Whether constructing a new building, growing your endowment, or simply raising money for a program, campaigns are complex endeavors. Even the most organized campaigns can put staff, trustees, and volunteers to the test. Watch the San Diego Museum of Art and CCS Fundraising as they share the museum’s journey to launch its first capital campaign in over 40 years.

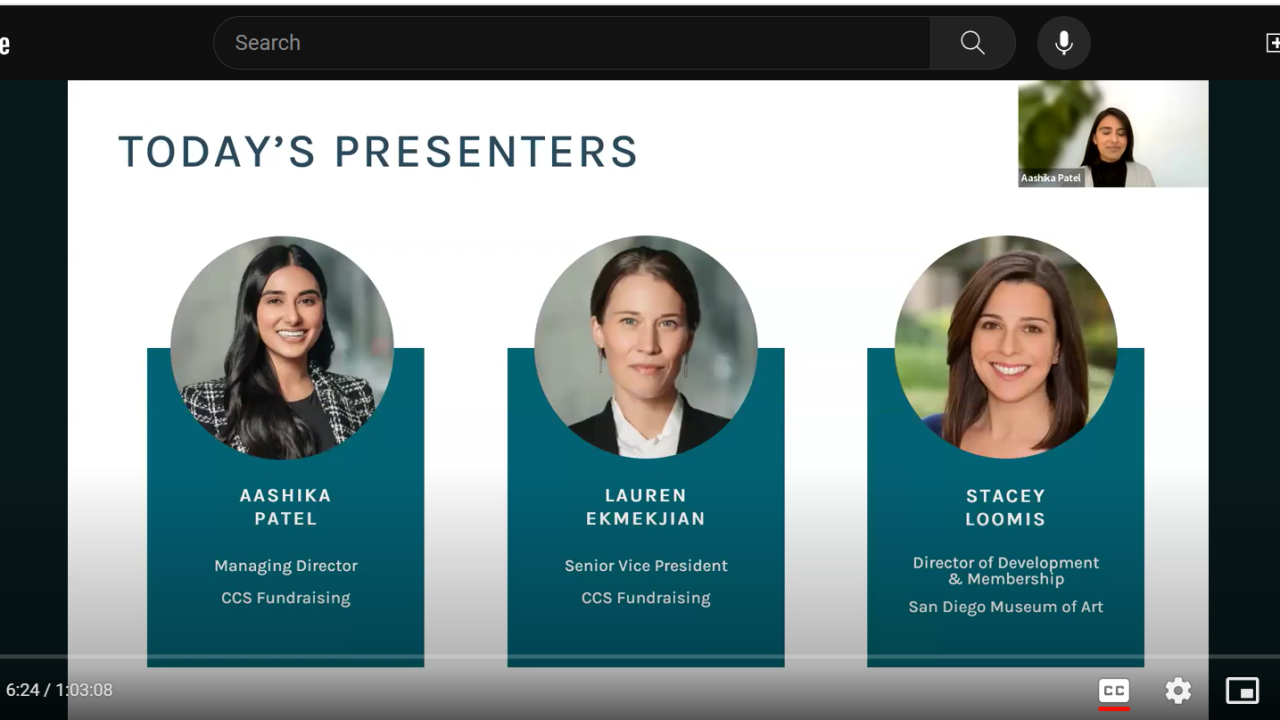

Presenters:

- Aashika Patel, Senior Vice President, CCS Fundraising

- Lauren Costello-Ekmekjian, Vice President, CCS Fundraising

- Stacey Loomis, Director of Development and Membership, San Diego Museum of Art

Click here to access the slides.

Transcript

Tiffany Gilbert:

Hello. Welcome and thank you for attending AAM’s first Financial Wellness Webinar series. Today is our third webinar within this series, How Do You Know You’re Ready for a Capital Campaign? Where Do You Start?

This session was very popular during the in-person AAM annual meeting, and believe it is fitting to be a part of this series. Before we begin, on behalf of AAM staff, we would like to thank this amazing team of panelists for agreeing to share their expertise in this format and appreciate the time they’ve taken out of their busy schedules to be a part of this series.

My name is Tiffany Gilbert. I am the director of meetings and learning programs here at AAM. And I have a few items I’d like to share with you before we begin the session. There are several AAM staff monitors here to support the panelists, and we’ll be collecting your questions and comments. That will be shared with the panelists as often as requested.

For the sake of time, we may not be able to highlight all comments or questions, but they will all be collected and shared with the panelists in a post-webinar follow-up email. The recording, slides, and any other resources will be added to the webpage following captioning, which generally takes about a week. We will send an email to all registrants once they’ve been uploaded. That link will be added to the chat during this session. This webinar, along with the other webinars within the series, will be recorded and available publicly through April 27th. Following that date, they will be available in the AAM resource library, in which all AAM members will be able to access. The resource library has dozens of articles, resources, and tools specific to various topics, including financial wellness, development, and membership.

A link has been added to the chat. Also, for those of you interested in connecting with other museum professionals to discuss the topics focused on development, fundraising, and philanthropy, we invite you to join their community and Museum Junction. A link will also be provided in the chat. Again, we’ll follow up with an email providing you with links and resources outlined in today’s webinar, along with details and registration information for any future webinars within the series. I will now turn things over to our amazing presenters, Aashika Patel, senior vice president of CCS Fundraising. Thank you.

Aashika Patel:

Thank you so much. Hi everyone. It’s great to be with you today for this webinar, and we really appreciate you taking the time to join. We are excited to bring this presentation to a wider audience following last year’s conference, and today we’ll consider campaign readiness and getting started with campaign planning. I just want to take a moment to thank the AAM team for offering us this opportunity and really for facilitating this process. So, let’s go ahead and dive in.

