“Anything worth doing is worth doing slowly.”—Mae West

In the past few decades, there’s been a growing awareness that while “fast” may look efficient, in the end it may not be effective. The Slow Movement, composed of distributed, disaggregated individuals and groups advocating similar principles across a range of sectors, represents a cultural shift towards a slower pace of life. It came to world attention in the 1980s when Carlo Petrini founded the Slow Food movement in Italy (now it is international), in large part to fight globalization of food and agriculture and the destruction of local economies and traditions. Now (ironically) the movement is gathering speed, and “slow” is being applied as a business strategy and life philosophy to everything from food to travel to health care, as we rediscover that doing something quickly doesn’t always mean doing it right.

Technology is being widely blamed for shortening our attention span. The median length of a book is 64,000 words; the optimal length for a blog post is 1,600 words (which takes 7 minutes to read); tweets are capped at 140 characters, but do even better if they slim down to a mere 100. The site Long Reads was founded to push back against the ultra-short form of typical Web content. (And if you don’t have that kind of time, you can compromise with the blog platform Medium.) Slow Reading clubs bring people together to provide mutual support of simply curling up in a cozy chair for an hour of sustained attention. We even have Slow TV: in one example, 1.3 million people watched 4 hours of people talking about knitting, then 8-1/2 hours of actual knitting, during Norway Public Television’s “National Knitting Evening.”

Slowing down takes conscious effort because our internal clocks have been reset by over a century of technological advances aimed at doing things faster. In 1873 Jules Verne envisioned Phileas Fogg speeding around the world in 80 days by rail and steamship. Now engineers are working on hypersonic aircraft that could make the trip in 6 hours. The acceleration of travel is eclipsed by the speed of communications, which, on earth, is near instantaneous. (Even sending messages to the Philae lander, as it hurled towards Comet 67P, 673 million kilometers from the sun, took only 28 minutes.) But there is growing awareness that speed comes at a cost. A 2012 study by Pew Research showed that 87 percent of teachers feel technology is creating an “easily distracted generation with short attention spans.” At the same time, we are beginning to

document that “slow” has health benefits—for example, increasing well-being and reducing stress in children.

This realization is leading to changes in a whole slew of sectors as people strive to apply a slow approach to improve quality of life and capitalize on new business opportunities. Slow Medicine seeks to redress what’s been lost in a health care system that gives a doctor 15 minutes to see a patient and no financial incentive to talk things out. Slow Travel encourages people to connect with their surroundings and local culture, sometimes through literally traveling slowly (e.g., via a canal barge), or engaging in inherently slow activities like cooking or truffle hunting. At the extreme of slow travel is Luis Simoes, who is taking five years to travel the world, documenting the trip by sketching. Two years into the journey, he has visited 29 countries and filled around twenty 60-page sketchbooks. Says Simoes, “With this slow travel I feel I can connect with people, cities much more intimately.”

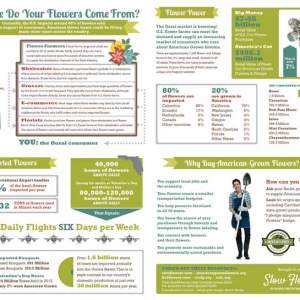

A lot of “slow” is also about creating healthy, sustainable systems. In 2013, the Vermont Sail Freight Project kicked off, aiming to reopen a historic trade route between Vermont and New York State to deliver local food without using oil, reducing the carbon footprint of transportation. Slow Flowers was founded to reduce “flower miles” by connecting buyers with local sources. The gloss is even off fast food, as sales of McDonalds fell 3.3 percent in the last quarter of 2014. Parents are being pressured to make time to make sure kids sit down to family meals, which have been shown to reduce truancy, obesity and drug use, and improve academic performance. The Cittaslow (slow cities) movement, which, like Slow Food, started in Italy and now has three accredited cities in the U.S., is dedicated to improving the quality of life in towns by slowing own the overall pace.

There is a long tradition of Slow Art, but it is being revised and refreshed in imaginative ways. In a world where many buyers choose instantaneous one-click delivery to their Kindle reader, Scottish artist Katie Paterson has unveiled the Future Library project: commissioning 100 stories, one per year, that will only be printed

and read when a forest Paterson’s team planted in 2014 matures and is harvested, pulped and turned into paper a century from now. Or Slow Art may co-opt technology, as in Rob and Nick Carter’s Transforming Still Life Painting (2012), an animated interpretation of Ambrosius Bosschaert’s Vase with Flowers in a Window (1618), which consists of a looping, 3-hour animation that simulates the passage of time.

What This Means for Society

Sometimes we forget that technology doesn’t dictate the future—it simply presents us with choices. Society has to decide how and when to apply any technological innovation, and when consciously push back against undesirable side effects. We may need to develop Slow Design Principles to help us create places and products that foster deeper engagement with places, experiences and each other.

