As part of the Alliance’s current Next Horizon of Museum Practice project, CFM has been highlighting stories of museums trying to redress the cumulative historical effects of harm to Indigenous communities, including damage to mental and physical health, capital, education, property, and cultural heritage. Today on the blog we share an interview highlighting the careful and collaborative approach the Clyfford Still Museum brings to this work.

Elizabeth Merritt, VP Strategic Foresight and Founding Director, Center for the Future of Museums

Building partnerships with groups historically excluded from museum spaces is often problematic because of institutionalized power structures, traditions of harm, and systemic barriers. So how can museums—historically extractive by design—shift their practices to empower these groups through restorative action?

That’s the question that has guided the Clyfford Still Museum (CSM) in Denver as it has worked alongside representatives from the Confederated Tribes of the Colville Indian Reservation in Washington State to bridge regional and cultural divides, using the Museum’s collections as the starting point to build community, foster authentic connections, and open reciprocal pathways for communication.

What follows is a shared telling of the initiative’s origins by Bailey Placzek, CSM Curator of Collections and Catalogue Raisonné Research and Project Manager, and Michael Holloman, enrolled Colville Tribal member (sńʕaýckstx/Lakes) and Associate Professor of Art and Coordinator of Native American Arts Outreach at Washington State University. The text functions as a dialogue between our voices, with initials indicating who is writing when.

Background

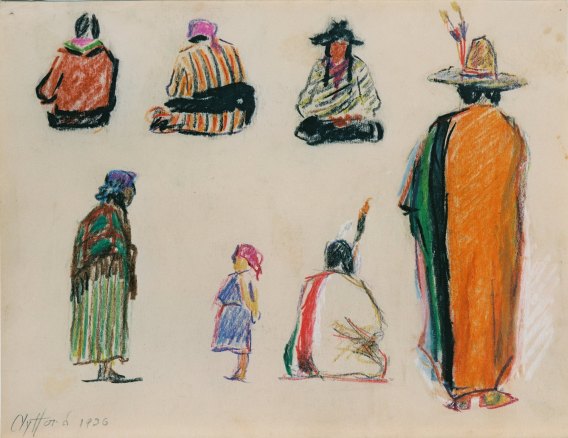

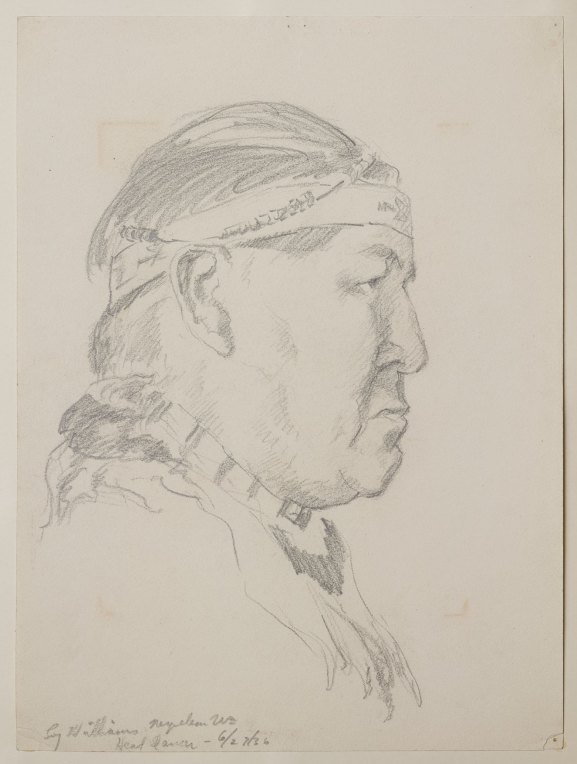

Bailey Placzek (BP): American abstract expressionist painter Clyfford Still (1904–1980) spent three formative summers in and around Nespelem, Washington, on the Colville Reservation as a young art instructor at Washington State College (WSC [now Washington State University]) between 1936–38.[1] While there, Still assisted in founding the Nespelem Art Colony for WSC community members and students. He paid minimal sums to Tribal members to sit for portraits and led a variety of classes for program participants. CSM has three paintings on canvas, more than eighty-five drawings and sketches on paper, nearly twenty documentary photographs, and other archival ephemeral objects documenting his time and the people he met in the area (many of whom he identified by name with inscriptions).

