This is an excerpt from TrendsWatch: Museums as Community Infrastructure. The full report is available as a free PDF download.

“Ageism is a prejudice against our own future selves and takes root in denial of the fact that we’re going to get old.” —Ashton Applewhite, author and age-activist

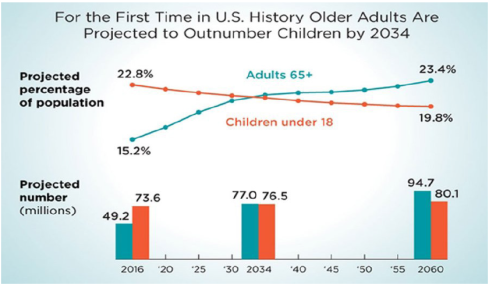

By 2030, one in five Americans will be over the age of sixty-five, and in some states that figure will top one-quarter. By 2034, older adults will outnumber children in the US population. As the AARP has pointed out, in the past seventy years our primary focus, as a society, has been on meeting the needs of families with children. This focus has shaped every aspect of our lives, from the design of buildings, transportation systems, and neighborhoods to the policies behind zoning and human resources. The unintended result has been the creation of physical and social systems that isolate and marginalize people as they age. This separation is unhealthy for people of all ages. Younger people are deprived of valuable wisdom and expertise, as well as role models for their future selves. Isolating older people from society creates grave risks to their mental and physical health. Museums can play a vital role in creating “age-friendly” communities that support physical activity, social connection, and intellectual stimulation, as well as providing pathways for elders to contribute to their communities and to following generations.

The Challenge

A woman born today in the US can expect to live to be eighty-one years old, a man seventy-six, and those averages are rising with time. Though Baby Boomers (born between 1946 and 1964) have long expressed their intent to work until age sixty-eight, the COVID-19 pandemic has impelled a wave of early retirements, meaning many people face a decade or more of “post-work” life, while continuing to want opportunities for meaningful engagement and to give back to their communities. This stage of life is not without challenges. Even though the Age Discrimination in Employment Act protects people age forty or older, those who want to remain in or rejoin the workforce often face discrimination in hiring and on the job. Forty percent of people over the age of sixty-five have some kind of disability—whether that involves mobility, cognition, hearing, vision, or barriers to independent living. About 20 to 25 percent of older adults have mild cognitive impairment, and about 10 percent experience dementia (though that rate seems to be falling over time).

Regardless of underlying health or ability, everyone who lives to grow old in the US at some point joins the ranks of people subject to the pervasive, corrosive bias of ageism, a form of discrimination that itself contributes to depression, cognitive decline, ill health, and (perversely) a shorter life span. And ageism combines with other “isms”—racism, sexism, homophobia, and class prejudices—to create a toxic brew of intersectional damage.

It is increasingly common for older Americans to face these challenges without a network of family or social support. In the US, 27 percent of adults over the age of sixty live alone (more than double the figure for adults age twenty-five to sixty), and social isolation has a negative impact on health as severe as smoking up to fifteen cigarettes a day. Older Americans are also much less likely than their counterparts elsewhere in the world to live in a household without young children, which contributes to generational isolation as well, denying children access to the care, mentoring, and role modeling that can be provided by older adults. The safety net woven by family relationships will fray even more in coming decades, as the US birthrate drops. In 2010, there were, on average, seven potential caregivers for every senior. The AARP expects this number to drop to four by 2030, and to fewer than three by 2050. Nearly 90 percent of Americans over the age of fifty want to “age in place.” However, the lack of family caregivers, and the absence of any nationally funded and organized substitute, will make it difficult for people to remain in their own homes rather than moving to assisted living facilities. In any case, by the end of this decade, 54 percent of seniors will not be able to afford either assisted care or independent living, precipitating crises in both housing and health.

Meanwhile, we’ve created communities and environments both online and in real life that seem almost intentionally designed to make it hard for elders to remain actively engaged with the world. Only 1 percent of housing stock in the US features universal design elements such as no-step entrances, single-floor layout, and space designed to accommodate wheelchairs. Some developers create “senior communities” for people over a given age, ranging from housing co-ops to entire suburbs. Though these environments may address challenges of physical accessibility and social isolation, they can become “age bubbles” that isolate residents from a richer spectrum of community assets. The internet can, theoretically, connect the housebound to the world, but it comes with its own set of challenges, as digital design often features illegible text, tiny icons, and other age-unfriendly features.