Many of the benefits of “fast” are easy to quantify, particularly the economic gains, while many of the costs are “externalities”—adverse effects that go more or less unseen, and are not factored into the price of cheap, fast goods and services. Fast food leaves society shouldering the costs of obesity and its attendant health effects. Fast (i.e., mainstream) fashion degrades the ecology by diverting limited water supplies to crops unsuited to their climates, fosters abusive labor practices, and contributes to the waste stream by producing goods and fads that don’t last. We need to create systems of pricing or at least of scoring goods that make these costs explicit. Then “slow” may be able to compete on overall cost as well.

Fostering a slower, more thoughtful pace of life may mean re-engineering our cities. Walkable cities consistently score higher on quality of life than cities designed solely around cars. Cities may deploy design principles like shared space to slow traffic and encourage people to linger at shops, restaurants and museums. The principles of New Urbanism emphasize quality of life over “efficiency,” and in that spirit, may encourage city planners to use public art as one way of tempering the pace of urban life.

What This Means for Museums

As with the growing desire to periodically disconnect from the digital world (which we discussed in TrendsWatch 2013), the slow culture movement presents the opportunity for museums to position themselves as refuges from an often overwhelming world. But:

Our field needs to grapple with what it takes to create slow experiences. Sometimes museums wrongly assume that “slow” is simply part of their DNA. A notorious study of visitors in the Metropolitan Museum of Art published in 2001 reported that the average time spent viewing a work of art was 27.2 seconds. A more recent study at the Indianapolis Museum of Art found median viewing times of 4–31 seconds at different installations. It takes conscious and thoughtful work to create slow engagement, with or without technological mediation.

Different audiences will want to engage with the museum at different speeds. Online, museums can accommodate both browsers and contemplators without causing traffic jams. One guy may spend 100 hours, over the course of three years, looking at the digital image of a Modrian, while someone else flips through the virtual gallery. But the rare visitor who tries to spend 30 minutes with the Mona Lisa comes off as looking “eccentric, verging on the insane” as the crowds rush by. As the world bifurcates into fast and slow lanes, museums will have to find temporal or spatial ways to accommodate different paces.

Museum Examples

The Jane Addams Hull-House (JAHH) Slow Museums Project re-envisions the museum as “a site of recreation, reflection and respite.” An Innovation Lab for Museums grant from the Met Life Foundation enabled Hull-House staff to consider a variety of approaches, culminating in the Porch Project, which involved radical teach-ins on Chicago’s grass gap, a yoga and art-making infused workshop on reimagining community safety and policing, a slow food cookout featuring subversive female cooks from Belize and Nicaragua, and storytelling and art installation about community sex education with the Illinois Caucus for Adolescent Health. JAHH’s approach to slowness went

beyond intentionality and sustainability to incorporate notions of resistance based on their internal Slowness Principles.

Slow can also mean ethical and sustainable. In 2013, the Paris Cultural Center welcomed four sheep-in-residence outside the Paris Archives to provide quiet, ecofriendly lawn care (a project they dubbed an “eco-mowing scheme.”) By replacing lawnmowers, the sheep not only reduced the lawn’s carbon hoofprint, they eliminated the noise pollution of commercial lawnmowers.

Many museums engage in projects promoting and highlighting slow culture. The Cooper-Hewitt hosted Natalie Chanin, one of the founders of the slow fashion movement, for a three-day residency followed by a two-day design workshop for teens. The first Slow Art Day, in 2009, had 16 museums beta-testing the experience. By 2012, this had soared to 101 venues and as this report goes to press, 28 venues are already signed up for 2015.

Museums Might Want to…

Establish a baseline. How much time do visitors spend in the galleries, and what is the average and the range? What spaces, or individual collections objects, support the longest dwelltimes? How are visitors’ reported satisfaction, mood and learning outcomes influenced (or not) by the length of engagement with an object or exhibit?

Develop and test strategies to foster slow experiences. Sometimes these methods may be low- or no-tech, human-mediated interactions. Museums might, for example, steal a page from the Human Library, which gives visitors the opportunity to “borrow” a person for a half hour or so of dialogue and interaction. It’s one thing to blow past a painting (or abandon a book), but it’s harder to walk away from a human being looking you in the eye. Participate in Slow Art Day—one day each spring (it will be on April 11 in 2015) when people are encouraged to visit local museums and galleries to look at art slowly, select five works to ponder for 10 minutes each and then discuss over lunch. Further Reading

Further Reading

In Praise of Slowness, Carl Honore, Harper Collins, 2009. An overview of the global Slow movements in various sectors.

Slow Food Revolution, Carlo Petrini, Rizzoli, 2006. A history of the Slow Food revolution by the man who built the movement into a global force.

The World Institute of Slowness. A think tank founded in 1999, the institute provides consulting services as well as promoting slow products and brands. Their blog highlights developments in “slow” in a variety of sectors, including research.

The International Institute of Not Doing Much, dedicated to “sophisticated life in the slow lane.” Distributors of the Slow Manifesto and tireless promoters Distributors of the Slow Manifesto and tireless promoters of Slowsophy. Extremely strange, hopefully tongue in cheek, but fun.

Comments