After I asked my husband to repeat himself multiple times in one conversation, he eventually turned to me and said, “You don’t hear anything I say. Please get your hearing checked.” I balked at his request and suggested that he speak “louder” and “clearer.” Hearing loss is not something one would experience in their thirties, right?

Fast forward some months, an otolaryngologist, and two audiologists later, and I found out that hearing loss can be experienced at any age. While age-related hearing loss, also called presbycusis, typically starts around age sixty-five, according to the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders (NIDCD), that doesn’t mean it can’t affect you when you’re younger. My doctors confirmed my hearing loss was bilateral, and the cause was probably genetics. They suggested I try hearing aids.

According to NIDCD, 15 percent of the US adult population (37.5 million people) experiences some degree of hearing loss, and about 3.6 percent (11 million) are Deaf or have “serious difficulty” hearing. A third of people between the ages of sixty-five and seventy-four have hearing loss, and nearly half of people older than seventy-five do. Despite the size of this population, we are often underserved in many ways. It might surprise you, for instance, (as it did me!) that most health insurance in the US does not cover hearing aids or implants—even though mild hearing loss could be linked to double the risk of dementia, per this John Hopkins study, and is more common than diabetes.

As you may have heard, April was National Deaf History Month. But one month is not enough time to celebrate any community, so this article is a tribute to museums celebrating the Deaf community year-round. I wish to make this article a call for members of the museum community to consider how we can all acknowledge, welcome, include, and celebrate the Deaf and hard-of-hearing community. Here are some ideas from your peers to get you started.

Access to Exhibitions through Technology and Tours

New-York Historical Society emphasizes the importance of accessibility and proper accommodations for Deaf and hard-of-hearing visitors, especially through technology. This includes basics like providing open captions, film transcripts, and t-coil access for audio and video. In addition to this, the museum recently upgraded its auditorium to an FM-assistive listening system. “Our goal is to make the experience of visiting New-York Historical as seamless as possible for visitors who are Deaf or hard-of-hearing,” says Nick Mancini, Vice President of Visitor Services. “We’re always looking towards the latest technology that can remove or reduce any barriers to entry and enjoyment of our exhibitions and collections.”

Tours in languages other than English are a key component of accessibility. With some advance notice, New-York Historical Society can also provide an ASL interpreter to accompany adult and school tours on a complimentary basis. Katy Menne, Education Director at Columbia River Maritime Museum in Oregon, says her institution has started offering tactile, smell-o-vision, and ASL tours. “We wanted to be able to offer learning in other languages. I’ve had experience with incorporating ASL into my previous museum, so we hired an interpreter, published the event, and waited to see what happened. One family drove about three hours to come for the tour and were so excited that it was offered.”

Incorporating accessible practices into exhibitions is also an opportunity to involve Deaf children. In 2020, The Children’s Museum of Indianapolis received a three-year Museums for America grant from the Institute of Museum and Library Services that allowed staff to redesign the museum’s Dinosphere® exhibition and make it a more accessible and inclusive experience for families, especially those with a child with a disability. Museum teams and an advisory group of accessibility professionals worked together, resulting in the addition of ASL best practices to the exhibit. “Staff continue to apply those lessons, working through the best ways to integrate ASL into new projects and exhibitions,” says Betsy Lynn, Accessibility Coordinator.

Creative Programming for the Deaf Community by the Deaf Community

Expanding access to your current exhibitions and programs is important, but so is creating new ones specific to the Deaf community—with the community’s involvement. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, for example, trained a cohort of Deaf educators in art-based tours, gallery-based learning, and other education initiatives, many of whom they continue to work with to develop programming for the Deaf community. Over the years, this programming has included a variety of ongoing tours: An Evening of Art & ASL, a social setting for the D/deaf community that includes refreshments and discussions of art; Met Signs Tours, exhibition-related tours presented in ASL by a Deaf educator with no voice-interpretation; and Met Signs in the Studio, a tour and artmaking program in which the participants head to the galleries for a tour and then move to a dedicated art space to begin to respond to the art they just experienced creatively.

One recent example was “Met Signs in the Studio—Richard Avedon: MURALS,” in which a group engaged in a tour of the exhibition before going behind the scenes to participate in a photography workshop and photoshoot. According to Emily Harr, Program Associate, and Rebecca McGinnis, Senior Managing Educator, Accessibility, “The group was inspired by the political nature of the exhibition and focused their shoots on messaging relating to Deaf President Now [a 1988 protest to appoint the first Deaf president of Gallaudet University], Deaf awareness and culture, and anti-audism.”

