This article originally appeared in Museum magazine’s January/February 2024 issue, a benefit of AAM membership.

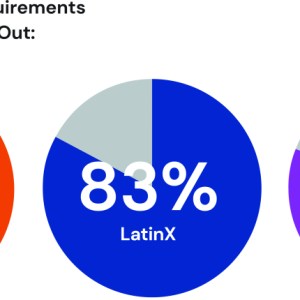

Sixty percent of Americans may find their job search stalling when they hit a “paper ceiling” that ensures that applicants without a four-year college degree advance only so far. This requirement excludes 70 percent of Black job seekers, 80 percent of Latinos, and three-quarters of American Indians and Alaskan Natives.

Many of the positions above this ceiling don’t actually require college experience, and many potential workers have acquired relevant skills through alternative routes, including community college, military service, and on-the-job experience. But requiring a degree has become a common practice in part because it is an efficient way to filter a deluge of digital applications.

The paper ceiling doesn’t just keep people from getting jobs; it damages lives in a host of ways. In the US, people without a four-year degree are less likely to own their own home, are more likely to suffer from depression, and have a life-expectancy eight years shorter than their college-educated peers. While it’s difficult to untangle cause and effect, it’s clear that barriers to hiring help fuel the social and economic stratification of society.

Museums and the Paper Ceiling

Data suggests museums have succumbed to “over-credentialing” as well. Ninety percent of museum workers represented in the last national salary survey, in 2017, held at least a bachelor’s degree, versus 33 percent of the general population. More than 77 percent of technician/preparators (a position described as “typically requiring manual skills related to duties”) have a four-year degree or higher. This overshoot may stem in part from the attitudes and behavior of job seekers: for example, highly educated creatives may see museum employment as a desirable way to fund their independent work. However, having a large pool of highly credentialed applicants can normalize museums’ expectation that they can, and therefore should, fill these positions with college graduates.

Two challenges are pushing museums to revisit traditional hiring practices, the most recent being the nonprofit labor shortage. As museums recover and restaff following the pandemic, 60 percent of directors report they are having trouble filling open positions. Another impetus is that many museums are stalling or even losing ground in their efforts to attract and retain a more racially diverse workforce. Facing these challenges, museums might want to rip down the paper ceiling to widen the pool of potential applicants, increase the diversity of their workforce, and contribute to an equitable society.

Other job sectors are already “dropping the degree.” In the past year, major companies including Kellogg’s, General Motors, and Bank of America announced they will stop requiring four-year degrees for a wide variety of positions. Governments are trying it, too: in 2023 Virginia became the 30th state to review roles and remove unnecessary degree requirements from thousands of public-sector jobs. As a tool to advance diversity, equity, accessibility, and inclusion (DEAI), degree reform is systemic and potentially sustainable, in contrast to one-and-done approaches that rely on diversity training seminars or job fairs.

In museums, the degree in question might be a B.A. or B.S., but for some positions it might be a master’s or a Ph.D. Expectations regarding advanced degrees are even more exclusionary than undergraduate degrees, with respect to race and socioeconomic background, and often result in people embarking on museum careers burdened by significant student debt. It’s worth remembering that museums’ focus on advanced academic credentials is a relatively recent development. The ranks of successful, prominent directors without advanced credentials include Julianna Force, who began as a personal secretary and rose to become founding director of the Whitney Museum of Art in New York City in 1930; J. Carter Brown, who held an M.B.A. when he became director of the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC; and Ron Chew, who did not have a bachelor’s degree when he became executive director of Seattle’s Wing Luke Asian Museum in 1991.

If Not Degrees, Then What?

Degrees are often used as proxies for criteria that wouldn’t withstand scrutiny. It’s well documented that, left to their own devices, people tend to hire applicants they feel comfortable with, people who share their background, interests, experience, and cultural references. That very human tendency is directly at odds with museums’ desire to recruit and retain staff who reflect the racial and cultural diversity of their communities. Weaning an organization from over-reliance on credentialing starts with managers taking a hard look at the skills a job really needs. If a position requires time management and social and communications skills, for example, what other ways might applicants demonstrate these abilities?

Some employers are replacing degree-based hiring with “skills-based hiring,” assessing applicants’ practical knowledge, experience, and demonstrated skills and competencies. These approaches come with their own drawbacks. Some employers have implemented “challenge-based hiring”—requiring applicants to brainstorm ideas, solve a problem, or write an essay. This imposes a time burden on applicants, and in some cases asks them to donate material of real value (whether or not they get the job). Degrees are binary—an applicant does or doesn’t have one. (Granted, degrees from some institutions may be more prestigious than others, but that’s a whole other bundle of bias.) Knowledge and experience are more nuanced and harder to assess. How can museums create systems for reviewing applications that are fair and equitable but also don’t eat unreasonable amounts of staff time?

Once a museum has recruited a more diverse workforce, managers face another set of challenges: ensuring these new staff members want to stay. Employers may need to provide training in hard or soft skills and examine the organizational culture to ensure it is welcoming for new hires who don’t share the background, norms, and experiences represented in the dominant institutional culture.

It may not be a simple solution, or a magic fix, but examining when they might want to drop the degree for particular roles could be a healthy first step for museums to take on the road to effective, fair, and equitable hiring.

Personal experience suggests that shrinkage in practical responsibilities often accompanies inflated hiring requirements. As the resumes of employees become more exhaled, the availability of these folks to take on fundamental, day-to-day responsibilities is reduced. As an entry level employee at a world-famous museum I once had a deputy director (from an academic background) ask me “Now you’ve worked, haven’t you?”.