking at the topic of democracy as another really strategic initiative that we are hoping will allow us to also connect with communities around civic engagement. And I’ll talk a little bit more about that later. And as we look again, forecasting what our next 100 years may look like in the city of Atlanta, we totally recognize that there are gaps in our collecting, how we have collected historically, what communities we’ve collected from. And so this work really specifically is really aimed at again, trying to bridge those gaps through this community work. So I’ll turn it over and talk more about some of our specific initiatives later.

Rima Zalghout:

Hello everyone. I’m just going to bring it down because I’m a little shorter. So my name is Rima Zalghout and I’m from the Arab American National Museum. We’re the first and only museum of its kind in the United States. We are devoted to recording the Arab American experience. We’re also a touchstone that connects communities to Arab American culture specifically. We’re a really interesting museum because we are a national institute and a Smithsonian Institute, but we’re located in the community in Dearborn, Michigan, which is the largest concentrate concentration of Arab Americans outside of the Middle East.

And I am somebody who’s from that community. I grew up around the block from the museum. So we’re like a small but very mighty and devoted team there. And it’s really interesting to work and to do work with this museum because Arab Americans have lived and worked and created in the United States since at least the 1880s. And so people have a very specific idea about Arab Americans. And so when we think about community, we’re thinking about several different groups. We’re thinking about people who have no experience with Arab Americans, we’re thinking about people who think that being Muslim means you are Arab American. We’re also looking at the community in our backyard and then also the pockets of Arab Americans that live around the country. And so the struggle that we have is how do we engage with all of those communities and make them feel seen and make them feel heard while providing content, research, resources, education, programming, all the things that feels accessible to all of these different groups.

Holly Shen:

So thank you. That was wonderful and hopefully that gave everybody a introduction and context to some of the examples and case studies that we’ll be digging into a little deeper. And when we talk about a definition for community, one question that comes up often is how does data and the collection of data or the lack of data, the synthesis analysis of data play into that definition? And so I wanted Rima to invite you to speak a little bit more about that example in the context of your work.

Rima Zalghout:

So this was a really interesting question when it was brought forth to us because nationally, Arab Americans are designated as white. And so we’re actually missing from that conversation nationally. And there’s been a decades long effort to collect data about Arab Americans because we’re designated, it prevents meaningful collection of data about education, employment, housing, healthcare, political representation, anything you can think of, it’s we just don’t have that information. And this reverberates back to the community. So when you ask us how do we collect data about Arab Americans, well that’s a great question because technically speaking, I can’t actually tell you how many Arab Americans walk through the door because it’s not an item on the list that somebody can check off.

There’s another aspect to this as well, which is that the Arab American community is over surveilled. And so there’s a lot of discussion about distrust of collecting this information and it’s definitely a work in progress. But one positive thing we can say is that activists and organizers submitted like 13,000 signatures to the Bureau of Office, the office of Management and budget, to try and change the national census and the hopes that that can reverberate back down to us so that we’re better able to have meaningful data-driven discussions about the community that we’re serving.

Holly Shen:

Rima, would you mind telling the quick story of why Arab Americans aren’t-

Rima Zalghout:

Yeah, so this happened multiple times. I can give you one specific story, but essentially, what happened is that throughout, I would say probably in the 1910s to 1930s, certain Arab Americans at the time sued the US government to be designated as White because they were receiving social services. And so this was a way to circumvent that. And now we’re kind of going back and we’re like, okay, that worked for the 1930s, but it’s 2023 now and we’re ready to be represented meaningfully and also to be named meaningfully. So there’s some discussion about Arab American, MENA, Middle Eastern, North African, SWANA, Southwest Asian, North African, that kind of thing.

Holly Shen:

Thank you. Kristian or Stephanie, do you have anything to add to the question around data?

