This article originally appeared in the July/August 2016 issue of Museum magazine.

Pursuing a future in which provenance research and data are efficient, accessible, and equitable.

Museums know that provenance, including provenance research, is important. It’s important for proving authenticity, for ethical collecting practices, for interpretation, and for good collections management. And yet, as the museum community increasingly embraces openness and digital tools and workflows, provenance seems to have crystallized. The importance of provenance is not in question, but the costs of doing provenance, both monetary and human, can be paralyzing, demoralizing, and prohibitive.

But maybe it is time to take a fresh look at provenance. Perhaps we should consider it not only as an academic exercise, added to the backs of catalogues for a few connoisseurs who enjoy such things, but as a tool for understanding our collections, the people linked to the objects, and, through those narratives, the interactions of people and objects across time. Ultimately, provenance is the tool that can help us talk to our visitors about the humanity in objects, and that’s the main reason why I think it’s worth the effort.

Defining Provenance

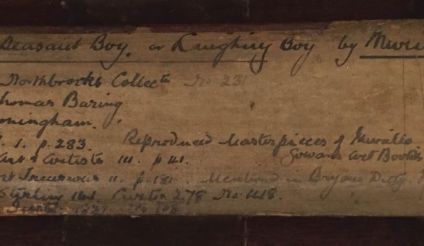

On paper, provenance sounds simple: the ownership history of an object. It went from person A to person B, to person C, to a loving museum. However, provenance is a thorny, slippery thing. I’ve changed a single record ten times, adding a hundred years of history, in an afternoon. I’ve also toiled for months with records that gave me only silence, the documents of the past refusing to make themselves known. I swim in and out of archives, navigating a dizzying array of languages of which I have a tenuous grasp, hoping they will whisper a clue.

I say this as a researcher in a position of immense privilege. I’m part of an urban organization with a decent-sized staff, a collection of a comfortable size (33,000 objects) that happens to have 125 years of archives, and colleagues with more than 20 years of service to the institution. My work has been made possible through extremely generous grants from IMLS, Kress Foundation, and the National Endowment for the Humanities, and, of course, supported by dedicated development staff. Did I also mention the 1.2 million-item library that adjoins the museum and the specialist academic art library across the street?

Doing provenance work in this abundance, while still difficult, is a joy. But what good is it if a researcher must be surrounded by all and sundry to be successful in his or her work? If it is challenging for me, attached to a major museum in Pittsburgh, to get access to data, what must researchers in smaller institutions located farther from the provenance epicenters of New York, Los Angeles, and London be experiencing? And what of institutions lacking the resources to send researchers to distant libraries on unpromising quests?

If we believe that provenance is important, then we must believe in and actively pursue a future in which provenance research and data are efficient, accessible, and equitable. We must work to make provenance part of the fabric of interpretation, presentation, and documentation in museums.

A Worthy Struggle

Let us first acknowledge the truth: Provenance is hard. The work of provenance not only requires knowledge of an expansive arc of human and art history, the ability to switch languages four times a day (or minute), exceptional skill in deciphering handwriting, and the confidence to beg, wheedle, and cajole for archival information and inter-library loans. The successful researcher must embody a trait perhaps best described by the Pittsburghese word nebby: to relentlessly pursue information, shamelessly ask questions, and then efficiently tell the whole world about it.

Finding a candidate who has all of those skills and is willing to work for the salary provided is the definition of a purple squirrel hunt. But many of those same skills exist in the people we already work with, and some smattering of them can be found in the skill set resume of any solid potential hire. So, perhaps we need not hunt the purple squirrels, but rather encourage staff to utilize the skills they already have and to strengthen their areas of weakness. Provenance is a task, one that few people have the capacity to do full-time; but with a critical mass of people able to analyze, record, and write provenance, the process becomes less of a chore.

Developing provenance skills involves embracing ambiguity—something most staff have not had to do in the past. It means accepting that the answer may or may not exist, or that your Rosetta Stone document was burned during World War II, or that a library just will not lend. It means accepting repeated and constant defeat. It means departments must accept that staff may have very little to show for their efforts at the end of a line of inquiry. Sometimes, the only evidence is no evidence. And that’s OK.

I want to frame all of this messiness as a feature, not a technical bug. Some of the best provenance discoveries happen when you’re looking for something else. When we do provenance, we’re adding to our toolkit of information, even if we don’t add years to a record. Further, while collections documentation and research may not be the alluring aspects of museology, working in this area provides a bedrock for interpretation, conservation, and curation.

The Access Issue

Say your colleagues have embraced provenance as part of their practice and are empowered to do this research. Everything should be golden, right? Except there’s this thing called access. Access to objects. Access to information. Access to people. Barriers on any of those fronts can swiftly kill a line of inquiry. It is also a sad fact that there is a positive correlation between access and money. Money pays for reproduction fees, research trips, translation services, and independent researchers. What is a smaller museum or a museum without significant financial resources to do?

While it is an unfortunate truth that money solves problems, the more equitable solution is to eliminate as many of the barriers as possible. The easiest barrier to lower is the one blocking access to data. If two museums have items with a collector in common but one has documented an additional piece of information, the other museum’s provenance provides a bright line of inquiry. If two objects share events A and B, might they also share C?

Many museums already provide collections information on their websites. Some go even further and share raw data on GitHub. But, a paltry number include provenance or exhibition history. The decision to not publish provenance is understandable. With records constantly changing, why publish information to the web if it might soon be wrong? And considering the implications of restitution and legal battles, some might fear (wrongly, in my opinion) a wave of litigation.

