You can read part one of this series here.

Lately, I’m taking inspiration from a researcher in the ‘60’s: Everett Rogers, and his book “Diffusion of Innovations.” (Hat tip to Richard Evans of EmcArtsfor bringing Rogers to my attention.)

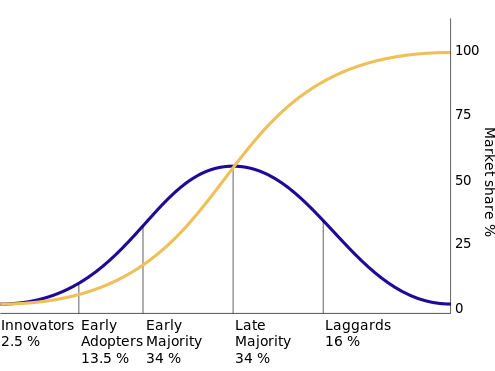

This is the diagram that hooked me:

|

| Roger’s diagram of the diffusion of innovations. As successive groups of consumers adopting a new technology (blue), its market share (yellow) eventually reaches saturation. Shamelessly borrowed from Wikipedia. |

According to Rogers, only 2.5% of a given population are actually innovators. Over five times as many (13.5%) are early adopters, leaping on an innovation once they see what it can do. Another 34% are the “early majority,”—an innovation transitions to a mainstream product or practice as it reaches this group. The late majority (another 34%) will pick up on the trend eventually, and the last 16% Rogers tags as “laggards.” (I find myself calling them ‘dinosaurs,” –that’s my natural history background kicking in again.) Diffusion is the process by which an innovation (whether a piece of technology, a social convention or a system of thinking) moves through these successive cadres of adopters until it has saturated the population.

Rogers postulates that four main elements influence the spread of a new idea: the innovation itself, communication channels, time, and a social system.

The Alliance’s efforts to date around innovation have centered on the first element by helping fund and manage a museum version of EmcArt’s Innovation Lab for the Performing Arts, in order to nurture budding innovations through intensive mentoring and facilitation. When we announced the grants, I braced for a flood of applications, but as it turned out we only received about 30-35 applications per round. Rogers’ framework put that number into context for me. If our PR about the program primarily reached museums that are members of the Alliance, 2.5% of 3000 members would equal 90 museums—close to the total number of applications we received. (Or maybe I’m just rationalizing.)

So, when it came to museums, who are the 2.5% who are innovators? Based on reading the Innovation Lab applications, as well as my observations of museums in the Accreditation and Museum Assessment Program, I see innovation originating primarily from three places in the museum world:

Small museums. I suspect this is because usually:

- They don’t have rigid policies and procedures.

- The staff interact with each other intensively and fluidly across “departments” (to the extent that truly small museums have departments.)

- They aren’t taking a big risk by innovating—they can try things with relatively small amounts of money or staff time that could have a big impact, if they work out, without being a serious embarrassment if they fail.

Big Museums, when they are SO big they spin off little pockets and backwaters where staff can be innovative without rising so high on the radar they get shut down. Sometimes one or two really visionary people, in a small office with bits and pieces of equipment and a license to experiment, can come up with really cool stuff. The problem tends to come when an innovative project takes off and comes to the attention of higher-ups, at which point bureaucracy can kick in and slow down development and adoption of the prototype.

Medium-sized museums that realize that they are in deep trouble, and HAVE to innovate or else they are going to fail. This may be because of immediate financial pressures, or the stark math of changing demographics in their communities. Innovators in this category are drawn from the ranks of museums that suffered the steepest declines in admissions since 2008: those that are too small to compete for regional or national tourists in the age of the “staycation,” but have not built a hyper-local niche for themselves as beloved community hang-outs. Under a visionary leader, museums like this can have the organization and capacity to tackle innovation as an institutional goal, while being small enough to have a shot at changing entrenched assumptions and institutional culture that gets in the way of radical change.

See how this accords with your observations of the museum world of innovation. Which museums do you regard as highly innovative, and what factors helped them to innovate?

Next up in this series: what is the most effective way to accelerate the diffusion of innovation?

Very interesting comments. I am at small University based museum, the C.H. Nash Museum at Chucalissa, located some 15 miles from the University of Memphis campus in an underserved community where we have carried out a consistent five-year program of co-creative and hosting types of events/exhibits with that community. We consider our Museum to be a virtual research/training laboratory for students in our Museum Studies Graduate Certificate Program, interns, graduate assistants and for class projects.

We are fortunate in this regard because our role in applied education for University students also lives into the University's mission of community engagement. We have access to students and colleagues from a diversity of disciplines who can partner in creative and innovative projects. I cannot imagine this opportunity at any other museum in Memphis.

In our case, small is good.