The unexpected closure of the Museum of Art at the University of New Hampshire shocked staff and supporters—and offers important insights for the field.

This article originally appeared in Museum magazine’s September/October 2024 issue, a benefit of AAM membership.

Museum directors are experts at managing risks of all kinds. The American Alliance of Museums (AAM) requires every accredited museum to have a disaster plan. At the Museum of Art at the University of New Hampshire, located in Durham, our disaster plan ran more than 165 pages and was housed in a three-inch-thick, three-ring binder. It detailed responses to fire, theft, environmental damage, biological hazards and chemical spills, power outages, flooding, and hurricanes.

I have been in this field long enough to have lived through financial crises, facility emergencies, accidents, disputes with collectors, and entanglements with artists’ attorneys. However, despite my prior experiences and our diligence in maintaining the disaster plan, we were not prepared for what would happen on January 16, 2024, when the university closed the Museum of Art and laid off all four staff members.

When disaster struck, I and my staff made the best decisions we could at the time. While I hope no one finds themselves in this awful situation, the experience, though unique to academic museums, revealed personal and professional insights into the lead-up and process of closing a museum.

The Immediate Aftermath

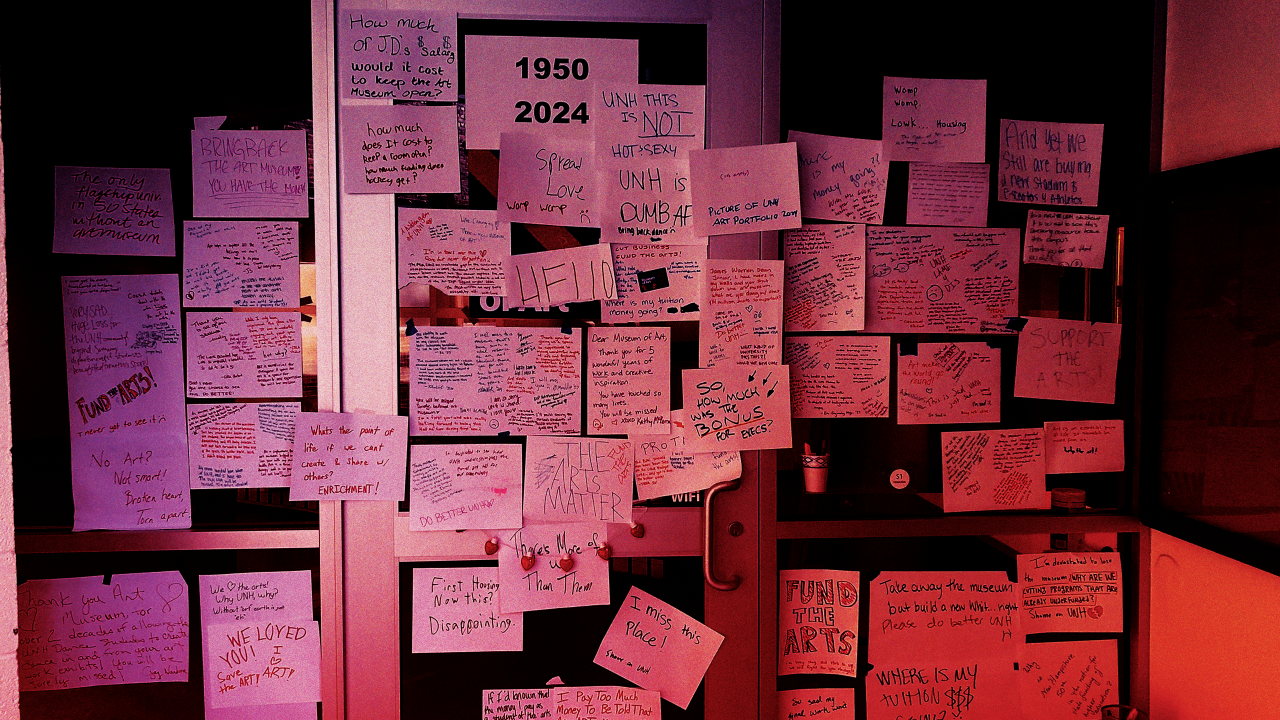

In response to declining enrollment, the university undertook a “budget reset,” resulting in a $1.4 million cut to the College of Liberal Arts and the Museum of Art’s closure. As news of the museum spread, my inbox was inundated with messages from bewildered patrons, students, and faculty bemoaning the staff layoffs and urgently asking, “What can I do?” I received copies of letters that people sent to university leadership, thoughtfully arguing in support of the Museum of Art, which was founded in 1941, and its storied history on campus as a place to learn from studying art up close and in person. Many supporters recounted transformative experiences as undergraduates, while others wrote about exhibitions and programs that enriched their lives as members of the local community.

This outpouring of letters, posts on social media, messages, and phone calls encouraged me and my coworkers. The calls for me to be reinstated and staff to be retained indicated the genuine connection we had with faculty and patrons, but the university administration was unwilling to revisit its decision.

That our terminations happened during the winter break when students and faculty were off campus was no accident. Other than a forum for faculty of the College of Liberal Arts, the administrative home for the museum, the University of New Hampshire never publicly announced the Museum of Art’s closure. This left me as the primary contact and spokesperson for inquiries from the media and public, including donors, artists, and alumni, all of whom were wondering what would happen to the museum’s collection. We were left wondering, too. We were completely taken aback by the decision and had no closure plan, despite our meticulously detailed disaster plan, and no experience to guide us on what to do next.