In 2021, CSM began developing You Select: A Community-Curated Exhibition, which highlighted various communities that influenced Still during his life, including the Colville Confederated Tribes. As part of this exhibition’s development, CSM reconnected with Michael Holloman, who had previously been in touch about CSM’s opportunity to engage the living descendants of the individuals Still depicted in his portraits and the larger Colville Tribal community.[2] You Select opened a pathway to explore that possibility through object interpretation.

Big Idea

With the support of our new director, Dr. Joyce Tsai, and alongside CSM’s former archivist, Erin Shafer, I was eager to learn more about the historical context of our collection materials, meet the family members of the individuals in the Colville artworks, and potentially uncover new information and perspectives about this body of work. However, Holloman encouraged us to step back from any predetermined outcomes or timelines and focus on open-ended in-person introductions that could lead to long-term collaborations. Acknowledging that Still’s own association with Colville was transactional—like that of so many other white artists working in Native communities at the time—we sought to revive a relationship with the community that would be reciprocally generative instead.

Michael Holloman (MH): In the past, authority has rested with museums, which have too often dictated to Tribal communities what was needed and what could be gained by collaborative partnerships.[2] Here, we sought to structure our engagement around laying a foundation for the Colville Tribal community to present to CSM what they envisioned important outcomes might be for a partnership, so Tribal members could participate and be recognized in their own history.

This emphasis on self-determination is crucial for engaging with Native tribes, who have historically fought for their sovereignty and right to assert agency over their own culture and shape their history, representation, health, and homelands. In fact, at the same time Still paid members of the Colville Confederated Tribes to sit for portraits, the Tribes were working to do just this, establishing a council of Tribal leaders to replace a federally appointed Indian agent to oversee their affairs.

BP: We designed an itinerary to visit the reservation that focused on laying the groundwork for possible future conversations. Rather than focusing on deliverables and deadlines, we dedicated the trip to introduction, listening, and sharing, understanding that building a trusting and open relationship would take time.

Holloman connected us with John Sirois (sʔukʷnaʔqín/Okanogan sp̓aƛ̓mul̓əxʷəxʷ/Methow ps’quosa), the Colville Tribe’s Traditional Territories Advisor, to arrange visits to the Tribal agency headquarters, Colville Tribal Museum, and the surrounding Nespelem area. Planning our trip with an appointed representative was critical to our success. Sirois and Holloman also helped us understand and ensure we followed appropriate cultural protocols and etiquette.

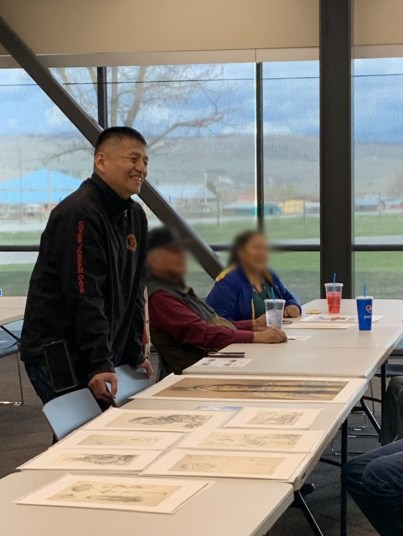

Sirois reserved a large meeting room at the Lucy F. Covington Government Center in Nespelem, where we could facilitate an open-house-style gathering. We provided him with a list of the families of people Still depicted in the 1930s, and he invited any relatives still living in the area to stop by the government center during a three-hour time block. As the descendants came in, we introduced ourselves, gifted them with high-quality reproductions of artworks and archival materials connected to their relatives, and showed images of related works from our collection to encourage discussion.

We opened the conversations by emphasizing that we were there to introduce ourselves, share our resources, learn about the descendants’ history, and listen to their reasons for engaging with CSM. These open-ended, unrecorded conversations provided space for residents to reflect upon their own personal experiences with their family members or places depicted in Still’s artworks, without fear or uncertainty of how the CSM would use their recollections. (They also revealed that some of the information in our collections records was inaccurate.)

Reflection

“The drawings bring out personal experiences that people can remember; they give us a sense of our history.”