My name is Aashika Patel, and I am a managing director at CCS Fundraising. I’m joined by my colleague, Lauren Ekmekjian, who is senior vice president with CCS, and our client partner, Stacey Loomis, who serves as director of development and membership at the San Diego Museum of Art. Together we work closely to manage the short-term and long-term next steps and goals of the campaign to fund the future of the museum.

For a little bit of context to today’s topics, I’d like to share a bit about CCS before I hand it over to Stacey to introduce SDMA. CCS is a fundraising solutions firm. We partner with nonprofits to design and implement projects that ultimately lead to major gift outcomes. Lauren and I are based out of our Southern California office, and our colleagues are spread out across the US and Europe. We partner with about 700 nonprofits annually to help plan and lead significant fundraising initiatives. We are really proud to have partnered with SDMA for the past two years on their campaign, and I’m going to ask Stacey to share just a bit more about the museum.

Stacey Loomis:

Thank you, Aashika. It’s really an honor to be here today. Thank you all for having us. As Aashika mentioned, my name is Stacey Loomis. I’m the director of development and membership for the San Diego Museum of Art. The San Diego Museum of Art is San Diego’s oldest and largest visual arts institution.

We’re also the region’s only encyclopedic arts institution in our county. We are approaching our hundred-year anniversary in 2026. Last year, we welcomed almost a half a million visitors, a bit over 450,000, which now has exceeded our pre-pandemic visitor numbers. In 2023, we merged with the Museum of Photographic Arts, which is also located here in historic Balboa Park in San Diego. And now we have over 32,000 objects in our permanent collection. The merger with MOPA brought on an additional 10,000 works of photography that we now have in our permanent collection. We have over 450 volunteers who work with us annually, as well as a robust group of docents who go through a two-year training program and provide a lot of the day-to-day interactions with our visitors. And I think from here, I will hand it back to Aashika.

Aashika Patel:

Thank you, Stacey. Here’s just a brief overview of what to expect in today’s webinar. We’ll walk through what at a high level are the elements required for a successful campaign. And then we’ll spend some time digging into the pre-campaign activities that will help your organization build a strong system of support as you embark on a campaign and campaign planning. We’ll look to SDMA to share some real-time examples from their campaign effort to date. And we’ll aim to end with just a few minutes remaining for questions and answers, so I’ll ask folks to please place questions in the chat as we go through the presentation, and we’ll do our best to field them at the end. Firstly, we’d like to hear from the audience through a quick poll.

Thank you to everyone who put your name and your organization in the chat. Is your museum currently conducting a campaign effort? Just take a couple of seconds here for everyone to participate. Oh, you’ll see the poll pop up just there. If you could go ahead and answer in the poll, that would be perfect. All right. Thank you. So, we’ve got a good half of the folks here are not in a campaign but considering a campaign. So, this is the perfect place to be at the right time as well. For those organizations that are in campaign, congratulations in pushing forward in that work, and we really hope you are realizing some of those campaign goals that you’re pursuing. And for those not in campaign and not considering, this will be a great informational session. I’m going to spend the next few slides getting us oriented with key elements needed for a successful campaign. And one of the first considerations in campaign planning is what type of major fundraising effort are you pursuing? Are you looking at a comprehensive campaign or a standalone campaign? Comprehensive campaigns are typically broader in scope and size than a standalone campaign.

We rely heavily in a comprehensive campaign on a case for support that really expands and maintains an organization’s mission overall. We count all gifts and pledges over the course of the campaign period coming into an institution in a comprehensive campaign, including donors’ annual support and annual support at large. Comprehensive campaigns are generally longer. They take somewhere between three or five years, or even more. And then standalone campaigns are focused and targeted. Think capital campaign or endowment campaign.

A standalone campaign counts extraordinary one-time investments from donors for a specific purpose above and beyond their annual giving. So, unlike comprehensive campaigns, standalone campaigns are typically shorter in timeline, around 18 months to two and a half or three years. The SDMA experience represents a standalone campaign, which Stacey will cover the details of in just a few minutes. A strong, well-phased campaign typically follows an arc like the one illustrated here. And these phases can overlap, they can be shortened, they can be extended. But each phase represents an important milestone in the campaign. And we generally find that most campaign aspirations are born out of some type of formal or informal strategic planning process. And in that process, it is revealed what exactly increased dollars are going to be needed for. Is it for buildings? Is it for sustainability? Is it for programs? Expanding your reach? And from that strategic planning process, these needs are identified.

From there, organizations tend to start exploring a planning study or a feasibility study. And during this phase, you’re looking to really draft some of the materials and the early messaging of what your institution is planning. You want to put together these early ideas to start building some stakeholdership and start building some consensus around the direction of your future vision. During the planning and feasibility study is also when you’re going to want to screen and segment your donor base, just to get a sense of what does the prospect landscape look like as we get ready to think about some type of major gift fundraising effort? And as I mentioned earlier, during this phase, instilling buy-in, instilling ownership among your volunteer leadership and among your most loyal donors, is really going to be key. That will set your institution up for entering into a campaign planning and activation phase that feels like it already has some momentum and is on its way to some progress. You focus a significant amount of time from there on your leadership gifts and your major gifts, wanting to secure a good 60 to 80% of your fundraising before launching into a public phase. And this is sort of strategic, having this early phase or silent phase and then a more public phase, allowing your organization to really make significant progress to goal, and then launching something more publicly that you know is going to be successful. Another consideration before launching into a campaign is thinking about a balanced fundraising model. And when we explore potential campaigns, one of the first things we consider is where is the fundraising model overall? Where exactly is the density of donors in terms of individual contributions? But also where are the biggest gifts coming from? And what we like to see is organizations that have about 10 to 30% of their funding coming from a number of smaller gifts at the annual fund level.