Stephanie Wilchfort:

Yeah, I’ll just say that at Brooklyn Children’s Museum, we do a demographic survey at the door and we ask every visitor to fill out this demographic survey. And part of the reason we do that is because we want to know that the people we’re intending to serve the community, Central Brooklyn are actually the people who are coming to the museum. So we collect zip code data and that is helpful. And we also do ask people to identify racially. And that has been an ongoing challenge, partly because the categories that the city of New York uses to designate race and ethnicity are the same categories that have historically been used on the census. And those really, if we’re going to actually try and map onto what we know about central Brooklyn or the people we know are identifying central Brooklyn, we need to use those same categories.

But our staff hates to use those categories. People don’t like to identify in those categories. People have a much broader definition of who they are and how they identify ethnically. It is an uneasy compromise that we’re using those categories. And I think Rima talked really well about some of the downsides of those categories, but the worst part of it is they don’t make people feel great, which means that people are not as open to giving us the information that we need. That said, we have been able to collect data from roughly half the visitors that we see give us zip codes. We think that’s pretty representative of the population and maybe a third give us more information than the zip code. And that also is from a statistic standpoint representative, but we’re very well aware that it’s very imperfect. And this is something I think that needs to be an ongoing conversation for all of us at museums, especially frankly as funders ask us for this information. So it’s an ongoing challenge.

Holly Shen:

So I wanted to move to this idea of once you have a community defined or partially defined or defined in some way, how do you create approaches that are responsive to that community? And specifically thinking about interpretation of historical objects or materials or artistic fine arts objects, and then also the reinterpretation of that same material as the kind of definition or the confines of community change or shift over time. So Kristian, do you want to talk a little bit about that in the context of your work at Atlanta History Center?

Kristian Weatherspoon:

Yeah, for sure. As I mentioned, our strategic plan and the reworking of that, we really identified a goal for our institution as being a convener of conversation. In addition to using the resources that we have within our archives and on our physical campus, we’ve really identified that as a way for us to really engage these communities and to really just offer the space to have these conversations about these really contentious histories. Just for a really specific example, our museum deals a lot with historical memory. We have one of our signature exhibitions is the Cyclorama that talks about a 1800s painting that was basically brought to Atlanta and reinterpreted to depict a confederate victory, which it was not.

So a lot of our work and a lot of our time is spent around the reinterpretation of these things that have really shaped our culture. Another portion of that is as a historic home, we own and manage the house that Margaret Mitchell actually wrote Gone with the Wind in. And so during the pandemic, it was obviously a real point of contention, and so we closed it and have taken the last three years as an opportunity to really dig in and reinterpret that space and to help people understand this, it’s not the truth and to really dig into some truth telling work. So for us that reinterpretation looks like specifically not shying away from these just historical truths that have been misrepresented for years.

And so we’ve taken this idea of southern memory on, and we really see that as an opportunity for us to, again, not only put these truths out there, but to then turn around and offer the space to help people contextualize and really provide that context and understand why this was harmful and to help people grapple with that. And so it’s really how we see ourselves as an institution of the future, engaging with communities, providing the resources and the context, but also providing the space and the opportunity to have these really contentious conversations because we think in our communities, especially in Atlanta, a really diverse community, we are still really dealing with a lot of these issues and we see ourselves as being equipped to help provide that solution in conversation in the form of conversation.

Holly Shen:

Great. Rima or Stephanie, do you guys have anything to add around how you create community responsive programs?

Stephanie Wilchfort:

So Brooklyn Children’s Museum has a 30,000 object collection. We were started in 1899. We were the world’s first children’s museum. So it’s been collected since 1899. And for us, much of the thinking about this has been about tabling the collection. We have been obsessed with the collection over the years. We love that collection, but that collection does not have good provenance for a lot of the objects. The objects are from all over the world. We don’t know anything about how they were collected. We just need to hold it for a moment.

And what we’ve really done is focused on creating public programs that are reflecting and representing the current community in central Brooklyn. And that’s been a hard thing to do. I’ll just openly admit that we forwent our AAM accreditation a few years ago because the collection was no longer at the center of the most important thing that BCM could offer our community and the collection is not responsive to our community. I wish it was, but it’s not. And so until we can remediate that and really rethink about it, we’ve tabled a lot of the collections programming. We still have some natural science collection is a little easier to interpret than the cultural collection, but that’s been our approach.