It was moving to watch people look at the reproductions of portraits we brought and recognize family members. Diedre Williams (wal’wáma/Chief Joseph Band of Nez Perce) was particularly emotional upon seeing the young face of her grandfather. She shared her memories with us and was excited to learn she could take the reproductions home. Later, she graciously recounted her memories for our use in You Select:

“I remember my grandpa sitting in his chair as I stood behind him watching our favorite show, Superman. It was on one of those old black-and-white TVs with long antennae. Back then we lived very modestly but wanted for nothing.”

We left Washington with an overwhelming sense of objects’ power to connect people across cultures and time. I gained wholly new perspectives on Still’s works after experiencing the place and context of their creation—matching the lines of Nespelem’s hilltops to his colorful landscape studies and envisioning streetscapes as they looked nearly a century ago. Our departure also brought the fragility of these relationships into focus; how could we truly hold ourselves accountable to this place and its people as museum representatives, given the weight of past harms?

Back in Denver, we reexamined our current collections practices, assessing how our outward positions on “authority” and “access” were inwardly demonstrated through internal data management standards. Whose perspectives on an object were we treating as critical, and thereby worthy of entry into our collections management system? When we experienced these objects in their original context outside the museum’s galleries and storage rooms, they helped foster collective memory, a sense of belonging, and joy. How could that be translated into our cataloging policies?

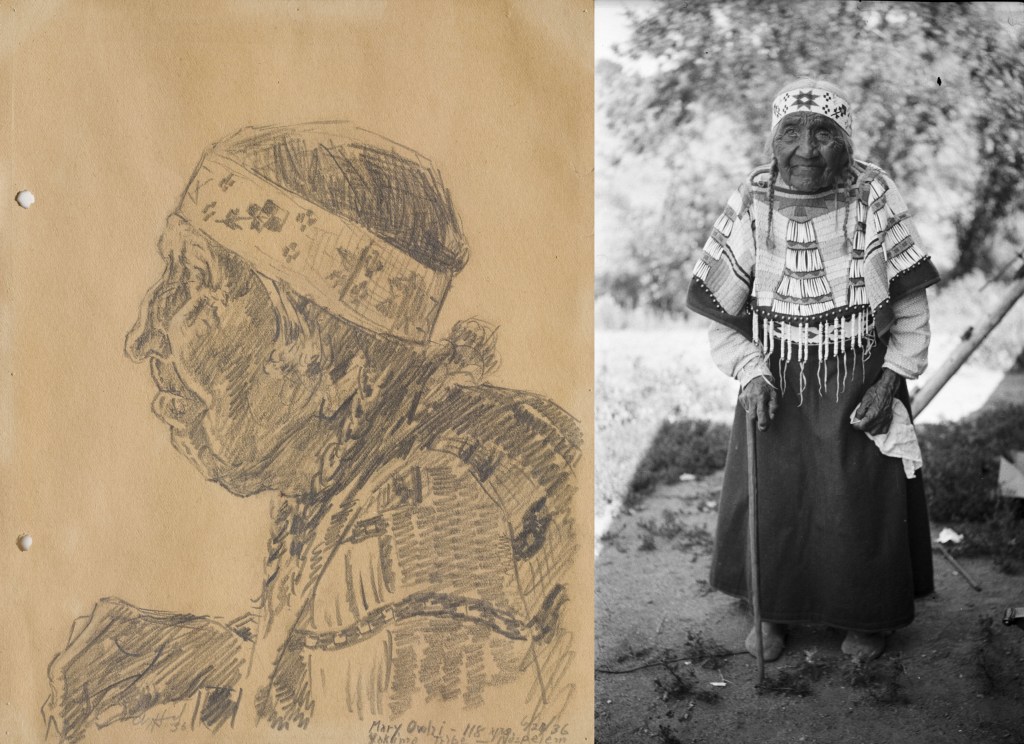

Right: Negative of Mary Owhi. Photograph by Clyfford Still, c. 1936. Courtesy the Clyfford Still Archives

MH: Sometimes individuals and institutions change only when they are forced to, given no other options but to respond to changing times and requirements. But nonetheless, this pressure to change can afford genuinely transformative opportunities. Committed individuals can inspire an organization to shift their actions through their own devotion to change. My relationship with CSM initially began with my participation in a single public program but has grown over the years. The work that started there has blossomed into an institution-wide initiative over a long period of time.