These are renewable sources of gift income. And then we’d like to see 70 to 90% of funds coming from the top of your pyramid. Those major gifts, those planned gifts, deferred gifts, all of that kind of counts in that top part of the pyramid here. Donors need not remain in that respective category. Ideally over time, what you’re trying to do is move donors up the pyramid from the annual fund level to the major gift and planned giving levels through deeper engagement, deeper stewardship. And the campaign provides an opportunity to take a look at your donor landscape and what exactly engagement and moves management is going to look like over the next several years.

In addition to considering the balance of your current fundraising model, segment your existing donor base and think strategically about where your last donors are, where your current donors are, and where your new donors fall on that pyramid. So, there are different ways of thinking about the donor landscape, both currently and in the future. There’s going to be an element of acquiring new donors or looking back to previous lapse donors to reengage them, upgrading gifts from your existing donors, deepening that engagement, looking for a greater investment. And then finally, sort of stewardship or the renewal of gifts from existing donors. And these efforts not only help you and your team to get a better sense of where the opportunity lies in your current fundraising model, but it also sets you up for success when it comes time to engage in pre-campaign planning activities. I’m going to turn it over to Lauren at this point to walk us through kind of the critical steps needed as you’re taking your first steps in launching your campaign.

Lauren Ekmekjian:

Thanks, Aashika. It’s nice to be with everyone today. In thinking back to the arc of a successful campaign that Aashika shared on the previous slide, we often see that planning and feasibility study, and even the early campaign planning phases and activation, they typically take place in sequence, though it’s not uncommon to see these activities start to overlap, especially at the tail end of the feasibility study phase.

So as Aashika shared, this is an important time to test our messaging, to screen and segment our donor base, and to build strong buy-in amongst our donors and our volunteer leaders. So, to put some structure around that, there are four main pillars that we typically think about that help us to build a framework around these first critical months of planning. And when in doubt, we always check back to how we can be advancing our work in each of these four elements. Your case for support typically is your central document or set of documents that’s donor facing, and crafts the vision for your campaign or your fundraising effort. And this document should really evolve over time, and it should remain attuned to feedback and refinement, both from your community, your donors, and stakeholders who playing a role in your project or campaign.

Your leaders involve a deep commitment from your board of directors, if you have one. And it may or may not involve a small but close group of volunteer leaders who can help guide your effort and serve as ambassadors to your campaign. We typically think of these as campaign cabinets or campaign planning committees. We’ll talk a little bit more about that when we share the SDMA experience. And of the four elements here, we’d like to say that your prospect list most likely is going to evolve on a weekly or sometimes daily basis. This is a working list of the individuals, foundations, and corporations that have the potential to support your campaign at some level, and we think of this as kind of a working list, always in evolution over time.

Your plan is the timeline to complete your campaign, and the policies and procedures and guidelines that outline the manner in which you’re going to complete it. Your plan should remain nimble, of course, to changing conditions, but setting a clear roadmap early of benchmarks and intermediary goals along the way for your larger goal helps keep everyone accountable and motivated. I’m going to dig a little bit more into each of these four pillars for a couple slides, and then we’ll talk about the SDMA experience. Elements of a compelling case. So, a case for support may look like a written document or a brochure or a video.

Regardless of the format that makes the most sense for your organization, there are some key questions that a case for support should answer. Who are you as an organization? What is your organization do in your community? How much do you need support right now as opposed to later? And what does the amount look like in terms of philanthropic support that’s needed? And I’d say that a good case for support answers these questions, but a really great one takes it one step further and demonstrates the impact of philanthropic support for your organization.

I shared earlier that volunteer leaders could include board members or dedicated members of your community. Either way, they share some common characteristics. They are typically respected leaders in your community. They are strong communicators. That doesn’t need to be someone who’s right up front always presenting, but someone who can really speak to the constituents in your community effectively and they’re trusted. They hopefully support your organization financially and have a philanthropic investment in the campaign. And maybe most importantly, they’re a partner to you and a connector to your community, and hopefully have to be a confidant and a support to you. It’s an added benefit when a volunteer leader has an inspiring story or a meaningful connection to your mission. And strong leadership really goes an exceptionally long way in strengthening your campaign, which we’ll chat about shortly with Stacey. Identifying potential prospective supporters for your campaign is a little bit of an art and a science.

When considering a potential supporter and whether or not they’re a strong candidate to support your campaign or your fundraising effort, we look for the intersection of three main qualities. Do they have the affinity to support your organization? Do they have the financial ability to consider a significant commitment or a major gift? And do they have the access currently to your organization or an existing relationship with members of your team so that they know the work that’s already happening at your organization or for the campaign? And I’ll say that prospects don’t need to have all three of these qualities immediately to be a strong candidate.

Oftentimes, it can be as simple as asking ourselves, how can I ensure that all three characteristics are being met through our cultivation and stewardship efforts? So, this is a process over time. And if the previous slide articulates the art of prospecting, then this slide highlights a bit of the science. There are a few specific tools that we want to share that can be really exceptionally helpful in identifying major gift prospects, which I’ll just touch on briefly here. Wealth screening and predictive modeling takes a look at your current donors, and by estimating their philanthropic capacity based on public information and forecasting their future giving behavior, we can start to sort what may look like a list of 10,000 possibilities, just as an example, down to a much more intentional list of 250 or so informed prospect suggestions.