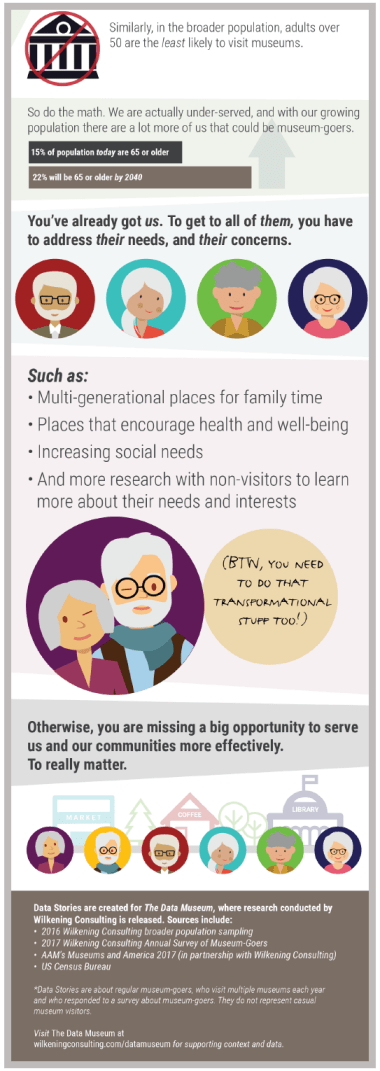

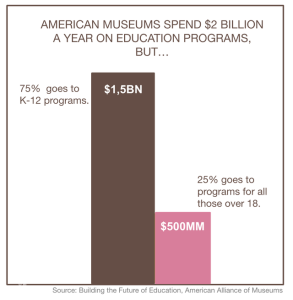

Museums have room for progress in becoming age-friendly as well. Though there is a widespread assumption that older individuals are among the most frequent visitors to museums, research shows the opposite to be true. In the US, fewer than a quarter of people age sixty or older visit a museum in any given year. (Older adults may seem to make up a larger share of the audience because those that do go to museums tend to be frequent visitors.) Many aspects of traditional museum design are age-hostile, including the lack of seating, sensory overload, and barriers to physical accessibility. Even museum programming can add to generational segregation, if older people are funneled only towards offerings (like passive lectures) that museum staff believe they will want.

More than 60 percent of people over the age of fifty-five engage in some sort of volunteer activity, formal or informal, and the opportunity to volunteer is one of the major benefits nonprofits provide to society. Copious research documents that volunteering helps individuals expand their connections, feel good about themselves, improve their physical well-being, combat social isolation, reduce stress, and learn new skills—benefits that are particularly helpful in supporting healthy aging. In museums, volunteers typically outnumber staff by a factor of six to one, performing a wide range of work including stocking the gift store, preparing research specimens, working as greeters, planning and running fundraising events, and giving tours. However, the benefits afforded by volunteering are often not equitably shared with a museum’s community. Historically, the corps of museum volunteers have skewed towards older adults with the time, inclination, and financial resources that enable them to volunteer. As a result, their demographics typically mirror that of museum personnel (both staff and board)—which is often disproportionately white, well-educated, and relatively well-off. Volunteerism can exacerbate inequality if, as in many museums, it is only accessible to people who are already comparatively privileged.

The Response

In Society

There is growing consensus that the most robust solution to the isolation of aging is to bake better design into the landscape and infrastructure of towns and cities. In 2006, the World Health Organization introduced a framework for age-friendly cities that encompasses eight domains: health care, transportation, housing, social participation, outdoor space, respect and social inclusion, civic participation and employment, and communications and information. As of 2017, over five hundred cities around the world had signed on, pledging to make their communities better places to grow older, and AARP has worked with WHO to extend this practice to 207 communities in the US. As is invariably true of inclusive design, creating age-friendly communities is good for everyone—increasing access to employment, arts and culture, critical services, community participation, and affordable housing. As AARP points out, “Age-friendly communities foster economic growth, and make for happier, healthier residents of all ages.”

In Museums

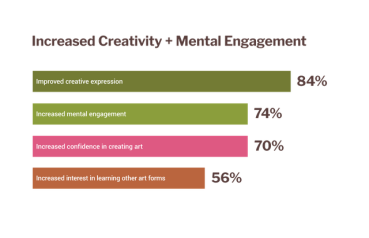

Museums play many roles in making communities age-friendly as places of social connection, employment, mental and physical engagement, and as influential forces in combatting ageist stereotypes. Since the early 2000s, museums have helped fuel the creative aging movement—using the power of arts engagement to foster healthy, active aging and improve the lives of older people. Research from the Seeding Vitality Arts initiative of Aroha Philanthropies documents that sustained, meaningful arts engagement supports healthy aging, increases the self-confidence and mental engagement of participants, and fosters social connections.

