Hi all, Nicole here. Today, I want to share some of my thoughts about museums and the future of museum work that have evolved in the wake of last month’s inaugural Future of Education Road Trip. Over the course of the trip, I had a chance to talk with many thoughtful and committed museum professionals about their visions for the future of museum work. My colleague Sage Morgan-Hubbard and I asked pointedly about how our colleagues in the field were thinking about their own work lives. We initiated conversations with the following questions:

|

| Community Curation at Atlanta History Center |

- What trends do you see in the nature of work (or in the museum workforce)?

- What do you want people to know about your vision for the future of work? What does the future of labor look like to you?

- What do you wish the rest of the country knew about work in your city, state, or region?

Not every person I talked to answered every question. More often than not, discussions of the first question opened up into broader dialogue on the challenges of the profession. Although I’m still processing the insights of people we spoke with, some key themes stand out. Firstly, across the Southeast, museumers I spoke with called for more storytellers and less content masters as they envisioned the future of work in their field. Secondly, museums we visited across the Southeast were forging new partnerships with people who have expertise outside of the museum field. By collaborating with food co-ops, local educators, and parents and guardians among others, museums in the states we visited were expanding the definition of “museum worker” in practice and re-thinking what it means to do museum work. Lastly, many of the folks I talked with were leveraging community power to implement new and non-traditional approaches to work in their institutions. Over and over again, and across various cities and states, museum professionals emphasized that museum work cannot simply prioritize collections, but must consider their collections in concert with feedback from thought leaders, cultural influencers, and members of their local communities.

A Note on Education and Labor

As we planned the trip, Sage Morgan-Hubbard and I decided early on that we would consider the future of education alongside issues of museum labor. The latter has been a focus of much of my work as an ACLS fellow and museum futurist here at CFM. But, I must admit, it wasn’t immediately apparent to me just how closely these issues were connected. Starting out, Sage and I understood that education and labor were linked. I knew, for instance, that the pipeline for training museum professionals is one critical place where inequality can become sedimented. If museum studies programs in this country are 80% white and 80% female, then it can hardly be said that our channels for professionalization are as inclusive as they might be. And this statistic says nothing of the ways that class also shapes our profession. The high costs of graduate education in this country combined with depressed wages in our field mean that young people interested in museum work are increasingly forced to find additional forms of income support, either by working multiple jobs or by relying on family contributions. A recent editorial in the online platform Artsy tackles this question of class head-on by asking, “Can Only Rich Kids Afford to Work in theArt World?” I recommend this article to anyone interested in thinking through the questions of class and access in the field.