An RFM analysis is a pretty quick and simple tool to look at your current donors based on their giving behavior, specifically how recently, how frequently, and at what volume your current donors are giving. And by assigning different weights to this behavior, typically your most engaged and generous donors will rise to the top, and that helps you identify some of your more priority prospects. And if you’ve spent some time digging into your donor base and you have a strong list of prospective supporters, it also helps to put a system in place to gauge readiness for a request for each of those individual prospects. This is an example of a timeline and activity tracker to help you and your team create a plan for each individual prospect, and to start to outline the specific steps that are needed to reach your ultimate goal of asking for and closing a campaign gift. We always like to say that each individual donor is its own campaign in its own right. There is a path to bring a donor in and bring them to a gift, and something like a sample timeline and activity tracker can help get your team all on the same page about how to get there. I’m going to close this section out by summarizing some key benchmarks that are needed to start strong with your campaign planning effort. And it helps to ask you and your team and your organization if you can check the following boxes.

Have you identified your goal and the timing for your campaign? Is your case for support clearly articulated, and is it currently resonating with your supporters? Do you have strong leadership in place, both at the board level and among your volunteers? And how deep is your bench of prospective supporters? And if you were asked tomorrow who are your top five to 10 prospects, do you know who those prospects are? And last, what is needed to appropriately staff your campaign? Is the infrastructure in place to dedicate the time needed to execute on a campaign or fundraising effort? From here, I’m going to hand it over to Stacey to walk us through how we are answering these questions in real time at SDMA.

Stacey Loomis:

Thanks, Lauren. So, to begin with, we’re going to take a quick step back. Because while we are a couple of years into the work we’ve been doing on the campaign and with CCS, we have been talking about the needs for a campaign and expansion for far more than 10 years actually. Our executive director and CEO, Roxana Velasquez, joined the museum about 13 years ago. And when she came on, she brought a very different perspective on the institution overall, and as a result, we’ve seen a lot of growth. Our visitor numbers have doubled under her leadership. Our programs and exhibitions have increased. And so, it became evident very quickly that our facility was no longer able to serve us. And our facility is nearly 100 years old.

These conversations had been going on over time, over decades. But Roxana has really advanced that. And so, there’s been about 10 years of discussions about what we need to do to improve this facility and how we can grow to support the next generation of visitors and arts patrons. So, with all of the growth we’ve had, it’s only really exacerbated the need to move forward with this project. And as Aashika shared, in terms of campaign timelines, we also have had a number of specific phases in our planning process here. I will note that we did a strategic planning process well before the campaign planning, and it did inform what became a four-month pre-campaign planning effort in the summer of 2021. During this time, there was a number of discussions and interviews with our constituents, with trustees, supporters, volunteers, individuals throughout our community who were really invested in this museum. And we did a full in-depth analysis of our donor database to better understand the capacity that we have to support this project.

After completing the campaign study, we then entered into a twelve-month campaign planning process to really put all the pieces into place, to formalize our case for support, and to really begin going out and asking early supporters to be a part of this project. We’ve started this with our trustees, and then sequenced out to start to talk to those who are closest to us in the community, as we’re in the early quiet phase of our campaign. So, we are currently in this quiet phase, which we do anticipate is going to last through groundbreaking once we get to around 75 to 80% of our project goal. And we anticipate raising, as I said, 75 to 80% of the funds during this time at least. And this is a consistent message we have to communicate to our board and our constituents, who are very eager to go public, but we’re talking quite a bit about the value of this quiet phase.

Going back to the checklist for a successful campaign, we’ll touch on how each of the key elements have played out at San Diego Museum of Art. The case for support that we have was informed by our feasibility study findings, but it’s really evolved, especially over the past year. Our case is intended to speak to different audiences. And in fact, we have developed several different cases that really address different overarching themes we have for our campaign and expansion. The case is really intended to introduce the museum to the community and the distinct needs that we have at the facility. The needs and the challenges of a hundred-year-old building are really the foundation for our case. And beyond that, we’re looking to inspire folks talking about impact in different areas. So, for those folks who are really looking to have greatest impact through education and youth, we’re emphasizing that for particular audiences.

For others who are really focused on the care of our permanent collection, we’re focusing on that. So, there’s a few different iterations that we’re working with. Strong leadership is really essential, as both Aashika and Lauren have shared. As I’d mentioned, we’re really fortunate to have Roxana Velasquez as our executive director. And she brings tremendous vision for the project that we’re doing. She’s really inspired our board and our community to be behind this project. We’ve also spent a lot of time thinking about how to engage our board meaningfully and understand the process that we’re doing.

We haven’t had a campaign at this museum in more than 40 years before now, so we’ve had to spend a lot of time really educating our board about what it means to have a campaign, why are volunteer leaders so important in this process, and what does that really look like. And so, it has taken us a while to build out a group of volunteer leaders from our board and the broader community. And I think now we have a really inspired, motivated group in place, both our campaign cabinet and the larger group of volunteers who are helping move this forward. We have spent quite a bit of time in the feasibility study and early planning phases in sequencing and prioritizing our prospect list. Lauren can speak more to this, but we have an extensive database with a lot of information that’s really provided the core for a lot of the work that we’re starting to do now.