Museums also step in to meet the needs of the many people experiencing health-related challenges as they age. Programming specifically designed for people with dementia and their caregivers has been shown to reduce levels of depression and improve cognitive functioning and overall quality of life. Engaging with art through viewing, making, and movement can help people coping with Parkinson’s disease or other debilitating illnesses to maintain their mobility and social connections.

Museums are also an important component of age-friendly communities regardless of the specific programs they offer. Recent research shows living in a community with various cultural resources confers a five-year advantage in cognitive age, with museums and similar cultural organizations providing the biggest boost to cognitive health. (However, that benefit is skewed by race, with Black populations experiencing less protective benefit from museums, pointing to the need to improve equitable access to museum space.)

The museum sector is still searching for a good model to reconcile the tensions that sometimes arise between volunteers (often older individuals) and paid staff. Some of the approaches being tried include creating a long runway (even a decade or more) to implement structural changes in volunteer programs, and including volunteers in the process of addressing DEAI and social justice goals. Others focus on creating an organizational culture, backed up by appropriate procedures, that foster a volunteer corps that is diverse with respect to age, race, and other elements of personal identity.

Museum Examples

Fostering Age-Friendly Design

Recently, the Design Museum and the Design Age Institute launched a project to establish a new infrastructure for collaboration and co-creation around design and aging. Designing a World for Everyone will bring together researchers, designers, innovators, and policymakers to share the latest research and insights into how design can be used to transform public spaces, cities, and communities to support the aging population. Associated programming includes The Wisdom Hour, a creative storytelling space celebrating positive stories of aging, facilitated by This Age Thing. Over the course of a year, the project will place local community groups at the heart of the decision-making process, respond to the needs and concerns of underrepresented groups, and create social impact by removing and reducing barriers to participation.

Cultivating Social Connection

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the Musical Instrument Museum (MIM) in Phoenix partnered with Arizona State University to create virtual programming for senior communities who could not visit the museum in person. The initiative produced two Senior Wellness video series, one for active seniors and one for people in memory care. Teams of music therapy students from ASU developed music therapy interventions that complement virtual tours of MIM’s galleries, with a focus on physical skills (drumming, dancing, and other movement), cognitive skills such as attention and memory, and psychosocial components related to self-expression through music.

Creating Intergenerational Connections

The Museum of Contemporary Art in Tucson’s Stay Gold program supports the intergenerational LGBTQ+ community, connecting generations through creativity and making and using contemporary art to explore relevance and meaning in the lives of the participants. In 2018, older adults from Stay Gold proposed creating an intergenerational version of the teen School of Drag performance. Local drag performers taught the workshops and a youth drag performer emceed the show. During the pandemic, museum staff adapted the Stay Gold programming to an online format, offering artmaking prompts inspired by LGBTQ+ artists to maintain the connection so badly needed during this time of heightened isolation. This work was supported by a Seeding Vitality Arts in Museums grant from Aroha Philanthropies.

Cultivating Creative Aging

In 2016, Aroha Philanthropies launched a major multi-year initiative, Seeding Vitality Arts, to foster creative aging programs in a variety of settings, including museums. In 2018, the American Alliance of Museums partnered with Aroha Philanthropies to support a museum-specific cohort through Seeding Vitality Arts in Museums (SVA), providing twenty organizations with training and resources to develop and implement high-quality, intensive arts learning opportunities for older adults. The resulting programs included an Expressive Movement workshop at the Anchorage Museum building on Indigenous knowledge and lifeways; “Viva la Vida” artmaking at the National Museum of Mexican Art; and traditional drumming and Mardi Gras beading at the Louisiana State Museum. When the COVID-19 pandemic forced museums to close their doors, leaving elders at even greater risk of isolation, the SVA museums reinvented their work to engage with participants over remote platforms. The Olana State Historic Site, for example, remastered its plans for a place-based eight-session playwriting workshop. Kicking off with a virtual tour of the historic house, participants spent more time on research using digital documents, and seven professional actors read the finished student scripts over Zoom.

Meeting the Needs of Older Audiences

In 2014, noting that only 3 percent of older adults in New York City visit senior centers, the Museum of Modern Art created the Prime Time Collective, a diverse group of adults ranging from sixty-one to ninety-four years old, to help identify and address financial, physical, informational, and attitudinal barriers to participation in museum programs. In the past decade, the museum has partnered with community organizations to offer specialized programming for LGBTQ+ older adults, individuals and caregivers coping with Parkinson’s or Alzheimer’s disease, and for teens and older adults to come together (for example, the 2016 program Act Your Age). In collaboration with the Martha Stewart Center for Living, the museum launched a “social prescription” program, in which physicians and social workers can write a prescription for art programming at MoMA. For housebound seniors, the museum offers online programming in partnership with the Virtual Senior Center.

