“When the Internet first emerged, no one could have conceived of the multiplicity of ways it would change our lives; solve function problems, yes, but also radically change our worldview. Wearables have this kind of potential because our bodies are our most intimate pieces of technology: they are entire ecosystems; they consume and create energy; they store and process data; they sense and communicate with their environments.”—Amanda Parkes

Pundits declared 2014 to be the “Year of the Wearable Technology Boom,” as functions that currently reside in our computer, tablet or phone migrated to our body and our clothing. Wearable tech is about seamless integration, invisibility and blending  technology into everyday life. Tech is a wearable win when it becomes an unremarkable part of what we put on each morning. What that technology does is all over the map. Many wearable devices currently focus on biometric analysis (medical data, quantified self, life-logging), but more broadly, “wearables” can integrate any technology (social media, communications, data analytics) onto and into our bodies. The creativity and attention being lavished on hand-held mobile technology may migrate, with time, into wearable tech. And as it does, technology that used to be something we had to pick up, turn on and remember to take with us will become psychologically integrated into our physical self.

technology into everyday life. Tech is a wearable win when it becomes an unremarkable part of what we put on each morning. What that technology does is all over the map. Many wearable devices currently focus on biometric analysis (medical data, quantified self, life-logging), but more broadly, “wearables” can integrate any technology (social media, communications, data analytics) onto and into our bodies. The creativity and attention being lavished on hand-held mobile technology may migrate, with time, into wearable tech. And as it does, technology that used to be something we had to pick up, turn on and remember to take with us will become psychologically integrated into our physical self.

In 2013, investors poured $458 million into wearable companies; in 2014, the market was valued at $5.26 billion; and by 2018, projections of wearable tech in the market range from 130 to 180 million devices. Whether this investment proves to be a giant flash in the pan or the start of the next big thing depends on whether wearables prove themselves to be superior to their hand-held competitors.

The first great challenge for wearable technologies is justifying their existence by doing something your smartphone can’t, or doing it better. In addition to freeing up your hands, some wearables provide a heads-up display (layering data over a user’s normal field of vision), some push data to or from a wristband, some live on your skin or in prosthetic devices, others weave themselves (literally) into mundane items of clothing. See, for example, the Ralph Lauren designed biomonitoring t-shirts worn by the ball boys at the 2014 U.S. Tennis Open. This kind of integration is facilitated by the development of electronic materials that can be stretched, folded, woven and washed.

Skip over related stories to continue reading articleIn addition to collecting data from your body and surroundings, well-designed wearables can provide a graceful, less obtrusive (read, less rude) way of monitoring your various data streams, including e-mail, without staring at your phone.

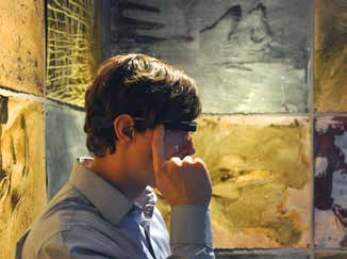

One of the best examples of wearable tech in search of a function is Google Glass, a heads up, hands-off display that enables the wearer to take photos or videos, search or information, track reservations, make calls, send messages, share content and more, using a combination of voice and touch commands. Google is currently paying particular attention to Glass’s potential applications in healthcare, construction and manufacturing, where hands-free information is a valuable work tool. In other circumstances, a less expensive, if less cool, piece of tech such as a head-mounted Go-Pro Camera might accomplish the same thing (for example, taking first-person video of unfolding events). Whether or not Glass per se becomes the next ubiquitous personal tech accessory, there are many competing products in development—wearable tech in general (and doubtless some form of hands-off headset) is part of our future.

Sometimes wearable tech is about making a specific technology less intrusive: such as a wristwatch that lets you sneak peeks at your e-mail, a game controller built into a glove or a small clip-on camera that automatically generates a photostream of your life. Sometimes engineers seem to be vying to see how many functions they can jam into a given piece of apparel: Can a necklace consist of a light display that responds to your movements and ambient noise? If you are going to wear a smartwatch, can you engineer it to predict and display upcoming events? Why can’t your shoes vibrate to tell you where to go? Or create a new form of notation for dance (a notoriously difficult challenge)?