Lauren Ekmekjian:

Yeah, I’m happy to share a little bit about this. I mean, on the next slide, it sort of articulates this process visually. But if we’re thinking about the process of predictive modeling and prospect prioritization, we sort of start large and filter our way down. And in the case of SDMA and many of our partner clients, we have a lot of names in our database and we just can’t quite start to identify how we pull out some of those key prospects. So predictive modeling and prospect prioritization is a way to start to do that. So, at SDMA, we started with the entire pool of constituents, and we went through both a predictive modeling exercise based on scoring constituents based on their demographic giving and interaction-based data.

So going back to kind of the idea around the RFM analysis, we were assigning weights to different characteristics and qualities. And from there, we screened our top households for their estimated wealth and giving capacity and assessed those results, so that we could see, okay, who are currently our most engaged and generous donors, but also who in our community maybe is giving at $100 a year but has a tremendous amount of wealth or is giving elsewhere in the San Diego community? It helps us start to tear out and assess our results so that we can segment and better prioritize our top households. So, this is just an illustrative example, but it helps to just visually show how we start with all of our constituents in the database. Maybe we identified a smaller subset based on wealth screening and our model scores. And then we kind of parsed it out based on those prospects or individuals and households that could give at a certain capacity. In this case, we were looking at a capacity of $100,000 over five years or more. And from there, we took a look at age and having a strong inclination or existing relationship with SDMA, and we tiered out those two audiences. A tier one group would be our most, let’s say, prioritized prospects that we want to talk to early and first, having a gift capacity of 200,000 or more over five years, and gave at least $100 to SDMA in the last five years. They’re engaged in some way.

And then we bumped down one additional tier having a gift capacity of 100 to 200,000 over five years, and gave a gift to SDMA in the last year. And it really helped us sort out just a sea of information and start to build a roadmap to our early conversations with prospective supporters.

Aashika Patel:

Lauren, can I just add a couple of thoughts here about this predictive modeling? I know in the chat we have some questions about smaller institutions. So, the predictive modeling is really only valuable if you have somewhere north of 7,500 records in your database. So, if you’re a smaller museum, smaller institution, you’re probably not going to benefit from this type of analysis. Something more like an RFM analysis is a little bit more manageable for a smaller database. And then the other thing I’ll note just about this slide here is that the assumption with all of this predictive modeling is that the Museum of Art already knows where its major donors are. Those individuals are giving major gifts to the museum, they are already connected to leadership, they’re trustees, they’re volunteers.

What we are looking for through this predictive modeling exercise is what we call emerging major donor prospects. So, donors who are not giving to you at the major gift level right now but have demonstrated good donor behavior as sort of what the data tells us, and then gives us the signs that we probably are poised to put a major gift ask in front of this individual. So, just two notes I wanted to add.

Lauren Ekmekjian:

I’ll also just add one additional note. Thanks, Aashika. I mean, Stacey. We revert back to this initial work pretty often. So, this doesn’t stay static in time. We did this at the tail end of the feasibility study, and there was a lot of information that we still go through on a regular basis and these lists still evolve. So, if you’re operating at this level with this number of constituents, it can be really helpful, and it lasts over time as well.

Stacey Loomis:

I can jump back in here. So, in addition to prioritizing and sequencing the prospects, we’ve really put a frame around the steps that were needed in the early months of the campaign to get us ready for our first steps and our first solicitations. We spent some time shortly after the feasibility study and in the early campaign planning stages, listing out the specific needs so that we could be really prepared for the critical early asks.

Our timelines have absolutely shifted on this project, and we’ve had to be really nimble and flexible. But the work that we’ve done with solicitation readiness and mapping out our solicitations really helped to offer some specificity and framing around the early months of our work. I’m going to move on to talk about the role of facility tours, which for us and doing an expansion of our historic facility, this has proved to be I would say the most impactful element that we have right now, a really phenomenal tool. Early on, we were using facility tours to show our constituents the aspects of our historic facility that we’ve really tried to hide from the public. And these are the areas that will be directly addressed through our expansion and the new facility that we’re building. This has been especially helpful to us as we have faced challenges in terms of not always being able to show new designs and new drawings. I’m not going to go too much into the detail of this, but we are in a historic cultural park in San Diego and have a historic facility, so there’s a lot of parameters and restrictions around the work we can do.

So, while we’re working closely with our architects on plans, we have to go through many, many stages of approvals and permitting. So, while we’re doing that work, we have to simultaneously be raising these funds. And so, the facility tours have given us an opportunity to really communicate the needs of this project. So, even if we’re not able to show specifically what the solutions look like through the drawings provided by the architects, we’re able to introduce these needs and talk in a grander level about what these solutions will be looking like. So, it’s helping us to cultivate and get folks much readier and closer to solicitation once we have something tangible to share. And in addition to tours, we’ve been working really carefully to leverage important early moments in our timeline. So, we’ve worked really closely across the museum to have some strategic community announcements.

We announced the selection of our architect, which brought a lot of interest to this project, and already brought some prospective donors into the fold just by virtue of the name of the architect that we’re working with. Other early communications, before we had any announcements, we’ve reached out to a wide range, there was probably a hundred phone calls to officials in Balboa Park, in the city, to leaders of other institutions in the community, to talk about what we’re doing so that we could get ahead of this conversation. And we’re really bringing key donors in for various stages throughout this process. So, our architect is working on concept design presently, so we’re finding those key moments to bring prospects in the door to meet the architect. Not to influence the project itself, but to be able to kind of see where we are on this grand level, and to feel that they’re a part of the work from the very beginning of this project.

