/* Style Definitions */ table.MsoNormalTable {mso-style-name:”Table Normal”; mso-tstyle-rowband-size:0; mso-tstyle-colband-size:0; mso-style-noshow:yes; mso-style-priority:99; mso-style-parent:””; mso-padding-alt:0in 5.4pt 0in 5.4pt; mso-para-margin:0in; mso-para-margin-bottom:.0001pt; mso-pagination:widow-orphan; font-size:12.0pt; font-family:”Trebuchet MS”;}

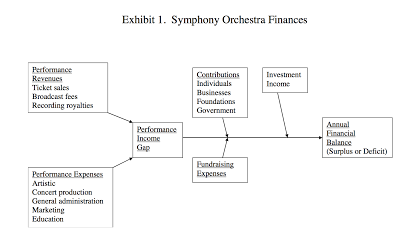

One of the challenges orchestras share with museums is (big surprise) finding sufficient funding to support the high-quality product we want to present. I think the brutal economics of an orchestral performance crank this tension up even higher than it is in museums. There are corners one can cut (up to a point) to fit an exhibition into existing budget. The costs of putting on an orchestral performance (especially given the strong union representation of most orchestral musicians) are largely set and very high. Take a look at this diagram from the Stanford research paper, “The Economic Environment of American Symphony Orchestras,” that I linked to above.

The “performance income gap” between what you can charge for a concert and what it costs to stage is largely bridged by contributions. Let’s assume for a moment that we can’t come up with a radically different economic model. Who is raising the money that builds the bridge?

One set of trends I’ve been following concern professional development. Here is a good study a on the subject from CompassPoint, nicely summarized in the Nonprofit Quarterly, but in brief:

- There are not enough qualified development directors to fill the available positions

- Organizations are suffering from high turnover and long vacancies in development positions

- Executives report performance problems and lack of basic skills among fundraising staff

The report concludes that development has to become a shared responsibility across the organization—an embedded part of many people’s work, not segregated into one specialized compartment. This is in accord with the general push for staff to develop “T-shaped” skills: deep in one area, but broad across a range of competencies. Nowadays, it isn’t enough for a curator to be an expert in her or his subject matter. A curator also has to be good at communicating to a variety of audiences, valuing the input of non-experts, and finding ways for people to participate in the creative process. Many people bitterly resent the fact that they can’t just focus on the skill at which they want to excel—I’m told this is a major tension in orchestras, as well. Many musicians who practiced long hours from a very young age and finally made it into a first rate ensemble, want to spend their time on making the best possible music. Understandable, but increasingly unrealistic.

To launch the Center, the arms of my “T” had to stretch to encompass editing, using social media, presentation, business planning and new product development. Now I, as a program staff member, feel like we (the subject specialists) have to learn to take point on raising funds to underwrite our work, as well. I can’t afford to land back at square one every time staff in the development department turns over—again. The time I spend teaching new staff about what I do, and how to speak about it to others, might be better spent delivering the message myself. Do I still want development staff supporting my efforts? Heck yes! But I think I had better not rely on them too much—in the end, no one can do a better job of convincing people of the importance of what I do than me.

Congress Passes Arts Patronage Charitable Deduction Act,providing full tax deductibility for private support of individual visual and performing artists.

On the heels of this news came a second announcement: a call for auditions for the New South Orchestra, a musician-founded organization dedicated to musical excellence. “A classical musician today has limited opportunities to focus purely on their art ” said New South spokesperson, cellist Mia Lamm. “The majority of orchestras are premised on community service–even in the big six, musicians spend a significance portion of their time on social engagement, education and community service. The New South Orchestra is currently concluding a successful capital campaign to create a state of the art performance space and a modest endowment. For operating funds, our new orchestra has created a funding model that will allow us to focus on artistic excellence by expecting those most invested in that excellence—the musicians themselves, to fund the organization. Each musician, selected through a rigorous, global audition process, will be expected to bring with them to the job their own salary plus overhead. Some musicians will raise this funding through tapping their individual fan bases, built through social media and mobilized through crowdfunding; some (facilitated by the legislation passed today) will find individual patrons; some may fund their participation through personal wealth. This model will enable the New South to offer free admission to our performances, helping to build a broad & diverse audience for symphonic music.

