This article originally appeared in Museum magazine’s November/December 2023 issue, a benefit of AAM membership.

At the McClung Museum, a NAGPRA assessment strengthens collaboration with Native Nations on a current and future exhibition.

Since the passage of the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA) in 1990, museums have struggled to come to terms with the law, which requires that any institution receiving federal funding provide Federally Recognized Tribes with an inventory of all Native American Ancestral Remains and associated funerary objects (Belongings), along with summaries of sacred and patrimonial items connected to Tribal identity, for possible Repatriation.

In the 30 years since NAGPRA’s passage, museums have been slow to Repatriate Ancestors and Belongings to Native Nations, to redress imbalances of power in the museum sphere, and to collaborate constructively with Indigenous groups regarding the interpretation and care of their material culture. Over the past few years, pressure from Native Nations, museum employees, and media coverage of Repatriation have begun to move the needle.

The McClung Museum at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville (UT) has also struggled to implement both NAGPRA and voluntary Repatriation effectively. The McClung Museum was partially founded to serve as a repository for millions of archaeological items excavated in the 1930s by UT in partnership with the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA). Until recently, a Euro-American archaeological narrative has dominated our space, and, too often, the museum made decisions about what parts of collections fell under NAGPRA rather than ceding this authority to Indigenous communities.

Over the past four years, the McClung Museum has taken steps to make all Belongings available for return, educate our visitors on NAGPRA, and rework our exhibition on Native Nations with ties to Tennessee. All of this work is being done in partnership with Native Nation collaborators.

Assessing the Collection

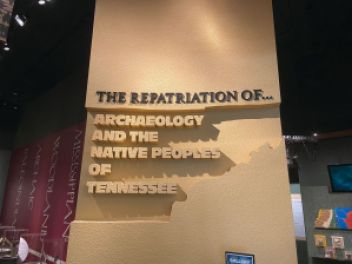

In 2019, the museum conducted a NAGPRA assessment of all remaining archaeological objects on display, creating an inventory for each display case along with corresponding photographs. This posed a challenge because the museum’s primary exhibition showcasing material culture from an archaeological context, “Archaeology and the Native Peoples of Tennessee,” was installed around 2001, and some items only had limited documentation.

In August 2021, UT Director of Repatriation Dr. Ellen Lofaro invited 21 Tribes associated with the state of Tennessee to a meeting to discuss the museum’s NAGPRA assessment of its exhibitions. Eight Tribes agreed to participate, two deferred, and the remaining did not reply. The official virtual consultation meeting was held in December 2021 with representatives of each participating Native Nation.

While a portion of Belongings were removed from display in 2018 as part of a formal Repatriation process, the representatives in attendance expressed their concern that all Belongings had not been removed at that time. Many Native Nations’ representatives also expressed frustration at being left out of earlier exhibitions or display consultations and meetings.

Immediately after this 2021 consultation, the museum’s leadership team, curatorial staff, and collections staff made plans to voluntarily remove the remaining 142 known Belongings as well as 164 items with limited provenance. We also chose to cover up interpretation that was offensive to our Native Nation collaborators: for example, a photograph of an archaeological excavation of a burial mound; a line drawing of Ancestral Remains; and a dog burial made with a facsimile, which nevertheless suggested an original burial.

From January to March of 2022, over 300 items were carefully removed from view. That spring, the museum also recalled all its archaeology loans for NAGPRA reassessment. Some loans had been out for more than 30 years and included Belongings.

NAGPRA Education

It was immediately clear that we had two choices for the former “Archaeology and Native Peoples of Tennessee” gallery, now without around 25 percent of the items formerly on display. The museum could close the gallery and, from the visitor’s perspective, ignore the massive changes happening within our walls. Or we could highlight these changes in a display on NAGPRA until we were able to install a new and appropriate exhibition on Native culture in consultation with those communities. The impulse toward transparency was immediate and strong.