So, I’ll close by offering a few important lessons we’ve learned. We’ve done our best to build a structure around the campaign and plan, but we’ve also found there have been so many variables and twists and turns along the way that we really couldn’t predict. I’ll mention our merger with the Museum of Photographic Arts as one. That was an unanticipated major institutional advancement, that we’ve now had to incorporate messaging into our plans and think about what our future looks like now that we have another institution that we’re managing. But at the end of the day, we know that our vision is a strong vision. The needs that we have is this institution, the unprecedented growth we’ve had over the past century, has led us to a place where we have no choice but to go forward. And so, we continue to finesse our case, but the needs remain the same. And we’ve found that our donors are responding really strongly to what these institutional needs are.

We’re continuing to engage a broad range of stakeholders, focusing on philanthropy. But we also understand that there’s a lot of overlapping needs in this campaign, and so we need to be communicating with constituents and stakeholders throughout. So, we’re just ensuring as an institution we have clear and consistent communication, we’re being as open and transparent as we can throughout this process. And lastly, really being ready to adapt to a changing landscape, being nimble. Plans will change as you go. And as long as I think you have a strong vision to hold onto, you will get where you need to be. I’ll turn it back over to Aashika to wrap us.

Aashika Patel:

That sounds great, Stacey. Thank you. I know there are a number of questions that came in in the chat. We’ve got a good 20 minutes here to kind of dive deeply into some of them, so I’m happy to do that now with the team.

Tiffany Gilbert:

Great webinar. I just highlighted a few questions. One is, how can smaller museums implement these strategies?

Aashika Patel:

Sure, it’s a great question. Everyone in the world of major gift fundraising has to start somewhere. And so, if you’re a smaller institution, don’t think about your top-level gifts as million dollar commitments or $500,000 commitments. Think about your top-level gifts in the context of your current landscape. So, if the largest gift you’re raising as an institution right now is $10,000 a year, what does it look like to move that number north and start to create donor opportunities for $25,000 or $50,000 where you can sort of start to increase and introduce a new type of prospect to your fold?

The other piece of information I’ll offer is campaigns of all sizes take place every single day. So, we’re working with organizations that are doing campaigns of 5 million or $10 million. And these are smaller, of course. But for an institution that’s embarking on this work for the first time, it’s a really big lift. And so, we recommend the resources that I dropped in the chat as kind of a starting place to think about building a pipeline, engaging your leadership around ideas and conversations for growth, and starting where you’re at. Lauren, I saw you come off mute.

Lauren Ekmekjian:

Yeah. I just want to reinforce that at any level, regardless of campaign size, those four elements can root you and what work is needed, the case for support, your leadership, whether that looks like your existing trustees or a small group of folks to make sure the campaign happens, a timeline to make sure that it happens, and a good list of individuals that you know want to have a conversation with. We’ve done campaigns of 100 to 150,000 that are really rooted in those four elements, and if you can nail those, then you can be successful. So, we really do rely back on, let’s call them pillars, of a strong campaign.

Tiffany Gilbert:

Next question, does the balanced expectation change based on the size of the campaign? It seems it would be more critical the larger end campaign, for example 1 million versus 100 million.

Aashika Patel:

Sure. It does play a role in your overall pathway to goal. But campaigns are fundamentally major gift initiatives, and the goal is to get to your fundraising benchmarks, get through them as quickly as possible. You don’t want to be in perpetual campaign. Part of these efforts require a sense of urgency in the narrative and in the language in order for donors to think about their best and sort of largest gift possible in a relatively short period of time. And so, we would still want you to, even if you’re considering a campaign of let’s say 5 million or 10 million, really think about putting together a table of gifts that breaks down what your top level gift would look like.

So, on a campaign of 5 million or 10 million, you need at least a million dollar or two and a half million dollars gift at the top of that table in order to avoid being in sort of this long campaign period. And then you want to sort of map that out and build a plan around that. I want to be clear and say that there are organizations that pull off extremely large campaigns where the median gift is $100,000 or $150,000. So, it is possible. But you have to start to think about how many people it requires in your donor pipeline in order to hit that goal in a reasonable amount of time, how much staff time that’s going to take, and additional resources it’s going to require. And so, we have found that in sort of the building of campaign infrastructure and mapping, from a major gift standpoint, that we want to take a look initially at that table of gifts, figure out what our largest gift needs to be on that table in order to hit the goal in a reasonable amount of time, and then pursue gifts at the top of that table.

Tiffany Gilbert:

Thank you. Next question. Construction costs went up more than 40% from the time we started planning our campaign and now, when we are about to move to the public phase and begin construction next year. Any advice on how to talk with major donors about the increase and the need for more foundational support prior to public launch?

Aashika Patel:

Sure. So, transparency becomes an important factor in these types of conversations. We’re working with several museums here in Southern California, and as you can all imagine, the cost of building in Southern California never becomes less expensive over time. And so, part of our messaging, part of our narrative is to explain to prospective donors that the reason we’re pursuing urgency, the reason that we need to get these dollars sooner rather than later, is because our project costs are going to grow if we start and then cannot finish on time. And so, communicating this to donors with transparency, making it clear that additional costs are not the result of imprudent spending and other things so that there isn’t a narrative that starts to take shape, being proactive in communicating that.

I generally find that donors, they’ve all sort of built houses and been through construction projects of their own, so they can understand what an institution is going through. But there is an expectation from the donor landscape that organizations are thinking ahead about these potential costs. They’re mapping campaigns, especially capital campaigns, maybe over a five-year period, with the understanding that there’s going to be added costs that grow over time. And so, organizations have the responsibility to be forecasting some of this information and transparently sharing it, of course in a measured and calibrated way, with your prospective donor audiences is.