|

| Labor and Education at BCRI |

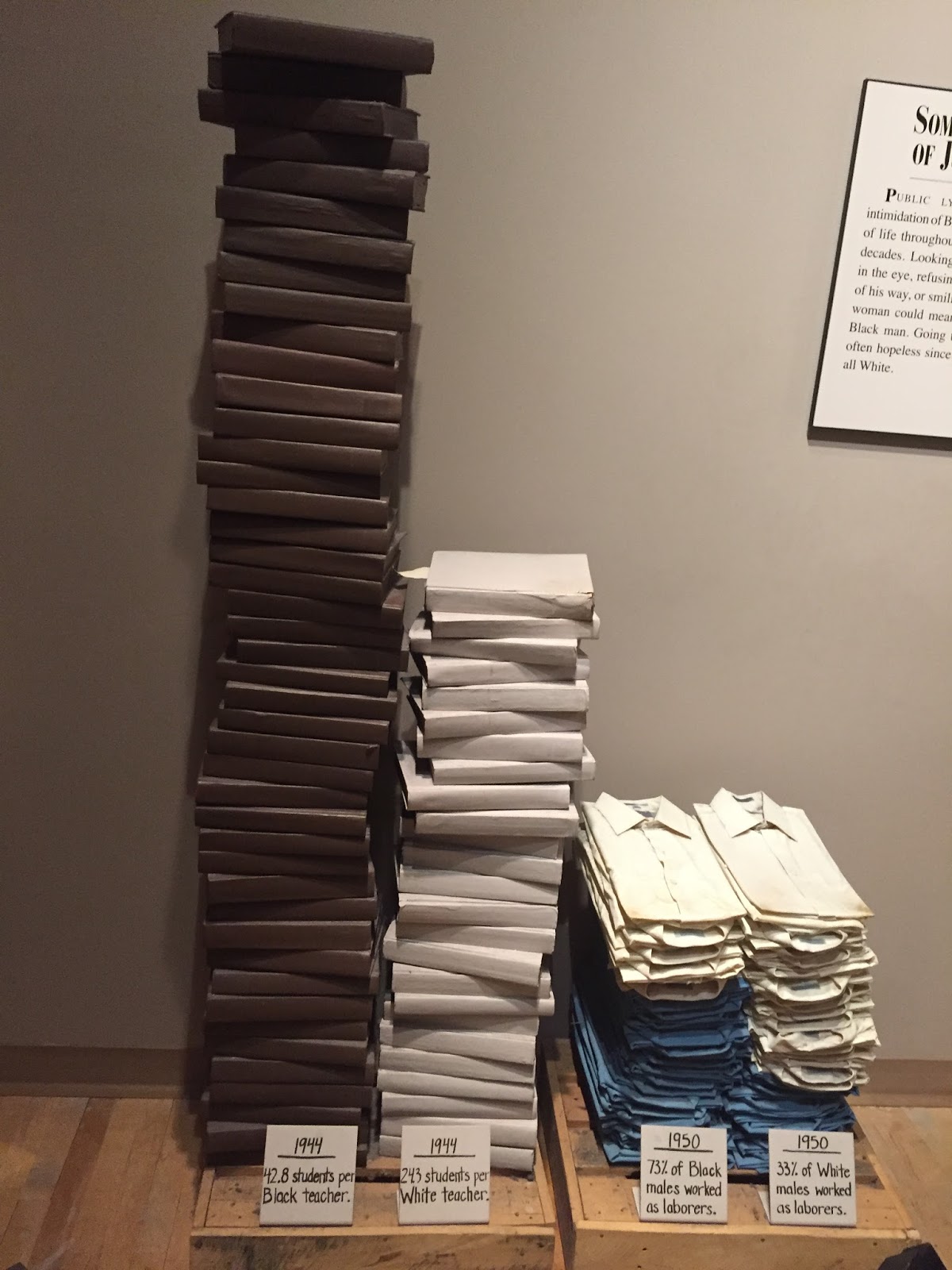

The link between labor and education in museums, however, was dramatized for us in an exhibition at the Birmingham Civil Rights Institute (BCRI). Next to an installation demonstrating the differences between classrooms for white and black students in segregated Birmingham was a plaster rendering of stacks of books and shirts side-by-side. The stacks of books to the left represented the fact that in 1944, the student-teacher ratio in African American classrooms in the region was 42.8:1, and 24.1:1 in white schools. Next to it, a collection of sculpted shirts provided the visual and physical representation for the fact that in 1950, 73% of black males in the region worked as laborers compared to 33% of their white counterparts. The curatorial choice to place education in conversation with labor in such a clear, digestible way underlined for Sage and I that our collaboration was on the right track.

One professional we spoke to during our trip summed up their vision for the future of museum work by saying, “we need more storytellers and less content masters.” Many people I met with shared a version of this sentiment. Museums across the Southeast are refusing to turn away interns who hadn’t taken the coursework in art history and museology that many institutions imagine as prerequisite, choosing instead to use museum internships as training grounds for young people to learn about the field.

Partnering with External Experts

|

| Teen Team Alum (l), Virginia Shearer at the High (r) |

Across the trip, I met with museum professionals at institutions of varying sizes who actively sought out the wisdom and expertise of people outside of the museum field proper. Museum professionals like Dr. Calinda Lee, at the Atlanta History Center, included the voices of educators, musicians, and artists as she and her team were building out their core exhibition. At the High Museum of Art, also in Atlanta, teens develop programming alongside the staff. The High’s Teen Team situates youth as experts in public engagement even as the program trains young people in museum practice. At the WhitneyPlantation in Wallace, Louisiana, Director of Operations Ashley Rogers prioritizes hiring staff from the local area. Members of the staff—from front-of-house positions to operations teams—have deep personal connections to the land and to the stories of the plantation.

Leveraging Community Power

I learned that museums can leverage the power of the entire community as they meet their staffing needs. This does not mean only holding focus groups and community meetings. It means hiring persons from outside of the museum to develop programming, even on a project-specific or consulting basis. Leveraging community power also means exposing young people to museum careers—not just in the hopes of that they will become museum people someday, but because the skills they learn through museum work link up to other facets of their professional lives. As I continue to unpack the revelations from this trip, I am haunted by a question posed to us by Jeff Kollath, Executive Director of Stax Museum of American Soul Music. He asked, “What if we thought about museum jobs as empowering? What would that mean?” These questions open up into others for me, questions that I invite you all to reflect on. What happens when we prioritize interpersonal skills and broader professional experience in our museum hiring practices? What might happen if we make training more accessible for museum professionals? How might we imagine museum work as empowering to both our staffs and our communities?

Hi Nicole, What a great article! You're really taking us on the journey…. heeding the advice of "more storytellers, less content masters!" I wanted to chime in on the question you posed about training. I find that many museum professionals are craving the opportunity to learn from their peers, who they respect and work with. Silo-ing of responsibilities seems to be common challenge for museum staff and particularly difficult for my generation, millennials. In my mind, we are uneasy about the museum careers modeled for us, as we've seen the instability that comes with having a one-track career in the past decades. Though we are passionate about museums in society, society isn't always there to support museums. Opportunities are scarce, funding is tight and the outcome from museum staff can be to squeeze blood from a stone, instead of "watering" (read nurturing) their workforce. Learning from peers, encouraging professional development, even taking management and process cues from other fields, is just one way that museums can be as responsive to their staff as they are to their visitors. A willingness to test and learn with empathy could make a big difference with zero dollars spent and high returns.

Hi Isabella! Thank you for reading with me! I like to say that I'm among the oldest millenials. I get what you mean about the problem of silos. I think many sectors are working to dismantle the kinds of workplace silos that museums wrestle with – some, of course, with more success than others. I love your suggestion of peer-to-peer- and cross-training in museums. And I agree with you that a "willingness to test and learn with empathy could make a big difference" without a huge investment of capital. I think your assessment is spot on. I'm going to think more with your important point about the limits and instability of a one-track career. It seems to me that museum professionals tend to work across functional areas pretty regularly–especially in museums with smaller staffs. I wonder if museums could be more intentional about this multiple and multi-valent work of professionals by build that breadth of functionality into job descriptions, work schedules, and compensation packages. Thanks for such a thoughtful response!!