“The gross national product does not allow for the health of our children, the quality of their education, or the joy of their play.”

Humans are driven to succeed, so we mold our behavior to fit our definition of success. If what we truly want in life is to be happy—and for others to be happy too—that suggests we should measure how we feel. But in government, business, and even our private lives, we usually focus on profit/loss, ROI, net worth—not because money is the most important thing in the world, but because it is easy to quantify and track. Increasingly people (and organizations) are rebelling against this focus on finance, pointing out that it has fostered the accumulation of wealth at the expense of health, sustainability and wellbeing. Governments are experimenting with a variety of nonfinancial metrics, including happiness, and businesses are finding that happiness is actually profitable. Once we redefine success to include more than cash, museums are poised to make sizable contributions to our collective bottom line.

Western society hasn’t always seen cash as the measure of all things. Back in the 18th century, social reformer Jeremy Bentham argued that happiness is the most important metric of life. But happiness is subjective and therefore hard to measure, so over time economists have expediently used people’s expenditures as a signifier of how they experience and value the world. This approach resulted, for example, in the post-World War II emergence of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) or Gross National Product as the primary measure of national prosperity.

But it’s been clear from the beginning that money is a poor proxy for happiness. Back in 1974, a USC professor articulated what became known as the Easterlin Paradox: while rich people are on the whole happier than poor people, national wealth (and higher per capita income) doesn’t make one country happier than another. And our focus on finance has had many unhappy side effects. Measuring only what people spend money on, and therefore what other people earn, undervalues unpaid activities like housework, volunteerism, and time spent doing simply nothing (otherwise known as “relaxing”). It also fails to capture externalities—the costs borne by future generations when profit is made by consuming nonrenewable resources or damaging health or the environment. And it doesn’t capture economic factors like inequality that may violate our collective understanding of what is ethical or fair. Perhaps most troubling, as we face the imminent costs of climate change, GDP, stock value, and other key financial metrics don’t measure sustainability.

There have been challenges to such economic oversimplification for decades. Bhutan got a lot of attention for their Gross National Happiness Index starting in the 1970s. In 1990 the United Nations debuted the Human Development Index, which takes into account life expectancy and education, as well as per capita income. A recent intensification of interest has generated a host of new schemes as well. In 2009 Nikolas Sarkozy, then president of France, commissioned a report from Amartya Sen and Joseph Stiglitz, both of whom are Nobel prize-winning economists, that critiqued GDP and proposed “sustainable happiness” as a key measure of success. The following year France introduced happiness as a major topic in its annual national Social Portrait. (Intriguingly, the French researchers found it is easier to measure unhappiness than happiness, creating a kind of inverse metric of success.) That same year Prime Minister David Cameron made a commitment to developing a General Wellbeing Index for the UK. Across the globe, governments are adopting schemes to weigh the impact of nonmarket goods like employment, health, volunteering, and reduction in crime.

The search for meaningful metrics has infiltrated the business sector as well. In 2010, Zappos CEO Tony Hsieh launched the “happiness at work” movement with his book Delivering Happiness, making the case that happiness in the workplace correlates with employee engagement, retention, productivity and, ultimately, higher profits. Hsieh has even created an ROI calculator (widely adopted by other companies) that quantifies the benefits a business can derive from cultivating happy employees. According to happiness advocate Shawn Achor, these benefits, on average, include boosting sales by 37 percent, productivity by 31 percent, and accuracy by 19 percent. That’s pretty significant when you consider that as of Gallup’s most recent survey, less than a third of Americans are “engaged” with their jobs (i.e., enthusiastic about and committed to their workplace); the level of engagement is lowest among Millennials.

You may have noticed that these various movements and schemes focus on a host of related attributes: happiness, well-being, satisfaction, engagement. The differences between these nouns, while subtle, can be significant. Wellbeing includes a broader measure of health and ability to function and implies a system that values goals other than personal happiness. While most people would grant you can’t have too much wellbeing, seeking to be perpetually, blissfully happy is not a realistic or even a desirable goal. But “happiness” is intuitive and compelling. It grabs the public imagination (cue Pharrell Williams’s 2013 hit song “Happy”).

As with any trend, happiness is now being commodified, with books, courses, and even apps promising to help you attain this elusive state. See, for example, the Happify app, grounded in “science-based emotional wellbeing” and using a proprietary framework (Savor, Thank, Aspire, Give, Empathize) to cultivate resilience, mindfulness and lasting happiness. Sometimes, however, the prescription for happiness is less technology, not more. (The Happiness Research Institute in Copenhagen recently showed that simply disconnecting from Facebook for one week made participants perceptibly happier.)