Once we regrouped, my colleagues and I devised an action plan addressing operations/security, safeguarding the collection, preserving historical documents and collection records, and communicating with the public. Thankfully, the university committed to retaining the art collection, which numbered about 2,500 objects. To ensure the collection’s security, we met with the Department of Art and Art History faculty to develop plans for accessing the collection, maintaining the collection database, and managing backups for high-resolution collection images.

Together we assigned responsibilities to the appropriate staff to oversee distinct tasks: continuing insurance coverage; securing our electronic files and collection management database (backing up and printing hard copies); coordinating transfers of files to archives; checking in with campus security, facilities, and housekeeping; canceling pending gifts and proposed acquisitions; responding to inquiries from members of the public and press; and creating inventories of museum equipment and supplies to be turned over to the Department of Art and Art History. We also worked with the university’s procurement office to unwind or cancel outstanding contracts, loan agreements, and subscription obligations.

Lastly, we developed talking points to use with members of the press who began to contact me after the local paper published a faculty member’s opinion piece about the museum’s closure and layoffs. Our talking points conveyed the university’s decision, though we did not justify the rationale. We explained that museum staff were not consulted, that the decision was a surprise, and that the museum was financially healthy with more than $700,000 in endowment funds and more than $230,000 in current-use funds. Important to us, we also reassured people that the collection would be maintained and that its works would be made available through the Department of Art and Art History.

People have asked if, in retrospect, we had any warning. Were there dark clouds circling above the Museum of Art? Truthfully, we did not have any warning, nor could we have done anything differently. The university’s decision was abrupt and devastating. Nonetheless, the Museum of Art staff responded with professionalism, tact, and unwavering dedication in preserving the museum’s collection and history. Molly Bolick, Education and Communications Manager; Stephanie Garafolo, Exhibition and Collections Manager; and Kathy McKenna, Office Manager, deserve this acknowledgement.

What We Learned

As an academic art museum, we were fortunate to count professional archivists among our colleagues. With the University Archives staff, we developed a plan to preserve the museum’s exhibition and loan histories, ensuring that the collection and donor records would be accessible for research, future inquiries, or retrieval if the Museum of Art should reopen under a new administration. Together, we preserved records and documentation of 60 years of artistic production for future use.

To ensure that a museum’s archives and records are preserved in the event of closure, museums, particularly in small communities, should partner with historic organizations. At small museums, donor records are often retained for legal purposes, but the ephemera generated by exhibitions and public programs are discarded. This is especially true for the digital content many museums generate. Municipal archivists can help develop a retention and preservation plan for museum records.

Two weeks after the staff received their 45-day notice, the dean of the College of Liberal Arts asked us to develop a transition plan for the Department of Art and Art History. When we led faculty on a walk-through and reviewed collection management processes with them (including our integrated pest-management plan), it was clear they were unprepared for the amount of work required to maintain a collection to professional standards.

Communication is another critical component of a museum closure. Staff, board, and friends group members will suddenly find themselves without a role at the museum and will need support. Our staff were notified on a Tuesday that our positions were eliminated and were asked to leave campus for a day or two. Museum staff came back together on Friday to discuss the layoffs and develop communication plans and action steps.

Devise an emergency communications plan so that you, your board, and staff are not caught flat-footed if your museum is shuttered. Whom will you need to contact? Imagine a diagram of concentric circles, with the inner circles comprising the people who are the most impacted. Work from the inside out to notify these people.

We had to notify donors, advisory board members, student employees, artists, and businesses with which we worked. The university did not assist us with this, nor did they assume responsibility for working with donors and patrons. The dean of the College of Liberal Arts spoke to the media to clarify the reasoning behind the closure decision, but many patrons were left wondering what would become of the collection.

You will also need to decide who will liaise with the press after closure. Who will compose the public response, and how will you get the word out? Do you need legal advice before speaking publicly, or will the board chair be the primary spokesperson? Independent institutions will need to notify their secretary of state to legally close. Obtain legal advice before you proceed with dissolution.

As president of the Association of Academic Museums & Galleries and a former member of the board of directors of the New England Museum Association, I was fortunate to have colleagues from other museums write letters of support to university administrators, imploring them to reconsider their short-sighted decision. Others spoke to the press about the Museum of Art’s value and its role in the community. Do not hesitate to rely on the support of your regional and national museum leaders.

Losing not only our jobs but also the museum that enriched the campus and broader community was devastating for all of us. A colleague wrote to me months later, “The museum was not closed—it was abandoned. . . . The university’s failure to take professional and ethical responsibility for the collection, the publications, and the permanent records that make up the museum—that is disrespectful to all staff, board members and artists that were involved with the museum.”

Members of the Museum of Art’s dedicated board of advisors independently met with the university administration to discuss how the university could financially support the Museum of Art and fundraising opportunities going forward. The board of advisors are determined to support the arts at the University of New Hampshire and hold out hope that a future administration will be receptive to reopening and restaffing the Museum of Art. Their determination and willingness to engage in conversations about financial stewardship and sustainability, even in the absence of a museum director, is commendable. I truly hope their efforts are successful.

Sidebar

Know Your Rights

Nobody wants to focus on losing their job, but if it occurs, it will be helpful to know what you are due ahead of time.

Read and understand your organization’s employee benefits. What are you owed for unused time off? What are your expenses to maintain health insurance through COBRA? Are other benefits available from your employer if you are laid off?

The Employee Assistance Program offered by the University of New Hampshire provided eight free mental health counseling sessions. Additionally, as part of the separation, laid off employees could meet one-on-one with a career services adviser, which was invaluable during my search for new employment.

You will also want to research your state’s unemployment benefits requirements and application process. Pass on this information to your staff to help them navigate unemployment. Additionally, write letters of recommendation for your staff, which they can use as references in their job searches.

Resources

Susana Smith Bautista, How to Close a Museum: A Practical Guide, 2021