I agree with the challenge, but the proposed solution is so ludicrous as to make me want to cry.

Instead of accepting the premise that society, through its government representatives and other institutions can no longer afford to subsidize essential aspects of our shared cultural heritage and trying to find new ways to self-fund, we need to be making the case against the increasing income gap that concentrates the national wealth in the hands of a few elite – or worse, multinational corporations. To expect the orchestra's second-chair third violinist to have a fan base that can "crowd source" a her own salary or leverage donations (or his/her personal wealth? – Really?) for a share of production costs boggles the mind! Are fine musicians and all other who dedicate their careers to serving the cultural and educational needs of our society not worth being paid, unless they ape the political system that has members of Congress spend more time on fund-raising than on legislating?

Does culture no longer have any intrinsic value unless it can compete in the open market with all the other commercially-driven forms of shallow, instant gratification violent sports and "reality-based" hype of the likes of the Kardassians? They all have masses of professional promoters and marketers that enable them to enjoy six, seven and eight-figure salaries to play games or engage in cynical backstabbing intrigue while the uneducated masses gawk at them. Yet we cannot afford development departments. I don't buy it!

Don't cave in to the so-called "new reality." If you must engage in personal promotion, as we all do, use it also as an opportunity to point out the destructive path we are on, to those of wealth, power and influence who can help return us – to paraphrase an apparently now discredited slogan – to be a great nation that deserves great art, and history, and literature, and education!

Carle Kopecky, Executive Director

The Old Stone Fort Museum, Schoharie, NY.

A brief comment to an interesting post and the ensuing comment by Carle Kopecky. If we are to maintain excellence in performance arts, curation, and in general the intellectual and creative capital that lends intrinsic, social value to cultural institutions we must find realistic ways to fund them. In the present political climate in North America, that funding will not come solely from government or other public agencies regardless of whether in principle it should, and even if we can demonstrate our societal and economic value. Detroit just went bankrupt–the state government is not going to underwrite The Detroit Institute of Art in deference to the cities crumbling infrastructure and services. To be sustainable, cultural institutions need to achieve a balanced funding model that includes something akin to equal parts government or other public support, endowment/philanthropy, and earned revenue. All three of these components require active participation with our audiences at a deep level, which in turn requires us to demonstrate relevance. And yes that relevance means that our experts have to actively engage our stakeholders (whether those be visitors, donors, government reps., students etc) and indeed in some ways to be jacks and jills of all trades.

In the case of museums, curators will: participate in development of networks of participatory followers interested in their specific research and general area of expertise; work with programming, exhibition and web/social media to translate their core work to general audiences in an engaging way that drives attendance and deepens affinity to the institution; and work with development staff to help set fundraising priorities, build cases for support and present those cases to potential donors. All this AND they need to build their intellectual excellence and make significant academic contributions which builds the reputation of the institution and make a significant contribution to the advancement of knowledge and culture.

There is a way forward to creating and maintaining great cultural institutions with intellectual stars, while still keeping our heads above financial water. It will not be achieved either by abandoning our core values and becoming store fronts for contracted exhibitions and programs and static collection maintenance, or by sticking our heads in the sand and hoping someone sees our value and underwrite us. So I agree that our curators of the future will need a T shaped skill set (that said some will be better at parts of the letter than others and if your staff is large enough some specializatioin can be accommodated). Do such people exist? Can their work load be managed in such a way that this task list is achievable? Can they engage the public and still build a program of academic excllence? I think that answer is yes and we are embarking on that experimental path now.

Mark Engstrom

Royal Ontario Museum