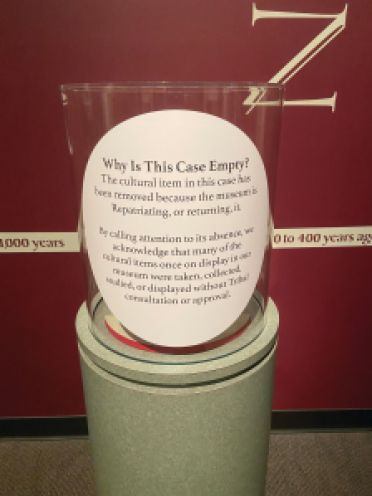

Taking cues from Steven Lubar’s 2018 Medium post “Exhibiting Absence,” we wanted to use the new emptiness of much of the exhibition as way to explain NAGPRA in an impactful way. We realized that it was in fact the emptiness that lent itself to a visual and literal representation of Repatriation. The absence in our gallery highlights previous and outmoded conventions that we used in our space, such as an emphasis on chronological time based on archaeological timescales, lack of representations of contemporary Native Peoples, and an omniscient scholarly curatorial voice.

We knew that many of our visitors wouldn’t be familiar with the law, so the first step was to define NAGPRA. However, we wanted to go further by also talking about sovereignty, NAGPRA as a human rights issue, our role as stewards, our commitment to collaboration and not just compliance, moving beyond NAGPRA, and, perhaps most importantly, visibly centering Native voices by highlighting the significance of NAGPRA to them. Once we had this framework, the text for the exhibit-within-an-exhibit came together relatively quickly.

We called the new exhibit an “intervention,” because while we deinstalled and removed over 300 items, the only added elements were new interpretation explaining why items had been removed and why it had been inappropriate for them to be on view in the first place. New panels, overlays, and didactics were added to the space in a simple yet powerful black-and-white color scheme that distinguished them from the earth tones of the former exhibition.

These called attention to the empty case work, asked open-ended questions for visitors to reflect on, and attempted to preemptively answer questions that visitors may have during their time in the exhibition. Most impactfully, we added massive panels on accent walls with quotes from Native Nation partners to prominently center their voices in the space.

While we knew non-Native visitors would have questions about “ownership” and what happens to Repatriated items, we attempted to address some of these questions while leaving out sensitive information not appropriate for public consumption. Our Native Nation collaborators pointed out language we had used that was harmful or incorrect. For example, they emphasized the capitalization of terms such as “Repatriation,” “Tribe,” “Nation,” and “Ancestor” to reiterate their importance and not referring to Belongings as “objects” or “artifacts” to formalize that they are inappropriate components of museum collections.

We have posted photos of this interim exhibition and its text on our website so that it may guide or inspire others as they deal with these challenging issues. Since opening the exhibition, we have given tours and had important conversations with representatives from the Tennessee Division of Archaeology and the state archaeology offices as well as Tennessee State Parks and the TVA (which also generously contributed monetary support for the exhibition).

Moving Forward

Thousands of Ancestral Remains and material culture items are held or legally controlled by the museum, which serves as a repository for hundreds of archaeological sites investigated by TVA, the US Army Corps of Engineers (USACE), and others. Currently, the museum is working on Repatriation claims for these Ancestors, Belongings, and additional items subject to NAGPRA in partnership with UT’s Office of Repatriation, the TVA, and USACE.

Nevertheless, the museum’s goal is to move beyond NAGPRA to address the broader ethical treatment of Indigenous objects, designs, images, and sensitive topics on display or housed at the museum. This exhibition has given us the opportunity to reexamine our commitment to our Native Nation community partners and move forward in a way that goes above and beyond what NAGPRA legally requires.

The final phase of changes to the McClung Museum’s “Archaeology and Native Peoples of Tennessee” gallery will be to deinstall the space starting in 2024 to prepare for a new exhibition tentatively titled “A Sense of Indigenous Place.” The exhibition, which will feature contemporary works by Native artists, is co-curated by representatives from four Native Nations and centers their interpretation of Indigenous relationships to mounds and their continuity as sacred spaces. Placing the exhibition in the McClung Museum’s largest, centerpiece gallery makes a clear statement about our commitment to including Indigenous voices in our exhibitions.