Invest in Hiring Deaf Individuals

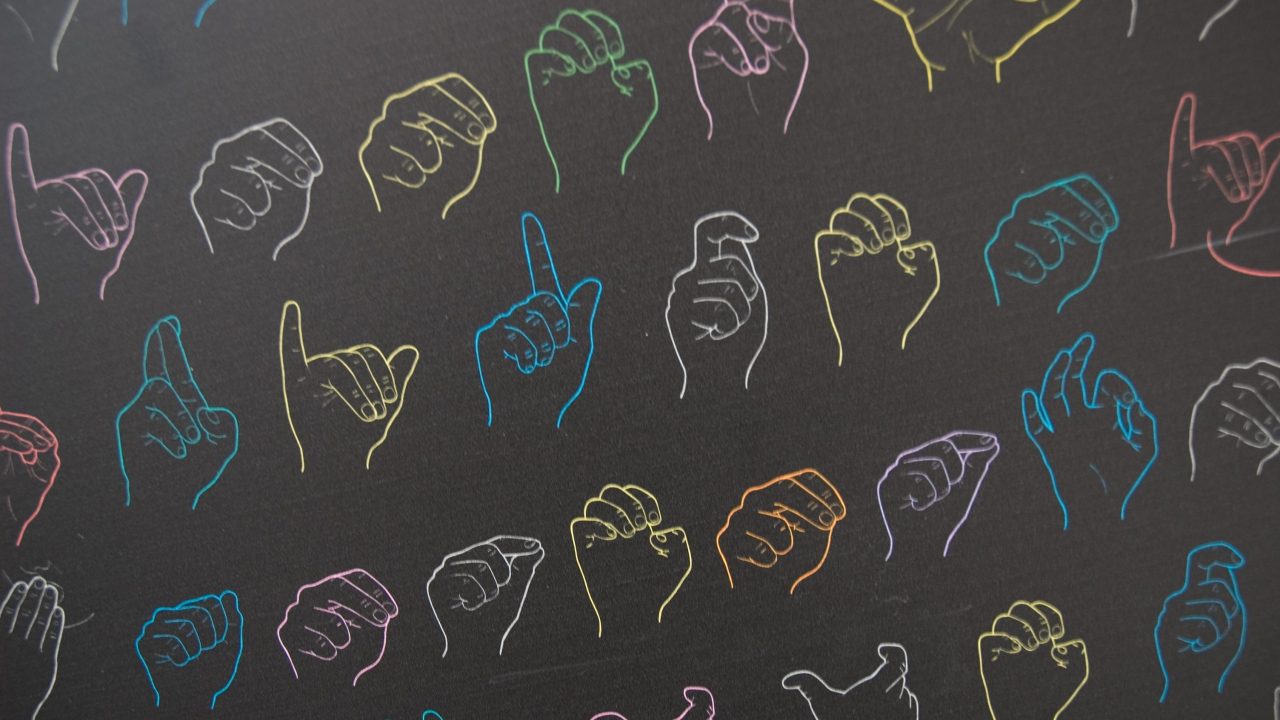

In his twenty-eight years working at The Met Store, General Manager Luis Feliciano says hiring a Deaf employee, Snezhana, was one of the best decisions he’s ever made. He cites her work ethic, attention to detail, and contributions to the team. He also cites the profound effect on The Met Store’s culture. “By being part of our team, Snezhana has enriched our workplace culture and fostered a greater sense of inclusivity and empathy among us,” says Feliciano. “Her presence serves as a reminder of the importance of embracing diversity and celebrating our differences.” This motivated Feliciano to launch an ASL training program for the Met Store team, which launched at the beginning of National Deaf History Month. “It became evident that effective communication is crucial for our team’s success and for fostering an inclusive and welcoming work environment. I wanted to ensure that all team members have the ability to communicate effectively with each other, regardless of any barriers or differences.”

As he says, there are good reasons to embrace disability inclusion beyond just doing the right thing. A report by the professional services firm Accenture showed that organizations which do this have greater profitability and higher returns to shareholders. Companies with employees with disabilities enjoy more innovation, improved productivity, and a better work environment. On a more macro scale, employing a mere 1 percent of the disability community could boost the GDP by twenty-five billion dollars.

Provide Equitable Support for Deaf Staff

Where do you start if you want to hire a Deaf employee? You can team up with organizations like Job Path or AHRC, which provide job support and other services to people who are neurodivergent or have other developmental disabilities, such as hearing loss. An experienced organization can help you identify the right job candidate and even provide onboarding and training support. This is the path The Frick Collection took when it hired Luis Peña, a member of the museum’s housekeeping team.

