If working at a big art museum taught me one thing, it is how unexpectedly diverse visitor groups can be, both culturally and linguistically. As a museum educator with a thick accent myself, I prefer to get ahead of the questions and ask my group first: “Does anyone here speak any language other than English?” The responses usually take me on a proverbial trip around the world: from Spanish and Arabic to Amharic, Ukrainian, Yoruba, and Tagalog.

As public-serving institutions, museums welcome visitors with a wide variety of primary languages through their doors. Some are tourists visiting the country, some recently immigrated and are still learning the dominant language, and others might have been born in the country but raised in a different cultural and linguistic environment. Especially in the United States, where one in five people speaks a language other than English at home, it is imperative to consider English language learners (ELL) in public programming to foster an atmosphere of inclusion and belonging.

But how do you consider them, given that no museum team has enough resources to hire bilingual educators covering all possible languages? What should you do in a common situation where you have a group of mostly fluent English speakers but one or two people still learning the language? As someone who speaks four languages myself, has a degree in linguistics, and immigrated to the United States as an adult, I have wrestled with this question over the years and worked out a set of tips and strategies for an inclusive and engaging gallery experience for English-learning visitors.

In this article, I will share five key tips from my experience, using K-12 students as an example because it’s the demographic that I work with the most. However, I believe these strategies will be useful for any age and any type of public programming. Corresponding with the principles of universal design, these tips aim to create an inclusive and welcoming environment, accommodating all visitors. Not just those who speak other languages, but also those who might have different learning styles or levels of familiarity with the subject of a museum.

1. Provide clear instructions.

Skip over related stories to continue reading articleTry to be straightforward and direct when it comes to providing instructions, whether ways to respond to your prompts or rules to follow in the galleries. Don’t be afraid to use your hands in the process—most gestures are universal and carry similar meanings across different cultures and languages, but some are not, so be mindful.

Try not to rely on idioms or colloquialisms, as students who haven’t had prolonged school experience in the United States yet might not know the meaning of using “walking feet” or keeping voices at “levels zero or one.” Explain the instructions literally while modeling them for the group to visually illustrate your requests.

2. Offer different opportunities for response (and be patient!).

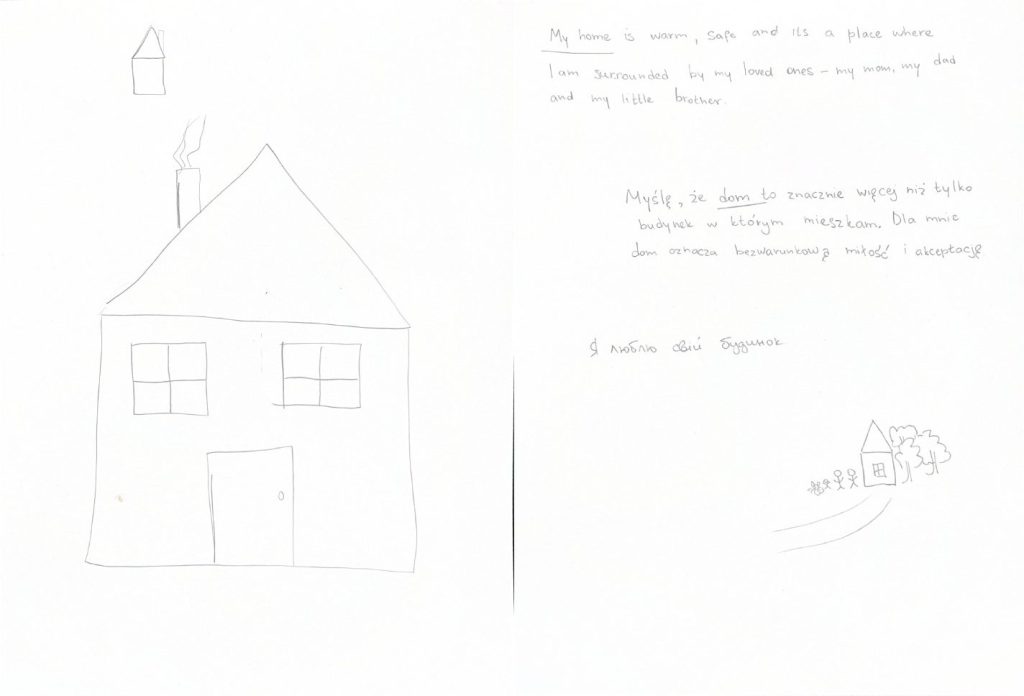

Give your visitors a choice in how they want to respond to your prompts. For example, you could offer them to write their thoughts in any language, draw a sketch, silently reflect on their own, or find a neighbor and have a small group discussion out loud.

Encourage the group to take their time in responding and incorporate that wait time in your tour plan. English language learners may need extra time to process the question, frame the answer, and then translate their thoughts into English before responding.

Keep in mind how cultural differences might influence the responses you get. In some cultures, long silence is seen as a sign of respect and appreciation or as an opportunity to gather some thoughts, whereas in US norms it is often seen as uncomfortable or a sign of lack of engagement and interest. It is the same with asking and responding to questions: Depending on the cultural norms, questions can be encouraged or frowned upon. Consider those differences and build extra time into your programming for processing and responding.

3. Reinforce key vocabulary.

Don’t be afraid to repeat the main points of information throughout the program. Even if a word or concept seems obvious or familiar to you, it could be new for your visitors. If you introduce a key term, such as the name of an art style, a movement, or a type of material, always provide the definition. If it’s a new word for English language learners, they can use your explanation to understand what you mean and connect it with a word in their primary language.

In addition to conveying the content of the program effectively, this can also be a good opportunity for vocabulary learning. For example, I only learned the word “kite” at the age of twenty-seven, because I grew up flying a kite in a different language.

4. Overexplain context.

Sometimes people who grew up in a different language and cultural environment won’t understand references to historical events, personalities, or trends that might be considered common knowledge in the United States. Don’t automatically presume that background information is widely understood—instead, take the time to lay out relevant contexts simply and clearly.

Even if some of your visitors are already familiar with the subject matter, providing that framing can reinforce learning and ensure everyone is on the same page. I’ve found that giving a brief overview of the time period, the key figures involved, or the cultural significance can unlock so much more engagement and insight from English learners than when you skip this step.

5. Limit pop culture references.

It is easy to slip in references to TV shows, celebrities, slang, or other pop culture phenomena without a second thought. But those kinds of casual references can unintentionally create barriers for some English language learners by drawing on contexts they may not be familiar with.

For example, I once worked at an exhibition that featured a statue of a big purple dinosaur. My colleagues kept mentioning the name Barney, and I had no idea what they referred to. Even now that I’ve learned more about famous American children’s characters, I continue to find pop culture references more exclusionary than relatable, since they can limit opportunities to feel engaged and belong.

As with other aspects of context, try to avoid making assumptions about shared cultural knowledge and using culturally specific examples or analogies. Instead of making the references in passing, try asking the group if they have seen something similar before. This can open an enriching dialogue without accidentally alienating visitors who come from a different cultural and linguistic environment.

As a docent at a zoo, I found this to pretty helpful, but I wish there were more examples. And, it’s really hard to know what someone doesn’t know! And equally hard, for example, to explain EVERY cultural icon that some in your audience might not know. I would think you’d run the risk of alienating the locals if you take time to explain EVERYTHING!

Great point, Pamela! I think it’s all about finding a balance between providing enough context and making sure people don’t get bored, but it’s always important to consider the different life experiences of visitors who come through our doors. Thanks for sharing your thoughts!

Really loved the content. Not taking for granted the “usual” references is always important.