Ellen Endslow is the director of collections/curator at the Chester County Historical Society in West Chester, PA.

Last December, a group of thoughtful and concerned museum professionals from across the country participated in Don’t Raid the Cookie Jar: two days of intense discussion about ways museums might create early interventions to avoid the crisis of deaccessioning as a fundraising method (selling permanent collections to pay the bills). The exercise reconfirmed the challenges around this hot-button topic. Upon reflection, the workshop was a microcosm of the very topic we were there to discuss. The experience was thought-provoking and frustrating in a productive way. Readers may agree or not but hopefully will find a nugget in this essay that will encourage ways to move the subject forward.

The Case Study

Dr. Nien-hê Hsieh started the workshop with a compelling for-profit example of a real ethical dilemma. A Harvard Associate Professor of Business Administration focusing on ethics, Hsieh energetically shaped the role-playing. I learned at least two things. One, bold dialogue at the outset of a challenging discussion is a way to put the cards on the table, leading to more meaningful dialogue. Two, ethics aren’t exclusively the realm of museums and non-profits no matter what special place people might think these organizations hold in our society. Although we were role-playing, it was easy to envision non-profit folks being as susceptible as anyone to “selling out” in an effort to stay afloat. The risks in the case study set the stage for the rest of our discussions.

Skip over related stories to continue reading articleRisk Factors

Our next task was to identify possible warning signs of museums at risk. The examples we came up with covered a wide spectrum: rapid staff turnover, deficit budgets, lack of Board participation, capital campaigns masking operating deficits, and no strategic plan. And, there were many more. (You can download a summary of our discussions here.)

I found it interesting that many of us had experienced one or more of the risk factors listed at some point in our careers. While recognizing the potential negative impact of any one of them, risk indicators resembled the challenges of doing business in museums of all sizes. Yet even with these hardships, museums often find a way to carry out their mission. So what is the underlying glue that keeps museums together?

Trust and healthy curiosity may be what enables museums to keep functioning. Of the risk factors discussed, those that threatened both these conditions struck me as potential critical dangers to institutional survival. I’ll touch briefly on a few of these factors below.

Lack of Engagement as Risk Factor

AAM has held numerous worthwhile programs about engaging with our communities because such engagement is a critical prerequisite for museum success on many levels. Engaging with non-community and new community members can help them feel more connected in part because of the museum.

But what about internal engagement with staff (paid or volunteer) and boards? Our workshop discussions surfaced the need for staff in all functional areas to participate in budgeting and finance in order to be able to spot the red flags of financial risks. However, not all museums provide an environment that allows for constructive critical comments that might identify red flag issues. Are there ways museums can give such comments serious consideration? When internal levels of engagement fall, the level of risk to the museum rises.

At all levels, there are “givers” and “takers,” “savers” and “spenders.” This vast array of human nature when moderated well can lead to creative and innovative strategic choices. If any one group in the institutional equation is disengaged or uninformed, however, it is likely to influence choices that result in destructive strategies.

Boards as Risk Factor

It was easy to infer from participants’ remarks that a number of risks revolve around governing boards. I serve on a non-profit board and recognize some of those risks. I am also acutely aware of the concern raised more than ten years ago by a major funding agency. They worried publicly about the lack of qualified museum board members in a region filled with museums. Today that concern doesn’t seem so academic. It is sadly apparent that there is a real risk when governing boards are not interested in learning the basics of the museum standards they are expected to uphold and to which the staff they govern must adhere.

There are, of course, successful boards. Some take the time to learn about a subject that is unfamiliar. But how can we spread such success between museums? Do they have tools that can be shared? Who has the best board orientation? How is diverse board talent harnessed effectively? Maybe we need a platform for stories of successful boards that illustrate the reward of doing more than attend scheduled meetings without getting caught up in daily operations. Without a sense of connection board members have little reason to do anything but drop in, react, and leave.

The workshop itself provided a good analogy for high-functioning board behavior. As we role played the opening case study, we noticed our tendency to make assumptions and look for quick fixes. I wondered if similar behavior might be a key harmful characteristic of disengaged or untrained Boards. Just as we tried to get the job done in an hour, drop-in Board members are likely doing the same thing but without the deep perspective or knowledge of ethics in the field.

From another perspective, workshop participants who attended only the second day shared interesting and impassioned comments but lacked connection to the discussion trajectory. It was an unexpected didactic moment with another parallel to poor governance. Unengaged board members who are catching up are holding everyone else back.

Staff as Risk Factor

Staff can also be a risk factor, sometimes with issues similar to their boards. In addition to needing to be present, and engaged, they are responsible for remaining current in ethical and legal issues and are often in the position of informing others. Remaining current, however, may become a struggle if professional development is unaffordable or even discouraged. And those who are knowledgeable may be at risk themselves if no one else, including their supervisors, has any interest in hearing what they have to say.

An environment of mutual respect allows for candid dialogue. Without it, there is significant risk. Are staff willing to be museum advocates within their own institutions? Are leaders willing to listen to staff, and vice versa? Is each curious about how the other works? Do museum professional training programs create consistent professional standards? Do training programs provide constructive communication techniques? Does each one of us serve in a way that we want to be served?

