This article originally appeared in the September/October 2012 edition of Museum magazine.

Presidential libraries are in fact archives and museums. They display exhibitions, both permanent and temporary, and serve as public forums for discussions and debates. According to NARA’s website, archives.gov, the libraries present presidential records to the public “for study and discussion without regard for political considerations or affiliations. Presidential Libraries and Museums, like their holdings, belong to the American people.”

But the politics don’t stop once a presidency becomes a library. These institutions come with their own set of behind-the-scenes squabbles and public protests. Difficult decisions must be made about how to present the difficult decisions every president has made. And much like the president, presidential libraries rarely please everyone.

The presidential library system is a relatively new one. Many records from the first 30 administrations are housed in the Library of Congress or belong to historical societies or private collections. Many others, though, were shredded, lost, destroyed by improper care or sold to the highest bidder. During his second term in office, President Franklin D. Roosevelt, following the advice of historians and scholars, established a public repository to preserve his own records. He raised private funds to construct a facility and then turned it over to the National Archives; a system that remains in place today.

Congress passed the Presidential Libraries Act in 1955, establishing a system of libraries that are privately funded but publicly maintained. The act encouraged presidents to donate their historical materials to the government, at which point they would be preserved and made available to the American people. This “encouragement” turned to requirement with the Presidential Records Act of 1978. Another update in 1986 mandated that the private foundations associated with the libraries provide endowments to offset a portion of their maintenance costs.

The National Archives-more specifically, the Office of Presidential Libraries-now oversees 13 institutions, representing presidents from Herbert Hoover to George W. Bush. Along with establishing the libraries’ policies and overseeing their budgets, the office is responsible for working with each administration to ensure its materials are preserved for the public. However, it’s up to individual presidents to initiate the construction of a library. “We have found that former presidents and first ladies are very interested in the project,” says Susan K. Donius, director of the Office of Presidential Libraries since February 20!2. The president decides where the library will be located and designates a foundation to plan it. Donius’s office coordinates closely with this foundation, which funds the library’s entire infrastructure.

President Obama has been mum on where he might like his library to be located someday, yet the issue has already become a source of debate. He had only been in office for a few months when the University of Chicago began looking into the benefits of hosting the imagined library, according to the Associated Press, which also reported in 2010 that the University of Hawaii had undertaken preliminary searches for a potential library site.

The University of Chicago has since been more reticent about its aspirations. A statement from the school’s press office in 2012 says only: “The University of Chicago was fortunate to have President Obama on its law school faculty for 12 years and to benefit from Mrs. Obama’s leadership in several senior administrative roles. It is premature to discuss a presidential library.”

But Hawaii is pushing forward. Leading the effort is Robert Perkinson, professor of American studies, who is working with university officials, state officeholders, philanthropists, and nonprofit and business leaders to find a site, develop a museum and policy plan, and write a proposal to present to the president when the time comes. Beyond being Obama’s home state, Perkinson says, Hawaii is a more “interesting choice” than Chicago for the presidential library. “Obama has a cosmopolitan background and is a global president. A presidential center in Hawaii would have an outward orientation,” he stated in an e-mail. “There are a number of heartland presidential libraries. None of them are really global institutions.”

Of course, hosting the presidential library would also benefit Hawaii. Perkinson predicts that having the Obama library in Honolulu would be a “major tourist draw,” and given recent statistics he’s probably right. The 13 libraries in the NARA system received nearly 2 million visitors in FY 2011. Having a presidential library can have a deep and positive impact on a community, asserts Benjamin Hufbauer, professor at University of Louisville and author of Presidential Temples: How Memorials and Libraries Shape Public Memory. “The best example is Little Rock,” he says. The Arkansas capital “was a distressed economic area and not that good-looking . . . . [Bill] Clinton put his library there, and then a lot of other businesses decided to move in,” creating a “renaissance” in the city.

Presidential libraries themselves have grown exponentially over the years, Hufbauer adds. The Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library and Museum was built for $376,000 in the 1930s; equivalent to around $6 million today. Compare that to the $250 million budget for the George W. Bush Presidential Center, which is scheduled to open on the campus of Southern Methodist University (SMU) in Dallas in April 20r3. The George W. Bush Foundation is raising funds to support the facility’s design and construction.

Though he was born in Connecticut, George W. Bush chose Texas to host his library because the state is “very important to him, and he moved here when he was quite young,” says Director Alan Lowe. Though there were several sites vying to host the institution, SMU won out because of its “great location and excellent support from its faculty and alumni,” Lowe adds. (It probably didn’t hurt that Laura Bush is an SMU alumna.)