Tiffany Gilbert:

So, a couple of these questions you might be able to answer together. So, one, why is the quiet phase important before launching publicly? And how did you keep the campaign quiet given public permitting hearings?

Aashika Patel:

It’s an excellent, excellent question. The term silent phase is so misleading. So, we are not silent about the project. An institution should be excited about its next chapter and what it envisions for that growth. And so, sharing plans broadly is completely fine.

It’s almost necessary to bring prospective major donors into the fold. The one thing that you want to be silent about during the silent phase… Two things, actually. The first is how much you’re trying to raise. And the reason being, linked to the previous question, costs can go up, project can change. And so, we want to avoid going out to the community with a number, then changing that number down the line. And so, by the time you transition from your silent phase to your public phase, there will be a universe of donors, let’s say 200 or 250 prospects and some portion or percentage of donors from that prospect list, who know the number that you were pursuing in the silent phase. And then more broadly, the number that will be communicated is the number you go public with.

So, you want to be silent in the silent phase about the overall goal, gives you the flexibility to adjust that number upward or downward based on timing and the needs. And then the second thing we want to be silent about is sort of, and when I say silent, I mean in a public way, you have to communicate this with your key stakeholders of course, is the timeline. So, we don’t want to lock ourselves as an institution into an amount and a timeline if we haven’t already made significant progress towards those goals. And so, the silent phase really allows you to do that before campaigning for this effort more broadly.

Tiffany Gilbert:

Okay. I have another two questions that I’m going to combine because it feels like they would go together. So, you mentioned a feasibility study a few times. Can you define what you mean by that and give some concrete details as to what constitutes a feasibility study? And also, did you have a master plan in addition to the strategic plan and feasibility study? If so, how did it work into the timeline for the project?

Aashika Patel:

Sure. I’ll take the first half of this, and then Stacey, I’d love to turn it over to you because you sort of went through the feasibility study process and have that experience from a different vantage point. From the CCS lens, we believe that some type of feasibility study or pre-campaign planning study is necessary before embarking on a campaign or announcing institutionally, even among your board leadership, that you’re approving and moving forward on a campaign. Reason being is that this pre-campaign planning effort, this feasibility study effort, is going to show you the pathway to reaching your goal. It’s a targeted effort, it’s strategic in that it builds stakeholdership and builds consensus just based off of how that scope of work is designed.

Your feasibility study or your pre-campaign planning study can last somewhere between three months all the way up to five months, so it’s not an incredibly long period of time. But it allows you to test some ideas, bring people who are likely going to be major donors to the effort into the project early before anything has been approved, so that you can build consensus with them and really give them the opportunity to speak into the process. Stacey, I’m curious to hear your thoughts, and then also the question related to master planning.

Stacey Loomis:

Yeah. Well, speaking to master planning, we did not have a master plan at SDMA. We had a strategic plan in place before embarking on the campaign feasibility study. But I’ll also mention, we’ve had a few fits and starts with planning and expansion prior to this. So, Roxana Velasquez has been with us about 13 years. I think there were two conversations in which the board was really engaged on a potential expansion. And we did in fact a feasibility study on the building itself and on the museum’s campus. So, we’ve been engaging with the larger community about this, but not in such a specific, deliberate, and intentional way as we are now.

Tiffany Gilbert:

Thanks, Stacey. So, I’m trying to combine a couple of questions. Trying to get some of them answered. So, here’s another two. How do you convey the cost of fundraising for the campaign as part of the gift? And the other question is if you have donors suggesting estate gifts, life event dependent, how does this fit with a capital campaign that is set up as time dependent? Haven’t done a full study, but this appears in our situation to be the dominant capacity versus available cash capacity.

Aashika Patel:

Yeah. Lauren, if it’s okay with you, I’ll take that first question, and I’ll turn the deferred gifts question over to you. It’s really important to build a campaign budget that correlates with your campaign goal. It’s going to cost money to raise money, especially in the major gift realm. But the cost to raise a dollar in the major gifts universe should be relatively low.

So as a rule of thumb, at CCS, when we’re thinking about campaign goals and we’re testing them in the feasibility study process, we generally find that expenses to raise that amount of money are somewhere between 8 to 12 cents on the dollar. And so, for every dollar you’re raising, you have to expect that you’re going to spend somewhere between 8 to 12 cents to raise that money. And your budget should be broken out accordingly.

A certain amount of money dedicated in a line item to staffing, to events, to travel, everything you’re going to need to facilitate a major gift effort. And generally in that cost to raise a dollar formula, your heaviest line item is going to be staffing. Because we know factually that in raising major gifts, the most expensive piece of that equation is the time, the staff time at the executive level that goes into relationship building and briefings and cultivation and stewardship. And so, definitely start with a budget.

Think about the cost to raise a dollar for any campaign that you’re forecasting in the future, dollars you’re trying to raise over and above, and work from there as you think about making investments to raise those dollars.

Lauren Ekmekjian:

Yeah, I can weigh in on planned gifts. This is really topical for our experience at STMI, so maybe Stacey can weigh in too. So, the incorporation of planned or deferred gifts is a decision that you make with your campaign cabinet or committee, and build that into your policies and procedures. I will say that oftentimes, especially in the case of specific cash needs, there’s almost two campaign goals that we’re thinking about internally in the quiet phase. There’s the broader campaign goal.