Inadequate staffing levels is a clear risk. Managing appropriate deaccessioning is one method of avoiding future crises. However, it is difficult to undertake timely deaccessioning if you don’t have enough staff. Temporary staff, though sometimes considered a solution, may have limited vested interest in the mission. They may be effective when filling a temporary need or working in the manner of Dr. Hsieh, who encouraged discussion to help the workshop group use the information at hand to find its best conclusion. But without institutional engagement, clear direction, and broad buy-in, recommendations from temporary staff may miss the mark or fall on deaf ears.

The Challenge of Creating Toolkits

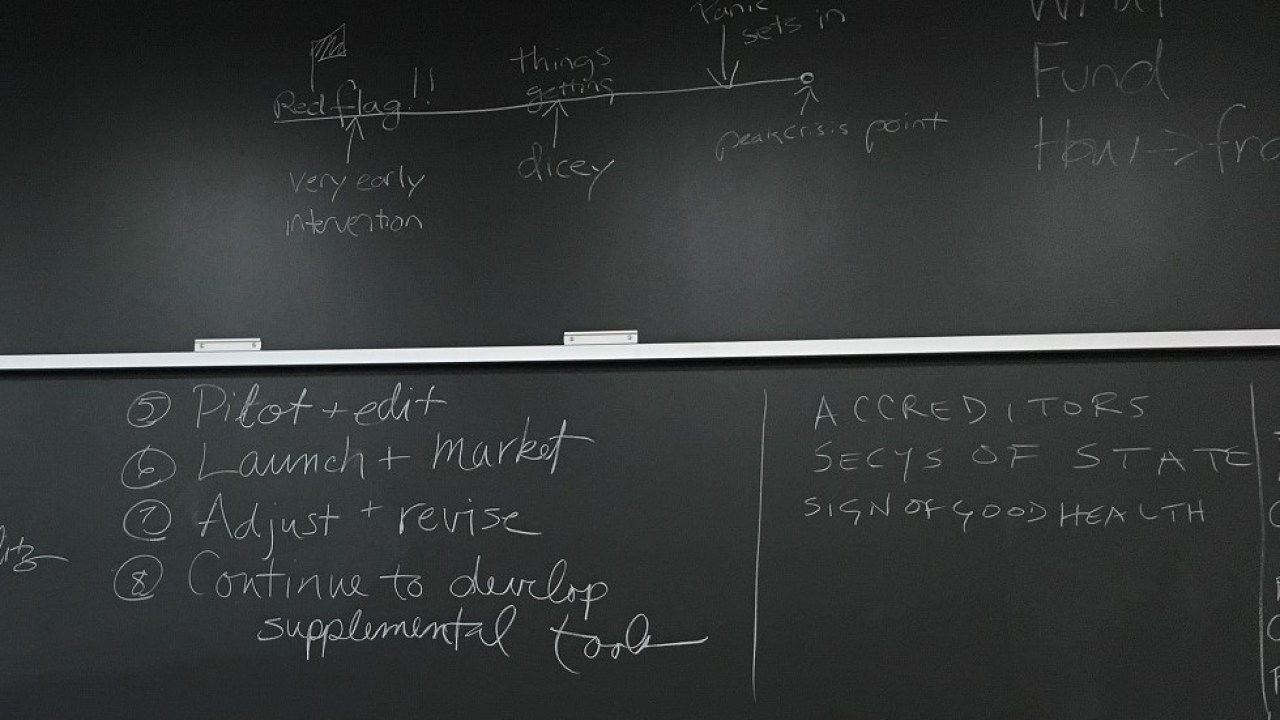

Our last assignment at the convening was to develop and share ideas and tools that might help museums in financial distress before they resorted to selling collections. The nature of these tools would determine when they could be deployed in the timeline in an institution’s journey from red flags to a full-blown crisis. This was a difficult assignment. For one thing, I think it could be hard for a museum to accurately determine whether it is actually on the brink of a crisis, or merely going through a rough patch.

In my board work for a philanthropic organization, we regularly evaluate local chapters to ensure they understand appropriate organizational processes. I wonder if this might be a model that could benefit museums. Accreditation doesn’t fit the bill because it is evaluative rather than consultative. AASLH’s StEPs program and the IMLS funded Museum Assessment Program run by the Alliance might help. But could either of these programs benefit an institution that has hired a new director from outside the museum profession to “make change?” How willing might that person be to use a toolkit from the Alliance or from other organizations?

Hopefully, this workshop is the beginning of useful conversations in museums of all sizes across the U.S.

There is certainly no one-size-fits-all solution. From where I have sat for more than 20 years in the profession in several regions and hearing from dozens of people, this conversation is a unique opportunity to fill an important need. If we have the courage to address discontinuity and learn from success, we have a greater chance of increasing the impact museums have on our constituents and on the people who are making them function without losing our moral compass.

About the Author

Ellen Endslow has over 20 years experience in the museum field. In addition to being the director of collections/curator at the Chester County Historical Society, she is also chair of AAM’s Professional Network Council and the past chair of the Curators Committee Professional Network.

I was sorry to be unable to attend the event as deaccessioning has been a museum subject of mine for many years (and lots of writing). Rowman & Littlefield has just published my book on the subject:

Deaccessioning Today: Theory and Practice.

Any relatives in Peabody MA?