Though he was born in Connecticut, George W. Bush chose Texas to host his library because the state is “very important to him, and he moved here when he was quite young,” says Director Alan Lowe. Though there were several sites vying to host the institution, SMU won out because of its “great location and excellent support from its faculty and alumni,” Lowe adds. (It probably didn’t hurt that Laura Bush is an SMU alumna.)

The library is temporarily located in Lewisville, Tex., as the Dallas location prepares to accommodate more than 70 million pages of documents, approximately So terabytes of electronic information (including more than 209 million e-mails). 43,000 artifacts (primarily gifts to the president and first lady) and an immense audiovisual archives, including nearly 4 million photographs. Along with a space to research these records, the building will include permanent and temporary exhibitions spaces, an auditorium, multiple classrooms, a “Texas Rose Garden” and a full-size Oval Office. (“You can sit on the furniture!” Lowe promises.)

When it comes to content, the Archivist of the United States has final authority, which passes down to the library directors he or she appoints. But while directors get the final vote (or veto). the institutions’ namesakes obviously carry a good deal of sway. George W. and Laura Bush are both actively participating in planning his center, Lowe reports, down to the details. For example, the permanent exhibition is framed on four principles that he says are important to the former president and that reflect aspects of his time in office: responsibility, freedom (related to the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan), opportunity (No Child Left Behind and education reform) and compassion (AIDS relief in Africa).

The Bushes have also indicated a few specific objects they want to see included. “There are certain items that we know are important to him and that are important to telling the story of the administration,” Lowe explains. One is the bullhorn the president used at the World Trade Center site after Sept. n, 2011. “We knew from the beginning that that was important to him, and it’s important to us, so we made sure it was included.”

George W. Bush hasn’t nixed any artifacts, Lowe says. And while the exhibition will show the president’s perspectives on many issues, Lowe says that the library’s working relationship with the Bushes will “ensure that the exhibition that comes out of it is professionally done and won’t duck any difficult issues.” The overall strategy, Lowe says, is to “just put the information out there and let people make up their own mind.”

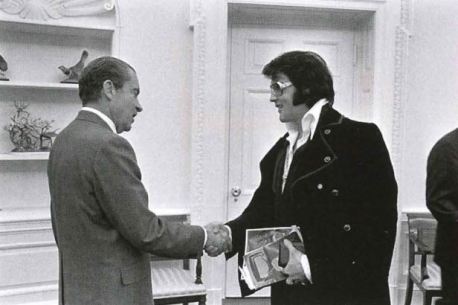

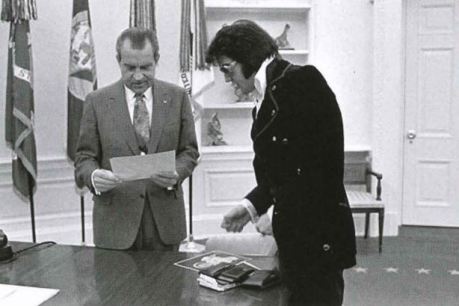

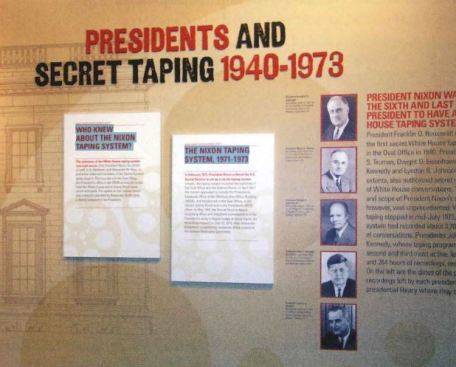

Of course, the way this information is presented will influence visitors’ perceptions. This has posed a difficult challenge for presidential libraries, especially considering that the presidents’ foundations (a.k.a., the funders) generally are staffed with supporters, if not immediate family members. The Richard Nixon Foundation ran the Nixon library in Yorba Linda, Calif., for 17 years before NARA took over in 2007 and the foundation moved to an advisory role. During that time, the library displayed an exhibit on the Watergate scandal, titled “The Last Campaign,” that struck some critics as one-sided. The Washington Post reported in 2007 that “library visitors were told that the Watergate scandal was really a ‘coup’ by Nixon’s rivals and that the investigative reporting team of Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein offered bribes for their nation-shaking scoops.”