Supporting Older Adults with Dementia

Since 2010, the Frye Art Museum has partnered with the Alzheimer’s Association and the Seattle nonprofit Elderwise to develop and implement participatory arts experiences for people living with dementia and their care partners. In the ensuing decade, the museum has fostered a large community of practice by offering professional development to individuals engaged in similar work, and conducting research that adds to the growing body of literature documenting the contribution of arts engagements to healthy aging. One of the signature programs of this effort is the annual Creative Aging Conference, an interdisciplinary exploration of topics related to art, creativity, and aging.

Explore This Future

Signal of Change:

A “signal of change” is a recent news story, report, or event describing a local innovation or disruption that has the potential to grow in scope and scale. Use this signal to spark your thinking about how museums might support age-friendly communities in the future.

Creating an Age-friendly City

In 2021, the Purposeful Aging Los Angeles Initiative (PALA) issued recommendations to advance its goal of making the Los Angeles region “the most age-friendly in the world.” One of the recommendations is to make all tourist attractions and buildings in the Los Angeles region age-friendly. “As new building construction occurs (and buildings are updated over time), it is critical that they provide welcoming, functional environments for all generations. This is especially important for stadiums, museums, studios, convention centers, major public facilities, and other tourist attractions that draw a high-volume of visitors, including older adults. The County and City will partner with these institutions/facilities, as well as the Los Angeles Tourism and Convention Board, USC School of Gerontology, and other partners to develop a ranking system for major regional tourist attractions. We anticipate generating awareness of, and attention around tourist facilities that have taken steps to become age-friendly.” (Emphasis added.)

Explore the implications of this signal:

Ask yourself, what if there was more of this in the future? What if it became the dominant paradigm? Write and discuss three potential implications of this signal:

- For yourself, your family, or friends

- For your museum

- For the United States

Critical Questions for Museums

- What aspects of conventional museum design and operation pose barriers to access for older audiences?

- How can museums elevate the power, voice, and status of older individuals, helping to create a culture that honors, values, and empowers elders?

- How can museums promote the creation of age-friendly communities and integrate themselves into a seamless network of support?

- How can museums make volunteer opportunities accessible to a broad diversity of older individuals?

- How can museums address ageism in the steps they take to promote diversity, equity, accessibility, and inclusion in their own work cultures?

- How can museums shift older adults from the group least likely to use museums to one of their biggest audiences?

- How might museums bolster their own sustainability by serving older adult audiences better?

A Framework for Action

To help create age-friendly communities, museums can:

- Inventory barriers to access or use. This might include physical barriers (including stairs, ramps, handrails, and restrooms), comfort (including seating, acoustics, lighting, and readability of signage), cultural or social barriers (including attitudes and behavior of staff and ageism reflected in marketing, exhibits, and programming), and transportation (including availability and location of parking and access to public transportation). Ensure that digital design is age-friendly as well.

- Provide age-equitable opportunities for employment and volunteering. Consider training managers and human resources staff on how to avoid ageism in hiring and employment, establishing a working group of paid and volunteer staff to identify how to value and support older volunteers, including age and ageism in the museum’s DEAI plans and policies, and addressing age-related stereotypes and assumptions in DEAI training.

- Assess how older adults are represented in your content, from exhibits to marketing, and work to ensure that elders are both seen and valued.

- Identify older adults in your community who are “culture-bearers” and give them platform, power, and authority to transmit the knowledge, experience, skills, and stories that they care for.

- Design programs and services that actively foster intergenerational connections: In addition to creating rewarding relationships, dialogue between older adults and youth has been shown to be an effective tool to reduce ageist attitudes and behaviors.

Additional Resources

- Museums and Creative Aging: A Healthful Partnership (AAM, 2021). This report, authored by Marjorie Schwarzer, opens with an overview of aging and ageism in our country, documents actions being taken to foster positive aging, profiles the work of museums providing creative aging programming, and shares lessons learned from the Seeding Vitality Arts in Museums initiative, funded by Aroha Philanthropies, now known as E.A. Michelson Philanthropy.

- Age-Friendly Standards for Cultural Organizations (The Family Arts Campaign, 2017). These standards are designed to help cultural organizations provide a welcoming and positive experience for everyone, regardless of their age, and to facilitate intergenerational interactions.

- Global report on ageism (World Health Organization, 2021). This report outlines a framework for action to reduce ageism for use by governments, the private sector, and civil society organizations, and includes a toolkit for the Global Campaign to Combat Ageism.

- The Old School Anti-Ageism Clearinghouse is an online compendium of free resources to educate people about ageism and help dismantle it. It includes information about and links to blogs, books, articles, videos, speakers, and other tools (workshops, handouts, curricula, etc.) accessible to the general public.