Federal Indian policies of relocation and the establishment of rural reservations away from non-Native communities have created a physical and cultural divide. Museums, in turn, are challenged to create and strengthen relationships with Tribal partners to help bridge those divides. This requires commitments of time and treasure. Direct, face-to-face encounters are crucial to developing healthy relationships and habits. We are used to relying upon technology to bridge vast distances, but it cannot replace direct communication within one’s museum or with Tribal communities.

BP: This project broadened our institutional priorities beyond simply hitting deadlines and deliverables. We slowed down, became open to the project’s evolution, and redefined what success meant to us. It was challenging to come to terms with the idea that we may not have any concrete results or answers to present after the trip, but it also opened up possibilities for the future. CSM leadership’s unwavering support for this open-ended approach has been crucial.

“What’s next?”

BP: After our visit, we invited Colville Tribal members to visit CSM in Denver. Later that fall, we hosted a panel discussion with Shafer, Sirois, Holloman, and me to introduce the initiative to our own local community. During the visit, Sirois, Holloman, and visiting Colville resident Jewie Davis (wal’wáma/Chief Joseph Band of Nez Perce) saw Still’s original artwork and archival materials. Later that evening, we asked them, “What’s next?” They looked at each other and expressed a desire to extend our partnership to Tribal youth. Now, more than three years into the initiative, we have returned to the reservation three times at the invitation of our advisors to pursue these goals and are excited to share outcomes in upcoming posts on this blog.

MH: In subsequent visits to the reservation, CSM offered opportunities for Tribal members and government representatives to address the harms of the past and to interrogate the Museum’s intentions for this partnership. The Tribal Council and the broader community, however, were more interested in developing relationships that could benefit their communities in the future. We will outline the details of those partnerships in our upcoming posts.

With patience and a professional willingness for structural change, building collaborative networks with Tribal communities offers tremendous benefits for museums. I recently witnessed the repatriation of a Chilkat blanket and other cultural objects from the Northwest Museum of Arts and Culture in Spokane, Washington, back to the community of its origin in Southeast Alaska. During a transfer ceremony at the museum, a Tribal elder (Yanÿeidí) emphasized the need to recognize that the museum is now part of the blanket’s living history. He said that the museum’s role in its story is not just about colonial extraction and appropriation, but also its commitment to restorative work. These commitments are what can, over time, shrink the distances between seemingly disparate communities.

BP & MH: CSM does not possess any Tribal cultural objects, particularly those that would necessitate federal repatriation responsibilities. Yet beyond the framework of NAGPRA, there exist other models museums can use to create meaningful partnerships and empower Indigenous communities. When CSM staff first traveled to Nespelem in 2022, it was an important step towards the museum’s investment in a shared relationship with the descendants of Still’s sitters from the Nespelem Art Colony in the 1930s. CSM does not see this partnership as a discrete event but a starting point for a living, reciprocal future, bridging past and present into a shared artistic celebration for all.

Authors’ note: Stay tuned for future posts about our collaborations with Colville Tribal youth and the Colville Children Curate (title TBD) exhibition opening in September 2025.

[1] While culturally distinct and diverse, the twelve bands of the Confederated Tribes of the Colville Reservation include the Chelan, Chief Joseph Band of Nez Perce, Colville, Entiat, Lakes, Methow, Moses-Columbia, Nespelem, Okanogan, Palus, San Poil, and Wenatchi. The bands share cultural practices and 1.4 million acres of land in northeastern Washington.

[2] CSM first engaged Holloman during the development of Clyfford Still: The Colville Reservation and Beyond, 1934–1939, which was installed at CSM from May 8–September 13, 2015, and was accompanied by an exhibition catalog of the same name. Curated by scholar and art historian Patricia Failing, this installation was the museum’s first (and only) exhibition dedicated to Still’s Nespelem artworks. Failing conducted extensive research in the Coville area as part of her research and we are indebted to her foundational study of Still’s Nespelem works.

[3] One of the main intentions of the 1990 Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA) was to encourage continuing dialogue between museums and Indian Tribes and Native Hawaiian organizations where none previously existed.