It’s not enough to hire someone Deaf. Giving them equitable support is paramount. For the Frick’s Chief Human Resources Officer, Dana Spencer Winfield, communication is the main component of this equitable support. “Engaging with Luis resulted in our realizing that if you really want to have an inclusive workplace, you have to provide people access through communication. We realized we needed to start having ASL at meetings, which we do.” The Frick now brings in an interpreter for all meetings, including social events. Winfield adds, “This past year, we heard from the staff that they wanted more facetime with our director and senior leadership. We started having casual lunches. When Luis came to those, we made sure there was ASL.”

When I ask what he would recommend to museums that want to bring a Deaf staff member onboard, Peña tells me, through an interpreter, “Interpreting services would encourage Deaf people to work in an environment that offers it.”

The Frick’s large-scale community events offer ASL interpretation, CART captioning, and assistive listening devices. The museum hosts programs specifically for the Deaf community, and will continue to work with accessibility consultants to expand and improve program accommodations. It has also decided to prioritize hiring staff members who can serve as a liaison between the museum and its Deaf and hard-of-hearing visitors. The museum has promoted Leonard Charles-Titus, who is a child of deaf adults (CODA), to serve as Assistant Manager for Visitor Services and Access. He says most Deaf individuals are “elated and start chatting with me. ‘Are you Deaf?’ and I’m like, ‘No, I’m not Deaf. I just work here.’ They’re like, ‘Oh, this is so nice that they have this.’”

Embrace the Challenges with Cultural Competency Training

There are many challenges that come with being the only Deaf member of an all-hearing team. “Communication can get twisted,” says Peña, referring to how facial expressions involved in ASL can be misinterpreted by hearing individuals. Still, despite these challenges, when I ask how he likes working at the Frick, compared to the eight other jobs he had prior, he signs, “I love it here.” He expresses his desire to keep learning and working.

The Frick is an example of how, rather than shying away from challenges that arise, you can use them as an opportunity to train staff so that your company culture is reflective of the values you want to instill. “We’ve had many trainings with the Mayor’s Office for People with Disabilities about how to communicate successfully with Deaf people,” says Winfield, for example. She describes these trainings as eye-opening experiences. “Sometimes the knee-jerk thing for people who are hearing is to shout, like English speakers often do with people who are non-English speakers. They think that shouting is going to help. It’s not,” she explains. “So just remembering to tap Luis on the shoulder if you want to get his attention, touch his shoulder, touch his elbow, wave, do the lights on and off, speak to him slowly and directly so that he can, if he chooses to, read your lips. We’ve tried to educate the staff around all those different ways of communicating with people who are Deaf.”

American Sign Language (ASL) Training for All Staff

Most of the museums in this article have been involved in some form of formal ASL training and are leveraging that training to connect with the Deaf community. In the past, New-York Historical Society offered ESL and Spanish language classes to employees, but in 2024 the choice was ASL. It was “an easy decision…as it works towards many of our goals for staff professional development,” says Mancini. The Met provides Spanish, French, Italian, and ASL online courses as part of its professional development offering. This is in addition to the ASL training offered to The Met Store staff. “I strongly urge other museums to start ASL programs as soon as possible,” says Feliciano. “By doing so, museums demonstrate their commitment to inclusivity and embracing collective differences. ASL programs not only benefit Deaf or hard-of-hearing visitors, but also create a more welcoming environment for all visitors.”

For the Frick, ASL is part of a long-term strategy. When the museum reopens to the public later this year following renovations, it plans to unveil a revamped visitor experience to match. “One of the things that we’ve talked about is doing a very intensive, immersive ASL class for all of our forward-facing staff,” Winfield says. “That means all the visitor services, visitor experience people, anyone who works in the museum shop, anyone who works in security, so that if we have Deaf visitors come visit the museum they can be greeted verbally with voice, but they can also be greeted with ASL.”

There’s a lot to be said about learning your visitors’ or teammate’s languages. “In addition to ASL, I encourage museums to embrace all languages spoken by their team members,” says Feliciano. “At our Met store, our team members speak over twelve languages, which contributes to a diverse and inclusive atmosphere. This diversity enriches the visitor experience and promotes a sense of belonging for all visitors, regardless of their language or background.”

When I ask Peña, at the Frick, how he feels about his colleagues in ASL classes coming to him and signing, he lights up: “Proud.”