“No matter what business you are in, most of the smart people work for someone else.” –Joy’s Law

I see many people I work with having to make hard choices about what conference(s) to go to this year and which professional memberships to renew. When times are tough, there’s a strong temptation to fall back to the group we most closely identify with—paleontologists prioritizing SVP, natural history collections geeks going to SPNHC, botanic garden types cultivating APGA. These are all good and worthy organizations that run great meetings. But…I want to make the case for spending some time with people from organizations as Not Like Yours as possible.

At a gathering of your peers you can benchmark your performance, bring yourself into alignment with the norms for your field and improve what you already do by learning from best practices. This is a good way to improve your existing business model. Hanging out with people from organizations that serve a different audience, or are designed around different assumptions, fosters break-through ideas that can take your organization to a whole new level. As I’ve written before, I’m a firm believer in the “edge effect”—the biological phenomenon of biodiversity flourishing at the intersection of different habitats.

For example: historic house museums are suffering severe attendance problems. Who could help them with that? Susie Wilkening of Reach Advisors says “I’d love to see a children’s museum reinvent the historic house museum for preschoolers. Preschoolers love the familiar, and they all live somewhere (we hope), so houses are very accessible to them. Ergo, historic houses should be awesome children’s museums. And yet their barriers and guided tours present a steep challenge to young children and their families.”

Jennifer Caleshu, at the Bay Area Discovery Museum, echoes this sentiment, observing “children’s museums know a family audience really, really well. What can we teach art museums about reaching those audiences? How can our play-based philosophy transfer to an art museum or history museum? Some of the ‘family’ projects I’ve seen in other museums are very close-ended – there is only ‘one-way’ to complete the art project for example, and lacking in fostering creativity. I would love to see more cross-discipline collaboration!”

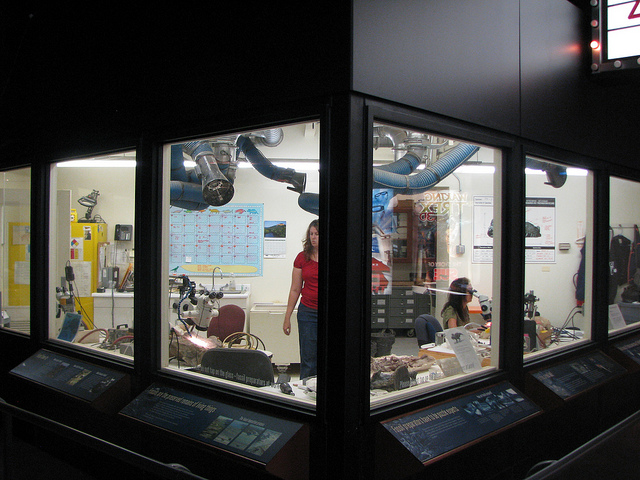

Nik Honeysett, head of administration at the J. Paul Getty Museum, thinks that art museums (in particular) should expose their behind-the-scenes work, and suggests they could learn a lot from their colleagues at natural history museums about how to integrate research and preparation labs into exhibits.

(Photo prep lab at Field Museum of Natural History by Anatotitan, Creative Commons.)

Sometimes the fertile crossover is about content, as much as process. Maria Mortati tells me she was wowed by about a science/art crossover project she was involved in, Phil Ross’ Critter Salon project “Enormous Microscopic Evening” which started as a science event held in a storefront art space, then later produced and held at the Hammer Museum. (You can see a short video of Ross talking about the project here.)

The benefits of mixing it up come not only from cross-disciplinary exchange, but also from working across different scales. Small museums can borrow expertise from large museums that have the resources to invest in research and testing. Ann Fortescue, executive director of the Springfield Museum of Art tells me she wants to maximize the limited educational resources of her smaller museum by applying model educational programming developed by Smithsonian experts to SMOA’s education planning. She is particularly interested in working with the SI Accessibility Office to develop programs for individuals with disabilities. How many smaller museums can afford to create their own accessibility office? Yet small museums have the same legal, ethical and practical obligations of accessibility that a big museum has.

Big museums can learn a lot from small museums, too. As the Small Business Labs writes“One thing we’ve consistently found in our research is that small businesses are natural innovators. Janice Klein, principle of EightSixSix Consulting and former chair of the Small Museum Administrators Committee points out, “small museums tend to be more flexible in their scheduling and can respond more rapidly to new ideas, events or needs.” I’ve spoken with staff at many big museums struggling with how to be nimble and responsive to community interests and current events–how could a large museum program a gallery to operate in a small museum timeframe? Stacy Klinger, co-author of AASLH’s Small Museum Toolkit, observes that because small museums are constantly working with teachers, social workers, newspapers, service clubs and more, they are frequently seen as an integral part of the community. “Successful small museums simply do ‘community engagement,’” Stacy notes, “because there is no other way to do it.”

True, we live in a time of unprecedented virtual content—you can access material from people working in museums of all types and sizes via videos, podcasts, Slideshare etc. (and I encourage you to do so). But some of the most valuable moments of exchange are spontaneous and low key, as when a conversation with the director of Fallingwater (a large historic house in Pennsylvania) led the director of the new (and much smaller) Cade Museum for Creativity and Innovation in Gainesville, Florida to attend the MAAM Building Museum’s conference to learn about architectural competitions. (The Cade’s own competitionis now almost complete, with the winner soon to be announced.) The value of the old fashioned “fly across the country to spend a few days hanging out with folks and schmoozing” conference hinges on this kind of un-programmed face-to-face interaction and serendipitous connection.

So I’m going to disagree with Anita (West Side Story): please don’t “stick to your own kind.” Belong to organizations, like AAM, that bring together people who probably wouldn’t encounter each other any other way. And when you come to the AAM annual meeting, attend sessions outside the usual scope of your work, then go out to dinner with someone from a museum completely unlike yours. Then tell me what you learned…

Comments