Many of these functions may seem frivolous, but wearable technology is having a profound impact on health care. Wearables can transform medical monitoring into an unobtrusive, portable, personal, always-on function. At the most basic level, the plethora of personal fitness monitoring bands and tags that collect data on movement, sleep and (for some) temperature and pulse, generate data that can be shared with healthcare providers. Epidermal electronic skin patches can monitor biometric data, and paired with diagnostic algorithms may be able to deliver appropriately calibrated drugs (such research is currently being targeted at Parkinson’s and other movement disorders). The Embrace smartwatch can detect the warning signs of an epileptic seizure. Google’s nanoparticle-covered pill pairs with wearable magnets on the skin to detect cancer.

Wearables may transform other fields as well. Consider how wearables could empower citizen journalism, thwart censorship and monitor the actions of police if we can turn people into walking news collection devices. And the data flowing to and from wearables is going to rock advertising, social media and retail: the research firm Gartner predicts that by 2020, consumer data from wearable technology will drive 5 percent of sales from the global 1000 firms.

What This Means for Society

The rise of wearable technology may finally drive diversity in the notoriously white, male tech sector. While most wearables are marketed as “unisex,” what that usually means in practice is “designed for men.” But the tech industry is discovering that “one size does not fit all”—a device that is part of a person’s wardrobe has to take into account gender, size, body type and skin color. And a diverse group of designers is more likely to meet the needs of diverse users. Isabelle Olsson, whom Google drafted to serve as the lead designer of Glass, makes a point of noting that the Glass design team splits about 50/50 male/female, as opposed to the 70 percent male Google workforce overall. Some commentators note that many of the functions of wearable tech, particularly fitness tracking, can be consolidated into that Swiss Army knife of technology, the smartphone. That being so, the dedicated, long-term users of separate monitors designed to live on the wrist or on a necklace may be women, who are less likely to carry their smartphone in a pocket. That, in turn, drives gender diversity by bringing together the worlds of tech and fashion to produce wearables that appeal to a mainstream audience.

Wearables may reshape the workplace as employers use them to measure and tweak performance (including athletic performance on sports teams) or track productivity and improve performance. Some companies, including BP and eBay, encourage employees to wear fitness monitoring devices, and sometimes offer discounts on health insurance in return. Other employers may ban wearables, or at least create stringent policies governing their use because the devices may pose a security risk or inadvertently create records that are subject to retention rules or vulnerable to subpoena.

Wearables may reshape the workplace as employers use them to measure and tweak performance (including athletic performance on sports teams) or track productivity and improve performance. Some companies, including BP and eBay, encourage employees to wear fitness monitoring devices, and sometimes offer discounts on health insurance in return. Other employers may ban wearables, or at least create stringent policies governing their use because the devices may pose a security risk or inadvertently create records that are subject to retention rules or vulnerable to subpoena.

Wearable tech may prove to be a boon for accessibility. Devices like Glass can integrate visual recognition, location-aware information and wayfinding into everyday life. And wearable tech can destigmatize assistive devices, as well as enhance their functionality, by making them either cool or inconspicuous. There is a growing list of must-try wearable tech for people with disabilities, including a variety of heads-up devices that turn visually recognized text to audio. One teenager with severely compromised vision recently discovered that Google Glass expands his visual field by 70 percent, enabling him to resume his ballet practice. Wearable tech also encompasses increasingly sophisticated prostheses that offer enhanced functionality, or fashion-forward design. Imagine, for example, a prosthetic arm and hand for a chef that is touch and temperature sensitive, measures the pH of foods and holds onto slippery foods with suction cups. (OK, that one is just a concept, but engineers are working on it.) In any case, the potential for wearables to enhance accessibility challenges designers to make such devices barrier-free.

As with any new technology, society is playing catch-up when it comes to drawing appropriate boundaries around the use of wearables. In 2014, 59 percent of respondents to a PricewaterhouseCoopers survey had concerns about integrating wearable tech into everyday life that ranged from security breaches to “making everyone look ridiculous.” This may simply reflect the caution provoked by any new technology, but some industries have specific concerns: last year the Motion Picture Association of America and the National Association of Theatre Owners made it clear that patrons refusing to put away wearable recording devices may be booted from the premises. Google is already playing defense against measures proposed in three states to impose restrictions on driving with headsets like Glass. And data from the personal monitors people choose to wear may feed into the growing reach of digital surveillance: last year lawyers in Canada working on a personal injury suit used data from their client’s Fitbit to help make her case. What happens when prosecutors start to tap this source of evidence?

