Throughout the Annual Meeting, I became curious about how we, as museum professionals, share our learning experiences with each other. I found that my favorite speakers were master listeners—those who elevated other voices in addition to their own.

The Annual Meeting offered many opportunities for listening. On Tuesday afternoon, I joined roundtables in the Open Forum on Diversity, Equity, Access, and Inclusion. In a discussion on intersectional feminism led by designer Margaret Middleton, the group asked, “How do we turn white women into champions, not just for their own issues, but for all?” How can we use our positions to listen, so that we might “raise all the boats” in pursuit of equity? To that end, Dr. Johnetta Cole reminded us of the value of “getting into each other’s lived experiences” because it sets us up for deep learning. She suggested that we read more fiction and narrative accounts. (Roundtable recommendations include work by Zora Neal Hurston, Audra Lorde, bell hooks, Janet Mock, Amy Tan, Joy Harjo, and Hellen Keller.) In the rest of the discussion, the group asked questions of each other’s lived experiences (or, those of each’s colleagues) to deepen their understanding and uncover new questions about intersectional feminism, workplace practices, and harassment, finding mentorship as black women in museums, etc. During conversations like these, practiced listeners draw authentically from their own and others’ lived experiences. It was as if I was not only hearing from those at the table but rather as if I were hearing from everyone they’ve ever listened to before, too.

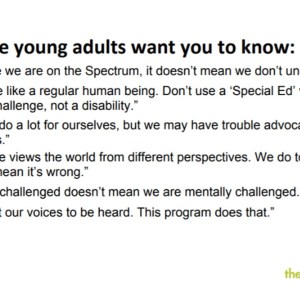

I encountered a few “master listeners” in conference sessions. In a session called “Growing in the Museum: Engaging Young Adults with Cognitive Disabilities,” Beth Redmond-Jones of the San Diego Natural History Museum presented about a collaborative project of museum professionals and young adults on the autism spectrum called Spectrum – Social Stories Project. (I am a bit biased here – RK&A, a research, planning, and evaluation firm where I am a Research Assistant, evaluated Spectrum last year). During the project, she asked the young adults what they wanted museum professionals to know about them, and shared their responses with us verbatim:

Museum educators are poised to become master learners from their audiences—and to then turn around and share that information with the field, so we can all better serve the audiences we say that we want to. This is how we go about constructing knowledge together—by acting as learners.

Skip over related stories to continue reading articleThinking about speakers and listeners, I am reminded of Ursula Le Guin’s thoughts on human conversation: “The living response has enabled that voice to speak. Teller and listener, each fulfills the other’s expectations. The living tongue that tells the word, the living ear that hears it, binds and bond us in the communion we long for in the silence of our inner solitude.”

If we approach our work as learners, we continually reconstruct our knowledge of museum audiences, the role of museums as institutions, and the human experience. I remain so thankful for the opportunity to learn from each other’s collective experience at the Annual Meeting, and for the prompt to consider how a speaker shares their learning. Since then, I’ve been thinking more about the role of museum educators—and evaluators—as a system of learners.

How, if at all, in your professional practice do you speak as a listener?

Comments