This article originally appeared in the September/October 2015 issue of Museum magazine.

Progress and looking ahead

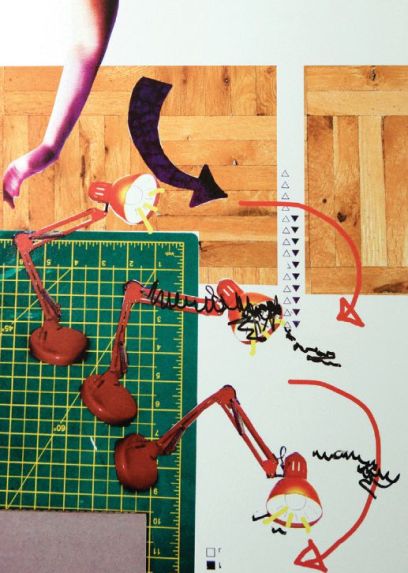

These artworks were on display in “The Art of the Lived Experiment” at the DisArt Festival, which aims to change perceptions of disability.

Our country has been celebrating the 25th anniversary of the passage of the ADA with commemorations, concerts, festivals, parades, social media conversations (see #DisabilityStories, #ADA25) and gala events. Throughout this past summer, people took time to reflect on how far our country has come in ensuring full inclusion for people with disabilities. In the past quarter of a century, there has been an increase in opportunities for employment, education, transportation, healthcare and participation in public life, as well as significant progress in terms of acceptance, attitudes, and perceptions about disability.

Within the cultural sector specifically, there has also been progress for inclusion of people with disabilities. Museums have been steadily incorporating accommodations and programs that ensure inclusion for all visitors and participants. For people with vision disabilities, museums are using audio guides, large-print labels and materials, and content in Braille, as well as tactile tours, models and maps. For people who are deaf or hard of hearing, institutions offer captioned video, sign-language interpreted tours, assistive listening devices, real-time captioning and sign-language interpretation. Museums are also paying more attention to physical access by ensuring wheelchair access to all physical spaces and installing exhibits and displays at heights that accommodate people in wheelchairs or those of short stature. Additionally, museums are more apt to offer seating options throughout galleries and have increased accessible seating in auditoriums.

Museums have also responded to particular conditions and circumstances as evidenced in new partnerships with the autism and Alzheimer’s communities. Specifically, many museums offer visiting times for families with members on the autism spectrum when galleries are less crowded, special materials to help orient new audiences, and educational programs for people with dementia and their caregivers.

Many of these innovations in accessibility are due to the passage of the ADA in 1990, but the advocacy work began much earlier. When the Rehabilitation Act was passed in 1973, federal agencies were required to make their activities, and those that they fund, accessible to individuals that receive their benefits. This meant that museums receiving funds from federal agencies such as the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA), the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH), the Institute of Museum and Library Services (IMLS) and the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) had to begin looking at how they welcomed visitors with disabilities.

Since the 1970s, the NEA has educated its grantees about these requirements, while also working with its network of state arts agencies to help them interpret how best to assist cultural organizations with the accessibility requirements. The NEA published a handbook called Design for Accessibility: A Cultural Administrator’s Handbook, which provided easy-to-use information and resources on making programs and facilities accessible. The most recent version, published in 2003, is still used as a reference guide in museums across the country. The NEA, working in partnership with NEH, IMLS, the Institute for Human Centered Design and other organizations, is updating the guide and will launch a new, comprehensive Web resource in 2016.

The NEA also partnered with the Smithsonian Institution and other museums to educate the museum field and provide resources for museum and exhibit accessibility. The Smithsonian took a leadership role in not only ensuring accessibility in its own programs and exhibits but by guiding science, art, culture and history museums across the country through its various publications and resources, including the Smithsonian’s Guide to Accessible Exhibit Design. The NEA worked with early champions of museum accessibility, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Boston’s Museum of Science and the Museum of Modern Art, to incorporate access and inclusion programs. Additionally, the NEA worked with the Graphic Artists Guild to develop a set of accessibility symbols, used in museums across the country; helped build the field of universal design; and was the first to work with museums to provide audio description of art for visitors with vision disabilities.

Despite such efforts, people with disabilities are still underrepresented in museum visitorship. A recent Survey of Public Participation in the Arts conducted by the NEA finds that adults with disabilities comprise less than 7 percent of all adults attending performing arts events or visiting art museums or galleries, as surveyed in 2012. The data also reveal that 21 percent of all adults visited an art museum or gallery, but only 11 percent of adults with disabilities made such a visit.

According to the Census Bureau, the Baby Boom population is turning 65 at a rate of 10,000 per day, and by 2030, 20 percent of the US population will be over 65, which will potentially increase the number of people with diminished eyesight, hearing, mobility and cognition. In addition, according to the 2013 American Community Survey, there are 3.6 million veterans with service-related disabilities, and more people with disabilities are living independently in communities, increasing the potential audience of museum visitors.

Museums can benefit from attracting and retaining this valuable pool of visitors. Although museums have worked to increase their audiences of people with disabilities, there is still much to be done to involve those with disabilities in the curatorial, content and decision-making activities of museums. Such a gap is noted by performer and activist Mat Fraser in his exhibit and performance piece, “Cabinet of Curiosities: How Disability was Kept in a Box.” Fraser addresses this issue by challenging museums to question their view of people with disabilities as objects of exhibit and display, and to include their voices and experience in the work of the museum. As evidenced by the disability rights movement’s slogans, “nothing about us without us” and “nothing without us,” people with disabilities should be included as curators, exhibit designers, artists, historians, scientists, administrative staff, Web and application developers, and volunteers. They need to be a part of the conversation and the work of museums.