What This Means for Museums

Wearable technology is a logical extension of BYOD (Bring Your Own Device). Museums are already taking advantage of the fact that many, if not most, visitors enter the building with a hand-held device (notably smartphones or tablets) that can deliver interpretive content. As Glass or its kin take hold, museums should ensure that their content works on these emerging platforms as well. Some wearables may open up the potential for types of interpretation not offered by hand-held tech.

Practitioners such as independent consultant Mar Dixon and Neal Stimler at the Metropolitan Museum of Art are exploring how wearable tech can help museums with their own work. Can heads-up, hands-off recording devices like Glass help conservators and preparators, as well as artists such as Gretchen Andrus Andrew, document their work? Could GPS-connected biomonitors help ensure the safety of researchers working in remote and dangerous sites? (Shades of Star Trek away teams.…) Can museums recruit the major players in the fitness tracking industry (Fitbit, Jawbone, etc.) to help measure the biometrics of cultural engagement?

Wearables strengthen the case for museums providing open, remixable content for private and commercial use. This will encourage the development of applications for wearable tech by entrepreneurs working outside museums (many of which lack the expertise, resources and staff to do such work in-house).

Wearable tech creates yet another challenge for conservation. In 2013, David Datuna created the first public artwork designed to be viewed with Google Glass: Portrait of America, which debuted at Art Basel in Miami. As Glass’s software evolves (or eventually is retired), Datuna’s work will pose yet another technological challenge to museums collecting digital artifacts. How can we ensure that a work like this is viewable in 10, 20, 100 years?

Museum Examples

Several museums are experimenting with Google Glass, including the Bard Graduate Center Gallery and the de Young Museum—Glass can use visual recognition to trigger content appropriate to whatever painting a viewer is looking at. The Manchester Metropolitan University (MMU) experimented with using the device to deliver interpretive content at the Manchester Art Gallery, and hopes in the future to provide Glassware that will recommend, and guide the user to, similar works.

The Tech Museum of Innovation in San Jose, California, opened an exhibit in 2014, “Body Metrics,” that explores the applications of wearable tech to health and well-being. Visitors are equipped with three wearable devices, enabling them to collect and manipulate their own biometric data while participating in activities throughout the museum.

Last year the Powerhouse Museum hosted Sydney Design 2014, which included a workshop exploring the research applications of wearable technology. The participants—user experience designers, developers, educators, museum and gallery curators, and fashion designers—created conceptual designs for wearable tech that would help gather data on four hypothetical users: a foreign correspondent in Iran, a sex worker in Sydney, an Olympic diver and a person with Parkinson’s disease.

Museums Might Want to…

Develop proactive policies regarding use of wearable tech by visitors and by staff. Are there areas of the museum, or events (such as staff meetings or public lectures), where wearables may be banned, due to concerns about covert recording?

Monitor the wearable technologies used by visitors, and be prepared to integrate them into BYOD delivery of content and experiences. Support the use of wearables (as well as hand-held devices) by providing free Wi-Fi and charging stations. Explore (with permission, of course!) how data from personal biomonitoring devices might be integrated with indoor GPS to track how visitors experience the museum physiologically and psychologically.

If the museum has created content or experiences that can only be accessed via wearable technology, consider having devices available for loan to visitors who don’t bring their own. This would help bridge the “digital divide” and ensure that all visitors have access to what the museum offers.

Seek out artists and technologists experimenting with wearable tech. Their work may help museum visitors learn about emerging technology and consider the implications or their own lives. They may also help museums explore how wearable tech can be put to work in service of the museum’s goals.

Further Reading

The Creators Project, Make it Wearable|The Concepts is an Intel video series on wearable technologies. The series includes installments on sleep hacking (inducing lucid dreaming through wearable tech), jackets that turn dance into music and biotech nail treatments. Re-collection: Art, New Media, and Social Memory , Richard Rinehart and Jon Ippolito. While not about wearable technology per se, this book looks at the challenge presented by emerging technologies to how we document and preserve art based on new media. http://re-collection.net/ Neal Stimler blogs for the Metropolitan Museum of Art on his experiences using Glass in museums, and you can find his posts at Digital Underground tagged

Re-collection: Art, New Media, and Social Memory, Richard Rinehart and Jon Ippolito. While not about wearable technology per se, this book looks at the challenge presented by emerging technologies to how we document and preserve art based on new media. http://re-collection.net/

Neal Stimler blogs for the Metropolitan Museum of Art on his experiences using Glass in museums, and you can find his posts at Digital Underground tagged googleglass and metthroughglass.