As with any trend, happiness is now being commodified, with books, courses, and even apps promising to help you attain this elusive state. See, for example, the Happify app, grounded in “science-based emotional wellbeing” and using a proprietary framework (Savor, Thank, Aspire, Give, Empathize) to cultivate resilience, mindfulness and lasting happiness. Sometimes, however, the prescription for happiness is less technology, not more. (The Happiness Research Institute in Copenhagen recently showed that simply disconnecting from Facebook for one week made participants perceptibly happier.)

One of the problems with using happiness as a metric is that until recently, researchers had to rely on accurate (and honest) self-reporting. Now technology is providing new tools to directly measure mood. Bank of America has tested personal sensors that use location data, voice analysis, and motion sensors to track the happiness and productivity of employees. (The pilot data led BoA to deploy a new schedule of lunch breaks that reduced stress and turnover and improved productivity.) Facial recognition software, teamed with artificial intelligence, is learning how to read emotion (e.g., Microsoft’s Project Oxford, as well as products from a slew of small startups, one of which—Affectiva—was recently profiled in the New Yorker). Algorithms can perform sentiment analysis on masses of data from social media to diagnose the mood of groups or regions. Recently researchers have used magnetic resonance imaging to map where happiness emerges in the brain in the hope of developing “happiness programs” based on scientific research.

What This Means for Society

Stay-at-home mothers and wives have been devalued and marginalized for decades because their work in the home is not counted either financially or in its contribution to family well-being. This social devaluation of unpaid work may still be contributing to the gender inequity in time spent on childcare and housework, even in families where both spouses want to make equal contributions. If we do indeed face a future of radically lower employment (see the chapter on labor in this report) and increasing inequality of wealth, it’s more important than ever that we embrace nonfinancial measures of whether a personis a valued, and valuable, member of society.

Credit: Jeff Miller: University of Wisconsin–Madison

Defining success in nonmonetary terms is particularly important for Millennials, who face higher rates of unemployment than peers with equivalent education, and even if employed have no guarantee of economic success: nearly half of college graduates in their 20s are trapped in jobs with low pay and no prospect of advancement. Fortunately, it seems like Millennials have good instincts when it comes to pursuing happiness, preferring to spend their money on experiences rather than stuff, a strategy that has been shown to be more likely to produce lasting happiness.

To the extent the search for nonfinancial metrics focuses on happiness rather than a better-rounded look at wellbeing, we need to be careful about stigmatizing unhappiness (or anything less than euphoria). Facebook and other social media already pressure people to present a prettified version of their lives. A cultural shift to mood metrics may simply mean people lie about their mental state as well as their income, and are more stressed and less happy as a result.

Perhaps most importantly, because we get what we measure, a national or international shift away from short-term financial gains toward subtler metrics that factor in sustainability, health, wellbeing and, yes, happiness, may result in a world that is not just richer but better.

Museum Examples

There are several examples of museums working with hospitals, or hospitals establishing museums, in order to boost patient wellbeing and health outcomes. The Chelsea and Westminster Hospital in the UK was awarded museum status in 2009, and found that after integrating art into the wards, all patients experienced a psychological lift, “27% very much so.” The Al Maktoum Hospital Museum in Dubai used a social media campaign, #wordsthatheal, to create and share an archive of words that “have a powerful and remedial effect on those suffering.”

The Happy Museum Project helps the UK museum sector respond to the challenges presented by the need for creating a more sustainable future. “Happy Museums,” the project contends, “are about building a case for optimism—they are museums created to actively seek solutions to become more sustainable and in doing so, they promote the well-being of visitors, staff and communities.” (Ironically, the project does translate happiness back into a financial metric, concluding that the individual wellbeing value of museums is over £3,000/year.) Examples of Happy Museum practice include The Beaney House of Art and Knowledge’s “Paper Apothecary” project, in which visitors received a “cultural prescription” from the resident chemist to brighten their day, and the Woodhorn Charitable Trust’s museums, which hosted a comedian in residence.

“The Happy Show” by Stefan Sagmeister, a New York-based designer, is a touring exhibit most recently shown at the Museum of Vancouver (MOV) in Canada. On one of his year-long sabbaticals to recharge from his work, Sagmeister launched a 10-year project to define and control his own happiness, culminating in this installation. MOV notes the exhibit was highly relevant to its community in light of a 2012 survey showing that “Vancouverites were isolated and disconnected.” The museum built out the experience with a series of public events encouraging people to explore various facets of happiness, including a public forum on ideas for creating a happier community.