Holly Shen:

That brings up a really great question around collections in general and how they may represent and reflect our communities and what needs to happen to the collections when the composition of those communities change or the remit of the museum in terms of who they serve changes. Rima, do you have something to-

Rima Zalghout:

Yeah, so at the Arab of American National Museum, our collection is donated a 100% by the community that we serve. The museum only opened in 2005, so it’s relatively new. And however, that doesn’t stop us from having similar issues. Maybe not so much in terms of where do these materials come from, but for example, for a long time perhaps the material is more focused on areas of the Levant and collecting so Palestine, Lebanon, that kind of area, and less focused on other countries like Iraq or Yemen or these kinds of things. And that reflection, it becomes reflected in the things that we make available for consumption.

And then we have a very unfortunate, when the museum was made, they made their permanent exhibits, but they made them so permanent that we cannot get them off the walls. And so our exhibits need updating. It’s been almost 20 years and that is a big struggle for us right now. These are materials that were great for 20 years ago, but it’s been 20 years. We need to update it for all the things that have been happening, especially we have a section called Making an Impact. You can imagine how much has changed since 2005 in the making an impact exhibit so-

Holly Shen:

I was wondering too if oral histories play into the idea of collecting stories that may or may not relate to an object or to a moment in history and if that has come up in any of your work.

Rima Zalghout:

I can speak if that’s okay. So just recently we added an oral history department, I guess I would call it. It’s only been a year so it’s very new. We’re very excited about it. In the year, I think they’ve collected over 100 oral histories and they’re just a two person team, so go them, you know what I mean? And they’re incredible. Both of them are from the community as well. So one is [inaudible 00:32:37] and one is Palestinian Christian. And what makes them so great is that they’re able to go out into the communities.

So for example, Patterson New Jersey has a very large Palestinian community, and so they were able to go out and get stories from that community. But in a more centralized way around the city that the museum is housed in Dearborn, Michigan, we’re able to take our oral history and connect it to programming initiatives. So for example, we’re opening a community rooftop garden and we were asking for donations of seeds from our community and with each donation, our oral historians recorded a conversation with the person who donated the seeds. And so now that’s part of our collection and it’s part of the rooftop garden. So there are quotes and the ability to listen to the story of the person who donated the seed is now available to anybody who will visit.

Kristian Weatherspoon:

And I’ll just add that for us, it’s a very kind of similar output when we think about, again, what are the ways that we are engaging with communities and story collection and how do we use these? How do these become parts of our permanent collection? And so for us, it looks a lot like in addition to that strategic plan I mentioned, we developed both a collecting plan alongside that. And so as we identified what those strategic priorities were and the communities in that strategic priority, we set alongside that a collecting initiative that works to again, intently work with those communities. We hired staff along those same lines to really begin that engagement. Some of the outgrowth of that, we have launched recently, many of you may be familiar in northeast part of Georgia in Forsyth County, there was a lynching in 1912 and following the lynching there was an expulsion of all of the Black people from that county.

And you may remember the 1986 episode on Oprah where she went to Georgia. Well, so we have connected with that community and in addition to we’ve identified about 100 descendants from those Black people who were expelled from that county. And as part of our digital storytelling work, we are producing a podcast that really tells that story of displacement. Many of those displaced residents came to Buckhead near our history center. And so a part of that is really connecting these stories from both across the state and across the nation because so many of these issues are national issues. I mean that displacement happened across the country for Black people.

So for us, in addition to again, the outgrowth being the stories that we really hope to tell, but in that part of being community resource, we’ve started an oral history project around that so that those stories are preserved for the future and they are widely accessible. As we talked about that data, our museum before the pandemic did not do a lot of data collection. So a lot of the visitor data that we have we’re starting from scratch. But one thing we did recognize, I think as many institutions, our exhibitions are outdated and we’re in the process of updating those. But we do see digital outreach as that bridge for us. It is the way that we recognize that if we never return to pre-pandemic numbers of visitor engagement, which is for our institution largely not a goal. Our goal is again, to open the doors of our history center, our archives, our research facilities to people whether or not if they come in, it’ll be great but in a digital space. So yeah, we’re working on several fronts to accomplish that.