Universal Design

A reality facing society and museums is the large population of older people—the 78 million baby boomers who are living longer than previous generations. These individuals are facing the physical challenges that come with growing old, as well as a range of cognitive issues like Alzhiemer’s and dementia. Valerie Fletcher, executive director of the Institute for Human Centered Design (IHCD), shared in a 2010 AAM webcast that the aging of the world’s population

is the “most dramatic catalyst” for universal design—the design of products and environments to be used by all people, to the greatest extent possible, without the need for adaptation or specialized design. IHCD advances the role of excellence in design in expanding opportunity and enhancing experience for people of all ages and abilities. Universal design affects a museum’s built environment and the ways it communicates with visitors. When a museum embraces the requirements of the ADA, it can also embrace the spirit of the ADA by incorporating universal design principles. As a result, visitors of all ages and abilities can enjoy museum facilities and programs.

“One of the challenges of universal design,” cautions Fletcher, “is to get people to appreciate that we’re really talking about everybody. You have no idea who has heart disease. You can’t guess who has less vision and you can’t guess most people who have hearing loss. The people whom we need to welcome have non-apparent conditions.”—Greg Stevens

Learn more about the Institute for Human Centered Design at humancentereddesign.org.

Leading the way in this regard is the DisArt Festival, launched in Grand Rapids, Michigan, this past spring. The festival’s goals are to change perceptions and ignite conversations about disability and how it informs artistic practice. The festival and its follow-up activities have drawn more than 20,000 visitors, featuring hundreds of artists and community members with disabilities. The festival’s success was due in part to its many community partners, including the Urban Institute for Contemporary Arts and the Grand Rapids Art Museum. The festival’s centerpiece was an exhibit curated by Amanda Cachia and funded by the NEA, called “The Art of the Lived Experiment.” The exhibition, initially presented at DaDa Fest in Liverpool, England, featured more than 19 US and international artists whose sculpture, video, painting, drawing, photography, ceramics and performance creatively examined disability from an experimental point of view and addressed the uncertainty and change in both art and life. Through this exhibit and numerous additional exhibits, films and community events, the DisArt festival succeeded in its mission to change perceptions of disability, effectively involving those with disabilities in all facets of the event.

Museum Access Consortium

One important aspect of the accessibility and inclusion movement is an increased awareness about people with cognitive or developmental disabilities, including those who are near or on the autism spectrum, people who have mental health issues like schizophrenia or bipolar disorder or adults who have Alzheimer’s disease or dementia. Museums have a continuing part to play in their lives and can be useful in bridging communications between families, caregivers and the person with the disability. A well-designed program for people on the autism spectrum and their families, for example, can positively impact the museum experience for the family and whether it becomes something that is a future choice in leisure-time activity. The Museum Access Consortium (MAC) in New York is a dynamic model of a group addressing this particular audience. MAC was formed by a small group of museum and disability professionals that started meeting informally to discuss topics related to accessibility at their New York-based institutions. In the past five years, MAC has hosted 10 professional development workshops, a public fair, a symposium and a new website focused on improving accessibility for visitors who have autism. Overall, MAC offers a network of mutual support to help practitioners engage with disability advocates and people who have disabilities to learn about, implement and strengthen best practices for access and inclusion in cultural facilities of all types throughout the New York metro area and beyond.

“We have learned from our collaborative efforts these past several years that there is a great need to better reach and meet the needs of adults with autism at cultural institutions,” says Cynthia VandenBosch, MAC’s project leader of Cultural Connections for People with Autism. “It’s been exciting to see how bringing people together in a safe and supportive space to openly discuss their experiences and challenges has led to more thoughtful, innovative and inclusive programming across the city.”

“Over the next few years, [MAC will] be leveraging the foundation we’ve been building to focus on specific areas of growth,” she adds. “We’ll be sharing findings, case studies and resources nationally and researching and documenting best practices in engaging adults with autism … to develop life skills with a focus on job readiness and skill-building.”—Greg Stevens

Learn more about MAC at museumaccessconsortium.org.

What else can museums do to ensure full inclusion? The options are unlimited, but to name just a few:

- Consider the legal requirements and design standards set by the ADA as merely the minimum standard and expand efforts to ensure full access and inclusion for everyone.

- Incorporate universal design principles throughout the museum, ensuring that exhibits and facilities are designed to be accessed by all people, to the greatest extent possible, without the need for adaptation or specialized design.

- Consider accessibility from the start when developing and designing exhibits and programs, not as an afterthought.

- Incorporate the best practices listed at the beginning of this article throughout the museum experience.

- Work with curators and exhibit designers to design exhibits that are accessible to not only those with physical disabilities but also those with sensory or brain-based disabilities.

- Pay attention to exhibit and display heights and font sizes to enable viewing and engagement for people of all abilities.

- Establish an advisory board of people with disabilities to advise on access and inclusion.

- Partner with local disability organizations to help inform your museum’s work and develop new audiences.

- Train all staff to be fully aware of accessibility requirements and how to provide accommodations, rather than relying on one person or department.

- Take affirmative steps to recruit staff and volunteers with disabilities.

- Work with local college and university disability offices to recruit interns and graduates with disabilities.

The future offers many opportunities to expand access through technologies such as 3D printing, mobile applications and new adaptive devices, as well as partnerships with the disability community and design with disability in mind from the start. Disability is a natural part of human life and offers a broad window into the human experience, from the perspective of the arts, culture, science, technology and history. It is a perspective that museums should embrace.

Beth Bienvenu is accessibility director, National Endowment for the Arts, Washington, DC.

Comments