What This Means for Museums

Nonfinancial metrics are a good fit for the museum sector. In the absence of shared measures of wellbeing, museums often fall back on trying to demonstrate financial impact. Even when such studies are rigorous (and all too often they are not), the argument has an inherent weakness: as soon as a nonprofit grants the premise that its most important contribution is economic, it begs the question of whether a city, state or community could invest the same amount of support in a different entity—for

profit or nonprofit—that would yield a better rate of return.

Given traditionally low museum salaries, it may be realistic for much of our sector to focus on employee happiness and wellbeing, as well as trying to budget financial incentives. And (as Tony Hsieh found at Zappos), this may pay off in mission delivery as well. Museum guru Elaine Gurian contends that “if your staff is happy, your audience will forgive you almost anything.”

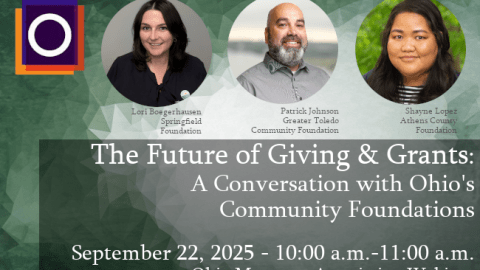

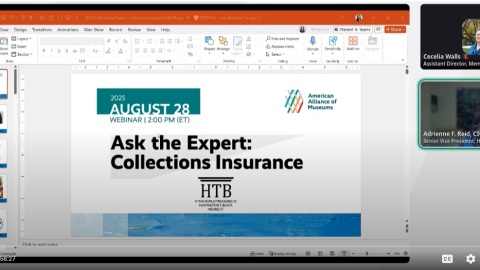

One piece of good news for nonprofits is that charitable giving (along with other forms of spending money on others) seems to increase happiness far more than spending money on oneself. The Arizona-based Lodestar Foundation leverages this aspect of human nature, seeking to “guide us to find happiness through philanthropy.” (This is a

refreshingly transparent approach: “It is all about me, but it helps you anyway.”) Some major foundations embrace wellbeing as an explicit goal. The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, for example, funds research into “positive health,” including the contributions of wellbeing, happiness and marital satisfaction. The Walt Disney Company’s charitable giving priorities include “seeking to bring happiness, hope and laughter to kids and families in need around the world.”

Museums Might Want to…

- Consider what nonfinancial metrics they can use to measure their own success. Museums often emphasize educational outcomes, but that message isn’t penetrating the market very well! According to research by Reach Advisors | Museums R+D, only 12 percent of the general public thinks of museums as educational.

Perhaps happiness would be an easier sell. We have the foundation for building this case: a 2013 report by a researcher from the London School of Economics, commissioned by the Happy Museum Project, demonstrates that visiting a museum is associated with higher levels of happiness. - Establish an internal happiness audit, assess how to create a happy and productive workplace, and validate the happiness and well-being of employees as an explicit measure of success. As noted in the chapter on labor in this report, museums usually can’t compete with the private sector on salary, but they can aim to be the best places to work when it comes to quality of life.

- Make the case that museums are worthy partners in the quest for wellbeing. Charitable foundations may value the ability of museums to improve wellbeing in specific communities. Businesses may want to include museum services in the benefits deployed to cultivate happy and productive employees.

Additional Resources

The quote chosen to enhance this chapter is from a speech Robert F. Kennedy gave at the University of Kansas in 1968. The full text can be found on the website of the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum. The speech has particular resonance for our time as it was delivered when, as he notes in his remarks, violent protests were wracking the country, tanks were patrolling the streets and “machine guns have fired at American children.” Kennedy argues that the US should not rest complacent in its economic prosperity, and delivers a scathing criticism of GDP as a measure of national greatness.

The OECD Better Life Index empowers users to generate their own international rankings by assigning relative importance to 11 topics including community, education, civic engagement, health and life satisfaction.

Daniel Fujiwara, Museums and Happiness: The value of participating in museums and the arts (2013). Commissioned by the Happy Museum Project, this report looks at the impact museums have on happiness and self-reported health. In a concession to the tyranny of economic measures of success, it then uses the Wellbeing Valuation approach to translate these benefits into cash equivalents.

“Fiero! Museums as Happiness Engineers,” Museum magazine, March/April 2009. In this article, adapted from the inaugural CFM lecture, Jane McGonigal makes the case that museums should be in the business of making people happy, and encourages them to be pioneers in the sustainable happiness movement.

William Davies, The Happiness Industry: How the Government and Big Business Sold Us Well-being. For an accessible introduction to the book, download the Future of Work podcast, episode 56, in which futurist Jacob Morgan interviews Davies.