Holly Shen:

Great, thank you. So obviously, I think being responsive to the communities that museums serves is important, but there’s always a flip side to everything and sometimes it may be necessary to say no. And so the question that I wanted to pose was, how and when do you say no to your community and can no be a responsive practice?

Stephanie Wilchfort:

So I’ll just start by saying the first rule for us in saying no is always to find a couple of yeses that we can say first.

Holly Shen:

The sandwich approach.

Stephanie Wilchfort:

It’s the sandwich approach, but well, it’s more like a half a sandwich that starts with a big stack of yeses and then then no. And I’ll just give a couple of examples of where we’ve had to say no as Holly put it as a responsive practice to broader segments of the communities that we serve. We do cultural festivals almost every month. They are Valentine days that highlight the traditions and cultures of particular communities in Brooklyn. And one last year we hosted, well, every year we host a huge festival for Eid al-Fitr and we have many multiple diverse partners. And one of our partners has a partnership with the FBI where they’re doing public education and they asked if they could bring their partners from the FBI on site for our Eid festival.

And we had to say no and that was also about asking our other partners and finding out from people who we trusted in broader segments in other parts of that community, in the Muslim community in Brooklyn. And the Muslim community in Brooklyn is very big and very diverse. And it started this part of this was recognizing that talking to one person in a large and diverse community is not enough. You have to be talking to a lot of people. But it became clear in some of those conversations that it would cause harm to some members of the community that we were seeking to serve to say yes to this request and that the downside was greater than the upside.

We also sometimes run into religious communities that are very much a part of the fabric of our neighborhoods in Crown Heights that don’t always like some of the performances that we do for various reasons. And that’s another place where we have to think about what are the concurrent programs we’re offering in the museum so that people maybe who don’t feel comfortable with a particular program or performance can go someplace else in the museum and experience something different. And try to be responsive in that way while understanding that we stand behind the programs that we are offering and we don’t want to compromise the integrity of some of those programs and those artists.

Holly Shen:

Great, thank you. So I wanted to circle back really quickly before we open it up for audience questions to something that you touched on, Stephanie in your presentation, which was the question of geography and how geography plays into the definition of and service to communities and how geography can also impact or affect access.

Kristian Weatherspoon:

Yes, I mentioned in our museum is in the heart of Buckhead, we do not have a ton of accessible public transit to the museum. So again, we recognize that that is a barrier for visitors potentially, especially from communities that we are again working really intently to engage. And so it’s a difficult problem to solve. We recognize that it is a problem, but I think for us it again shows up as really putting forth more effort. We have no expectation that in large part the communities will come to us. We recognize that the onus is on us to go to these communities. And so we do that in a number of ways. Like I said, our digital outreach, the growth in that area for us is supremely important for that specific reason because the communities that can get to us are the communities that again, we are trying to broaden, we’re trying to broaden that group.

And so in addition to that, we have two large public programming days every year, King Day and our Juneteenth celebration, we welcome between five to 6,000 people to our campus for that day. The day is free admission. We work with communities to help community organizations get to our campus for that day. And it really is an opportunity again, for us to share the resources and share the work that we’re doing with these communities and to honestly just be a touch point, begin that engagement. And as a result, we do lots of community archiving projects where we work with local community organizations within their specific neighborhoods to again, collect stories, but to also again, share resources, teach communities how to preserve their community spaces, how to preserve the histories in their communities. And if that again becomes something that is represented in the museum, so be it. But if not, again, being that community resource is the most important objective for us in that space.

Rima Zalghout:

So I’m going to answer this question from a slightly different perspective. I grew up around the corner of the museum and like many people in my community, I did not go to the museum until I was well into my 20s, even though I was a teenager when it opened. And the reason for that is I wasn’t necessarily aware of it. And when I became aware of it, the question came up for me of, well, why should I visit the space? I am Arab American, who are they to tell me about myself? And it was a lack of understanding about the breadth of history. I had no idea how long Arab Americans had been in the country.