NAGPRA has asked museums, anthropologists, and archaeologists to fundamentally reconsider our purposes and practices. We subscribe to what Ben Garcia wrote in a 2019 Museum article on decolonization: our museum “no longer view[s] the process of obtaining consent for holding Indigenous belongings as a task to check off our ‘to-do’ list. Rather, it is our work moving forward” [emphasis ours].

We now understand that our work as museum professionals is to connect to the communities that we purport to represent—and we are empowered by that realization. Embracing this work presents new opportunities for museums and museum practitioners, as we consider how to develop meaningful relationships and infuse our work with compassion and humanity.

Tips for Working with Native Nations

Following are some of the lessons we’ve learned in working with Tribal Historic Preservation Offices (THPOs) and collaborating with Native Nations.

Working with THPOs

THPOs typically deal with Repatriation and NAGPRA on behalf of Native Nations. Museums’ first point of contact when dealing with NAGPRA and Repatriation should be through this official channel. THPOs may also choose to include museum/interpretation/cultural experts from their Nation in collaboration with your museum, but it is important for museums to understand and respect the official political structure of Nations and their offices.

Compensating editors, writers, and cultural experts for their time and expertise is crucial. However, some THPOs may not be allowed to take monetary payment since this type of work is sometimes considered “part of their job.” In these cases, museums should determine another form of compensation for collaborators’ work.

THPOs and other Native Nation officials are often underpaid, under-resourced, and very busy. While working with independent Native artists, curators, or other experts under contract may enable shorter timelines, a 90-day review period is typical for THPOs. Plan accordingly.

Collaborating with Native Nations

Consider an editorial or language guide for your exhibition and when communicating to and about Native Nations. Language is powerful—remember that capitalization (e.g., of Native, Indigenous, Repatriation, and Ancestors) is a form of respect and acknowledgment. Some language regarding “ownership” and settler concepts of commodification and law will be problematic and will require careful editing.

Official NAGPRA legal consultation is different from collaborative work on an exhibition. Clarify in writing the expectations for collaborators, including schedules and due dates, compensation, and what framework will be used for a project. Invite collaborators to give feedback from the beginning of the project, including on the project’s framework.

Ask collaborators what goal they or their community has for a specific project and work together to set the rules for engagement. We suggest using the Core Tenets of Indigenous Methodologies developed by curator and scholar heather ahtone (Chickasaw Nation) as a starting point:

Respect (for knowledge, for people);

Reciprocity (bringing the best of ourselves to work toward a common goal);

Relationships (mutually beneficial, shared authority); and

Responsibility (related to goals set by team, budget, and schedules).

Finally, keep in mind that perfect is the enemy of good. Too often museums don’t begin this type of work because they are afraid of failing or not getting everything perfect. This fear is one of the main obstacles to decolonizing museums.

Resources

Repatriation of Archaeology & the Native Peoples of Tennessee

mcclungmuseum.utk.edu/exhibitions/nagpra-intervention-archaeology-the-native-peoples-of-tennessee/

UTK Office of Repatriation

provost.utk.edu/academic-affairs/nagpra/

heather ahtone, “Opening Keynote: Decolonizing the Museum: what does it mean to serve the community?” Museum Computer Network, October 5, 2021

mcn.edu/resources/opening-keynote-heather-ahtone-decolonizing-the-museum-what-does-it-mean-to-serve-the-community/

Ben Garcia, Kelly Hyberger, Brandie Macdonald, and Jaclyn Roessel, “Ceding Authority and Seeding Trust,” Museum, July/August 2023

aam-us.org/2019/07/01/ceding-authority-and-seeding-trust/

Christina Kreps, “Reclaiming the spirit of culture: Native Americans and cultural restitution” in Liberating Culture: Cross-Cultural Perspectives on Museums, Curation and Heritage Preservation, 2003

https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203389980.

Steven Lubar, “Exhibiting Absence,” Medium,

December 2, 2018

lubar.medium.com/exhibiting-absence-36c5552613ba.

Comments