The National Archives appointed a new director, Timothy Naftali, to create a more objective exhibit. The revamped Watergate gallery opened in March 2011 with a much less gentle stance on Nixon’s actions and featuring new displays such as “Abuse of Power,” “The Cover-Up” and “Dirty Tricks.” The foundation didn’t seem pleased. None of the board members, who include Nixon’s daughters and his brother, attended the ribbon-cutting ceremony. In a statement, board chair Ronald H. Walker described the exhibit as “one interpretation of the events that led to President Nixon’s resignation in 1974” and urged visitors to visitors to “consider the President’s life in full- the peaks and the valleys” instead of focusing on this “one chapter.” That fall, Naftali resigned from his post.

The working relationship between the library and foundation is “not without its whitewater,” acknowledges Sandy Quinn, president of the Nixon foundation, who notes that NARA is finalizing the selection of a new director for the Nixon library. While the collaboration “didn’t work out very well with the first director, we’re optimistic it will with the second one,” he adds.

At the same time, Quinn acknowledges that a battle may have been unavoidable. “I don’t think the Nixon advocates, which most of us are, are ever going to be fully satisfied with a Watergate presentation. That probably isn’t going to happen,” he says. “But what we were told is, ‘We want people to be able to make up their own mind.’ … Well, there was a Watergate exhibit up and it was Richard Nixon’s point of view. Why not leave that up and then on the other side put your version of it? Then at the end, you could say, ‘OK, you heard Nixon’s point of view, you heard the critics’ point of view, now make up your own mind.”‘ That idea was never considered, Quinn says.

Olivia Anastasiadis, curator of the Nixon library, came onboard in 1991. She says she has a “great relationship” with the foundation but acknowledges that the library’s and foundation’s missions don’t always coincide. “It becomes a conflict because they have to . . . show all the positive aspects of the president. We do that also, but we have to balance it with history and what actually happened. So sometimes there is an issue of interpretation.”

The struggle typically gets easier with time, says Donius at the Office of Presidential Libraries. “Anytime you have living history as opposed to discussing history that’s 200 years old, it’s still very current and fresh. We try to respect that there’s really a life cycle with the museum exhibits.” As is planned for the George W. Bush library, the first exhibition usually reflects the president’s view on his or her administration’s accomplishments. “But as time passes and more research is done, we’re able to reflect it differently,” Donius explains.

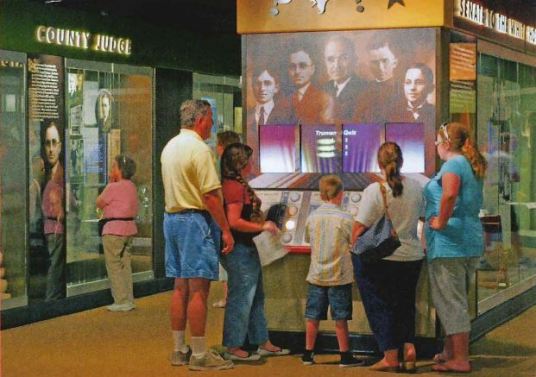

Donius cites the Truman Library as an example of this new reflection. Opened in 1957, the library underwent a $22.5 million renovation in 2002 that upgraded both the physical structure and the educational content. This included a revamped presentation on one of the key issues from Truman’s presidency: his approval of the use of atomic weapons at the end of World War II. The library decided to address the issue head-on, says Michael Devine, who took over as director when the renovation was already underway. The exhibit on atomic weapons aims to “explain to viewers what Truman knew at the time that he approved the decision to go ahead.” It presents differing opinions, juxtaposing laminated copies of Truman’s letters to his wife and friends with sometimes-caustic political cartoons and dissenting opinions of world leaders.

“It’s a story that has to be told, and we try to tell it with as much information as we possibly can and let the viewers make their own decisions,” Devine explains. Though the libraries do want to show the good side of their presidents, “it’s always a challenge not to get too carried away with hero worship,” he adds. “All presidents, including Truman, had their flaws. . . . One can always see in every president’s decisions opportunities that were lost or decisions that, in the light of 20 or 30 or so years of hindsight, might be bad decisions. I think that it’s important that presidential libraries at least make the effort to be as objective and balanced as possible in presenting the story to the public, and not avoid controversial subjects.”

As Obama has at least a few more months, and potentially a few more years, in office, it’s hard to know what issues the Obama library will have to tackle once the president decides where he wants it to be. And though it has a location, the George W. Bush library is still sorting out which issues it will take on in its exhibits. For now, Director Alan Lowe is trying to manage expectations. “I always say to folks, ‘An exhibit can’t be everything to everybody,'” he explains.

]oelle Seligson is associate editor at the Freer/Sackler, the Smithsonian’s museums of Asian art, in Washington, D.C., and former associate editor of Museum.

Comments