And so when we think about geography in a very insular way, the question that comes up is how do we show people in this community, many of them who really, at least for the majority of new immigrants who started coming in the 90s, how do we show them that there’s so much more for them to learn about themselves and the impact that they have? And then on a wider scale, obviously being in Dearborn, Michigan can make it really difficult for people to come to visit for variety of reasons. And so during COVID, they brilliantly put on an entirely virtual concert series called JAM3A that was incredibly successful. And so there’s been a lot of discussion about virtual programming to reach people not just in the United States, but also worldwide within the Arab world and outside of it, yeah.

Holly Shen:

Great. Thank you. So we have about 15 minutes left and I wanted to open it up to the audience for questions on this topic.

Speaker1:

Thank you, Holly. Do any of the museums, what is your approach to neuro diversity, just out of curiosity?

Rima Zalghout:

So for us right now, this is a very ongoing conversation. Before the pandemic, we partnered with a program in Detroit called Culture City. We did Sensory Friendly days, but at this point we’re looking to expand that so that it’s more integrated into the everyday life of the museum as opposed to it being something where if you need accommodation, you need to specifically ask for it. So it’s a very live question for us at the moment.

Stephanie Wilchfort:

So anecdotally, we know that a lot of families with children on the autism spectrum and with other sensory differences use our museum because it is such a sensory space. And the thing that we’re doing most now to super serve those communities is to work directly with district 75 schools that have large populations of students who are neuro diverse. That said, this is an area that is also a priority for BCM moving forward, I think we’ve not been as intentional as we could be. I think what has happened is the museum’s talked about disability access and inclusion. And when you think about disability access and inclusion, most people think about people who have mobility challenges. And the reality for us at BCM is that 95% of the people who identify as disabled are identifying as neuro diverse. So clearly, we need to be thinking about that and we need to be talking a little bit more with that community and really talking with also the educators we’re seeking to serve who are bringing groups because that’s the number one way that we’re seeing neurodiverse students.

Speaker 2:

Hi. For both Brooklyn and Atlanta, you talked about serving families regardless of their ability to pay and moving toward a digital engagement model. I was wondering if you could talk about your funding structures for those and how you sustain those types of programs.

Kristian Weatherspoon:

I mean, simply put, our institution has just made a significant financial investment. Again, for us, it’s been the creation of my department really specifically. We are a staff of four and that was kind of, once we identified that as a strategic priority, we made it a priority. And of course, sustainably, we are looking at models for fundraising around this work because it is not revenue generating for us specifically because again, our goal is strictly mission to connect people history and culture. And so we really see this as being the connector for that. But initially again, it was just a budgetary priority that we made. But moving forward, we are really exploring again what the funding model is in fundraising, if that’s helpful.

Stephanie Wilchfort:

So our museum is not free. It is free through a number of very targeted programs. If you cannot pay, we have a access for all initiatives. So we would never turn a visitor away for lack of funds. But we do ask visitors to pay if they don’t qualify for one of the specific programs that we’re offering. And the programs are expansive, like more than a third of our visitors come for free. If you really cannot pay, there is a program for you 100%. But we do ask people to pay. And I think that’s important to say because when if 65% of the visitors are paying, that is one of the ways that we’re funding the 30 to 35% of visitors who truly can’t afford to pay.

The other thing, there are two other ways we’re funding free access. One is the city of New York is providing us funding for free access and the other is through corporate sponsorship. And currently Amazon funds free hours on Thursdays at our museum. And so I would encourage those of you who are thinking about free hours, adding free hours, adding free days to think about corporate partners who would like to be associated with free service and whose name can be headlighted over free service.

Speaker 3:

I have a question about collections. So when we have collections that are no longer serving the community to the fullest extent, what do we do with them? Is there a purpose for them? Is there a way to re contextualize some of these objects or is it a time to move forward into the future and leave the collections behind as history but moving forward with new identities, new ways of thinking? So what’s your opinions on that?

Kristian Weatherspoon:

So for us as part of that collecting plan, deaccessioning is a large part of that. For a lot of those things we recognize that we’ve got to put our stake in the ground and just say, this is where we are going. Yeah, so it’s a part of it, kind of what, and I don’t know that it’s not that we’re saying that these collection items are not important, but again, for us, being the type of institution we’ve been historically, we recognize that it is going to take some radical change to do that. And so that’s the approach that we are taking.