When provenance was considered of interest to only a few subject experts, museums’ decisions not to highlight this content were understandable. But that is not the world we inhabit today. By publishing provenance online, we enable ourselves to update the data at any time, and that means that we’re providing our public with our current best understanding of the object.

When Carnegie Museum of Art decided to publish its collections data and to include provenance, we provided very clear disclaimers: The data is subject to change. It is not certified or warrantied by the curatorial staff, and you use it at your own risk. But we also included clear instructions on how people could send us corrections. It opened a line of dialogue between the public and the museum. While we’re still the authorities on our objects, this exchange gives us a chance to absorb new information and to challenge our own understanding.

Creating this dialogue was as easy as telling people whom to contact. Strangely, contact information is one of the hardest things to find, but one of the easiest to provide.

But even more important than proper signposting is letting people know what you have, what they can get, and how they can get it. I advocate for museums having as few restrictions on access and information as possible. While we review our policies on facilities, collections, and security on a regular basis, how often do we review policies on information and object access? And if an access policy exists, can the public find it?

Often, museums veil their offerings in the ominous and vague language of “valid research questions only” and “qualified researchers.” What makes a researcher “qualified”? What, exactly, is a “valid” research question? Lobbing a request into that void may seem like a waste of time and resources when it isn’t even clear who is qualified to ask a question.

I don’t believe that these guidelines were intended to hold back researchers. I’m sure they were formed out of an abundance of caution and protection for the items and information held in the public trust. However, the cumulative effect of opaque access and information policies is discouragement. These access hurdles harm the public trust and perpetuate the idea that museums are for an elite few.

And if we are stewards of collections for the public trust, isn’t the information and metadata of those collections also held in the public trust? Today, our obligation to the public means not only preserving, protecting, and presenting an item, but also granting access to the metadata associated with that object. It seems impractical to spend money on generating data, and then restrict its usage to an infinitesimal subset of the population. By sharing data, or at least lowering the barriers to it, museums can see an exponential return. Plus, this level of transparency is a growing expectation of visitors, as well as museum peers.

New Tools

Even if provenance is challenging, it is an amazing time to be doing this research. The push toward fully digitized publications has advanced provenance by leaps and bounds. The Getty, the Philadelphia Museum of Art, and the Frick Art Reference Library have made an ocean of fully digitized auction catalogues, historical commentary, and other documentation available on sites such as the Internet Archive and HathiTrust. These efforts have made provenance exponentially more efficient. Having publications digitized also means that fewer people are handling delicate materials and rare books but more people have access to the information contained therein. It’s a win for preservation and a win for those seeking access.

Some museum libraries serve their library catalogs to search tools like WorldCat, but while they hold a vast quantity of provenance materials, many will not lend physical copies, even with fee-based interlibrary loan requests. It would be unrealistic to ask all museums to begin lending, as so many lack a dedicated librarian, but maybe this is an area where we can find new and innovative ways of connecting people and information through digital tools.

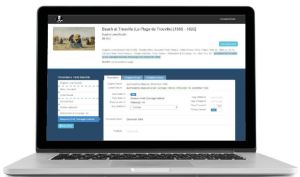

There also are new tools to help in the writing and analysis of provenance. For two years, Carnegie Museum of Art has been working on an IMLS-funded project called Art Tracks, involving cross-departmental collaboration among Lulu Lippincott, curator of fine arts; Costas Karakatsanis, provenance researcher; David Newbury, lead developer; Neil Kulas, web and digital media manager, and me, collections database associate. The goal of Art Tracks is to turn the word jumble of provenance into semi-structured text, with aspirations of doing linked-open-data mapping. Converting provenance to semi-structured text means that the essential components of provenance—like names, life dates, locations, and methods of transfer—are identifiable as being the same. A name is a name. A birth date is a birth date. When pieces of information are identified as being the same, users are able to investigate the data in more complex and nuanced ways. To accomplish this, Art Tracks has generated a new standard for writing provenance that uses AAM’s suggestions but adds specificity in terms of transfer, dates of ownership, and certainty of data.

While forming the standard, we discovered that part of the problem with writing useful provenance is that it is hard for a human to be precise and stringently consistent. So, David Newbury created a tool called Elysa that helps users write text that adheres to the new provenance standard, removing some of the opportunity for human error. Elysa simplifies composing provenance to filling in a series of data fields, which the system then turns into a paragraph. Because the text generated is now semi-structured, it can be used in further analysis on provenance across the collection.

Elysa also uses data ingested from the provenance and exhibition fields of a collections database to generate a timeline. It highlights inconsistencies in data and highlights areas for possible research, like an exhibition that focuses on a period during which the ownership of an object is unclear. If a catalogue can be found for that exhibition, an owner may be listed as a lender, and thus the provenance is improved.

To underscore the importance of sharing knowledge to provenance research, the standard and the software to implement Elysa are open-source and available for free at the Carnegie Museum of Art GitHub page at http://github.com/cmoa.

It needs to be said that all of these things are only tools. They will help, but they will not—and cannot—replace people. Provenance still requires critical, ever-questioning humans to move the data from supposition and assertion to fact and documentation. The work will still be tough. But I assure you: even on the most frustrating day, provenance is worth it.

Tracey Berg-Fulton is a collections database associate at Carnegie Museum of Art in Pittsburgh. She is currently working on the Art Tracks provenance project. She has served as web chair of the AAM Registrars Committee since 2012.

Comments