In the case of SDMA, there’s an endowment component to this campaign. So planned gifts have a strategic advantage for the museum because we’re not counting on those to benefit our project needs. But further down the line, these deferred gifts are going to play a significant role in the financial future of the museum. But when we’re talking about the actual project needs, we’re remaining mindful of what are the cash needs? What’s the timeline for those cash needs? And how are we thinking about in sequencing our prospects to have the right conversation at the right time about a planned gift and/or a cash gift?

And I will say, for some of our most generous prospects, Stacey, we’ve approached them with what we would call a blended gift request. So, considering something like a cash gift or a pledge over time in coordination with considering an estate gift alongside that cash gift. And we’ve been I would say successful at closing some of those blended gifts where we know that we have a cash component built up front that’s going to be paid over the next three to five years, but we’ve also built in an element for the endowment in the future. And we’re capturing all of that in the campaign total, in what we’ve raised. Stacey, anything to add to that?

Stacey Loomis:

I think coming up with strong policies around planned giving has been really essential. What are the age minimums to count gifts? What are the dollar minimums for certain giving vehicles? So, this has been an ongoing discussion that we’ve been having. And as Lauren said, with SDMA, the planned gifts are really supporting the endowment component of this campaign. I will say, while we are raising funds for this overarching expansion, we do have cash needs along the way, and this has come up. We have a timeline with our architects and other partners and real needs for cash. And so, we have been able to go back to those donors who have made planned giving commitments and to be, I think, pretty transparent that we have these cash needs. Would folks consider giving a portion of that gift as an outright cash donation? These are conversations that I anticipate will continue as we move forward with this campaign.

Tiffany Gilbert:

I think we have time for a couple more questions. In your experience, does it take a donor pool of 10,000 to yield 250 major prospects? We have an active donor pool of about 2000. Does this mean that I should expect 50 major prospects if we conduct analysis on our donor pool?

Aashika Patel:

Great question. It’s very difficult to draw conclusions between the size of a database and how much capacity is in that database. Because you could have a donor database of 10,000 records, but no strong relationships within that universe of 10,000. Or you could have a database of 2000 records and be an organization that has a very strong culture of relationship building and a great loyalty within that database. And so, it’s difficult to draw a correlation just based off of the size. You would need to do a little bit of analysis of the quality of those records inside the database. And so, I’d probably ask the question slightly different, which is that if you are looking to raise X amount of dollars and you go ahead and map out that table, we need this many gifts at a million dollars, this many gifts at 500, this many gifts at 250, cascading from the top. So, you’re going to have the fewest number of gifts at the top.

You’re not going to, if you’re doing a $10 million campaign, have ten $1 million gifts, even though we would all love that. Generally it’s going to be the case that you might have one gift at 2.5, one gift at a million, several gifts at 500,000, even more gifts at 250, even more at 100,000. So, you want to really build out that table and take a look at, okay, how many gifts am I going to need to hit this target? And where could these gifts come from based off of the relationships I have in my database? And so, I encourage you to think about it that way, instead of just the size of your database correlating to an outcome.

Tiffany Gilbert:

And although we did get a whole lot of questions, I’m going to ask one more. Again, for all of the attendees, we’re sending all these questions to our panelists, and they’ll be able to review them and hopefully send us back responses and we’ll add it to the website. What about raising endowment funds along with a capital campaign?

Aashika Patel:

That’s a really great question as well. We typically find there’s a certain profile of donor that is interested in giving endowment gifts. Foundations are not often big fans of endowment giving. And so, there can be a strategic opportunity in launching a capital endowment and endowment campaign, if you think about something Lauren mentioned earlier of deploying a strategy with a dual ask for all your major donor prospects, a cash ask of a gift you’re looking for to be paid within the next two to five years, and then some kind of deferred gift component, so a planned gift. And the cash gift can go to your capital project dollars you need today for a building or otherwise, and then the deferred gift can go to your endowment to really build the endowment over a long period of time.

We are seeing a trend, even in capital campaigns, of thinking a little bit about a building endowment. So whatever dollars you’re investing in a future space or a new space, it’s going to require resources to keep that building up. And so is it a good idea to just establish a fund, an endowed fund, to support the building? We’ve been seeing a lot of interesting projects in that vein as well. Lauren?

Lauren Ekmekjian:

Yeah, I was just going to reinforce, part of our case at SDMA is to talk about the endowment as part of our financial viability into the future. So we’re building this beautiful building with the cash needs, but we need the endowment to be there and financially viable into the future to support the additional operational costs. And for the right donor, that’s a really compelling and I would say sustainable way to talk about fundraising at your organization. And I think it’s played well, Stacey, especially with our trustees who want to know for the next 100 years, we’re going to be in a strong financial position.

Stacey Loomis:

Also add, we have some of our major donors who are very close to us who are not really supportive of building projects. And they want to support the endowment. They have already shared this with us. We are giving them that option, even cash gifts, not planned gifts, going to the endowment. So I think this is a conversation we have to have. While we do need cash now for this project, we need to meet our donors where they are, and the endowment needs are very much a real and important part of this expansion project.

Tiffany Gilbert:

Thank you, Aashika, Lauren, and Stacey. You hit it out the park again. Great job. Wonderful webinar. Lots of engagement in the chat, and I’ll be sure to send that to you. But to everyone on the call, thank you so much for attending our third webinar of the AAM Financial Wellness Web series. You’ll receive a follow-up email with links and resources. And we look forward to seeing many of you in Baltimore this May for AAM 2024. Thank you all. Take care.

Stacey Loomis:

Thanks everyone.

Comments