Stephanie Wilchfort:

I just want to say that there’s two big challenge… So I’m not really a collections person, as you might have gathered. And in our case, there are a number of collections that I think we would, deaccession, there are two institutional reasons not to do that. One is time. So where are you going to put your time? Because it takes a lot of time to deaccession things. And it might just be better if you’re really serving, if your focus is serving your community, go find out what your community needs. They don’t probably need you to deaccession those things. Just leave them in the storage room, it’s fine for now.

And the other is what is going to happen to those objects when you put them into the world? These are, in our case, objects that have no provenance. We don’t know where they’ve come from. Ethically, deaccessioning is a real thing and I’m not sure it isn’t better for us just to keep some of those things in the storage room, but I’m not sure about that. And I just want to say candidly, this is not my area of expertise. This is just me as the president of a museum that is a collecting organization giving my opinion on it.

Rima Zalghout:

I’ll make this very quick. I’m going to speak from the perspective of the librarian because I deal with it in that kind of way. The answer for me is utter ruthlessness. If I don’t feel like it belongs, I boot it. For us, it’s a very real space issue. But also I have to think about what are the common things people are coming in and asking for. Is this, for example, we have a junior nonfiction collection for children. It has not been used in probably 10 years. It’s great that it’s there, doesn’t need to belong. Is it taking up space? Probably. And so ruthlessness is my answer I guess.

Speaker 4:

Do you run into any language barriers? And if so, what do you do for your English language learners in your programming or in your museum spaces?

Rima Zalghout:

So the biggest language barrier, of course, is that as Arab Americans, many people speak Arabic. A lot of our staff are Arab American, myself included. And we can speak Arabic to a certain degree. But for example, the Arabic that I speak is very conversational. It is not academic or standard formal Arabic. And so a lot of the difficulty that we have is translating materials so that they’re available to people who don’t speak English. And right now we are actively looking at ways to make our exhibits more properly bilingual. And then in a completely different sense, we have materials in our archive that are all in Arabic and nobody can translate them.

And we had a really interesting example of this where somebody wanted to donate a bunch of books that were in Arabic and we told them we’re not sure what we want this, we translated the title, this is what it is. And it turned out that his grandfather had translated the books when he brought them with him. And when we asked if he was still interested in giving it to us, he was like, “No, no, it’s sentimental now.” And then we lost those books. So there’s a lot, which is fine. To be clear, I’m not complaining about that. But that can be some of two different ways to consider bilingual within our museum space.

Speaker 5:

Thanks. Apologies if this is too nitty gritty, but I just wanted to ask the Brooklyn Children’s Museum, how you ask people to identify that they can’t pay and do you run into any issues in asking people for that information?

Stephanie Wilchfort:

So the way we’ve done it is so if you hold a cool culture card, which is your child is in a headstart program or a low income daycare, you come for free. If you hold an EBT card and are receiving supplemental nutrition benefits, you come for free. We serve our municipal employees, firefighters, police officers, healthcare workers, public school teachers for free. Not necessarily because they can’t pay, but also because that is part of our service to the city of New York. And anybody can check a pass out of any branch library in the entire city of New York and all five boroughs to Brooklyn Children’s Museum at any time. We do not limit those passes.

So there are a number of different ways that we try to open up the free admission. We don’t actually say at the front desk, “Can you pay?” Or, “Can you not pay?” But if somebody comes to the front desk, and this happens from time to time and says, “I’m a parent, I forgot my wallet.” Which happens frequently, we’re not like, “Well, go home and get it. Drag your toddler back.” And so that does sometimes happen that people come to the front desk and they say, “I just can’t pay you right now.” And we’re like, “That’s fine. Just give us your zip code, fill out our survey, it’ll pay itself forward.”

Holly Shen:

Great. So thank you everyone for joining. This is our contact information if you want to get in touch with any of us. And thank you again to our wonderful panelists.

Comments