Until we perfect my AI-powered digital avatar, I rely on an informal network of correspondents to cover critical events taking place around the globe. In today’s guest post, Sarah W. Sutton reports from the Global Climate Action Summit (GCAS) that took place in San Francisco last month. Sarah is the Sector Lead for Cultural Institutions for We Are Still In and principal of Sustainable Museums—you can read more about her work at the end of this essay.

During the Global Climate Action Summit (GCAS), businesses, investors, states and coalitions, higher education and cultural institutions were all announcing successes and/or establishing new commitments that support the goals of the Paris Agreement. They were telling the world how they would limit their impacts on the environment and improve their roles in creating more sustainable, livable communities. I was looking for glimpses of future connections between museums and other sectors as part of the sustainability movement. From five days of varied sessions I found supporting evidence for three areas I believe are touchpoints for environment and climate action as they relate to museums: a significant transfer of wealth to environmental causes, the deepening and broadening of citizen-based environment and climate action, and an overwhelming need for culture sector mapping and measurement.

Museums as Recipients of Environmental Reparations Funding

I anticipate a stunning wealth exchange between environmental violators and environmental support institutions in the next fifteen years, and, much sooner, between companies and other agencies that adopt the United Nation’s Sustainable Development Goals as priorities and are shifting their funding to those organizations that can help them fulfill those goals. Cultural institutions are perfect partners in that work. I see a few pre-public situations developing, and some public ones.

We have had a foreshadowing of that with the Volkswagen and “Dieselgate” in which the car manufacturer was found guilty of “circumventing emissions controls systems” to allow cars to run in violation of clean air emission standards. The EPA ruled VW must pay into a trust fund for states to create opportunities for reducing emissions. Some states have used that to fund charging stations and grants of electric vehicles. At GCAS, during the BiodiverCity Summit at the Exploratorium, I saw another environmental example: California’s Department of Transportation paid a settlement including $5.5M for remediation of Mountain Lake, which has been polluted with lead and other runoff from Highway One’s poor drainage. The Presidio staff chose to use the payout to reach beyond cleaning up the lake and restore ecosystems and biodiversity through partnerships and science. They’ve planted submerged aquatic vegetation to generate oxygen in the natural system, supporting the comeback of two native species, the three-spined stickleback (a fish) and the rare and declining California floater mussel (which requires the stickleback as a host during the growth of young). The Presidio staff went on to support the dwindling native western pond turtle population with the help of the San Francisco Zoo, Oakland Zoo, and Sonoma State University

Suits against fossil fuel companies will result in penalties that have much broader remuneration targets with no clear path to individual beneficiaries. Rather than resulting in targeted remediation projects, the rulings could mandate allied actions of expanded health services, public education and training, research and innovation, in-situ repairs and restoration, and ex-situ protection and cultivation. Museums might be eligible to attract funding on behalf of their communities if their activities align with the goals of specific awards. They might even be the host of trust funds for continued public engagement or restoration management and monitoring. But for this to happen, we have to build awareness that cultural institutions are the ideal trust agents, and that our impact can reach far beyond the palliative “educational exhibit.”

National Climate Service

The Great Transformation (as someone called it) to a future where humans are part of a thriving planet will require a dramatic shift from the ways we manage the world’s resources. To truly transform ourselves we must change the way we think and behave. How can we find out fast enough which changes will make the most difference? I think we must deploy as many explorers as possible to develop the knowledge of how to identify and recreate or support the lost and fading ecosystem relationships that keep our planet comfortable for us, and economic practices that do not. We need researchers, implementers, and communicators. I think the Corporation for National Community Service should add a sector, which I’ve dubbed Climate Corps. This national environmental service option could address climate change issues by deploying ten to twenty-thousand annual participants, of all ages and abilities, for a two-year cycle of service, including work on land and ocean restoration plus public engagement. If participants complete the service, they should be awarded the equivalent of a two-year degree for their acquired literacy and experience in the field.

Alas, the current environmental participation in existing national service programs is not sufficient to meet the nation’s needs. As we wait for the establishment of something like Climate Corps, your institutions can create and engage your own versions. Think about how you could use your archives, collections, heritage farms, gardens, landscapes, creeks, lakes, and open space as research labs. Aggressively staff them with nearby community college or university students, and with citizen scientists transitioning into retirement, or with grade-school students. The indigenous and non-indigenous history of your area is valuable to this work, just as valuable as modern science. Mobilize these community members as your own climate corps and encourage other museums in your community do so as well. You’ll be fostering education and engagement, demonstrating your relevance, driving up your community value, and helping to save the planet.

A Climate Resources Map of the Cultural Sector

With so much to be done, where should we start? I think we could answer that question by creating a map of the cultural sector’s climate impact to give us a baseline of practice and to identify valuable gaps and opportunities. Such a map would enable us to measure improvements and focus our energy on best practices while visualizing opportunities for innovation and partnerships to accelerate and scale change.

Though deep down I have always understood that the personal inconvenience of large-scale data collection pale in comparison to the value of the data, I believe funders ask the wrong questions at the wrong time. Requiring hundreds of grantees to enter pages of information on finances, participation, and programs overlooks other important impacts. And the process often misses contextual details that are critical to understanding how an institution fits into a community and an environment, and how it may relate with the community and its needs. Nor does it help the grantee or the funder visualize what they haven’t done, and what they might have overlooked. The key strokes seem to disappear into someone else’s domain—permanently. We need a different way to understand our sector and to connect our resources to others.

Without a map and visualization data, how do you know that the food waste among cultural institutions in your area is enough to feed the current homeless population in your city three meals weekly? Without a map, how do you know if there are enough rooftops among the downtown cultural institutions to create a community solar program without a map? Without a map, how do you recognize that your parking lot and gardens could create a wildlife corridor among a bunch of postage stamp greenspaces? The baseline for a climate and culture data map is knowing institutions’ energy and water use, and waste production so that we can identify and measure basic emissions and impacts, and demonstrate our future reductions. Then, to visualize paths to scale change we also need to know where an organization is sited, its footprint in a community, and its adjacencies and proximities. This information allows planners to identify relationships that offer local opportunities for travel efficiencies, open space sharing, or research resources, for example. We also need to be able to “see” organizations’ missions and strategic interests to identify previously unnoticed alignments of research interests and resources of institutions. Data projects have been valuable for describing ourselves; now we need projects that help us map how we will make a difference. We must move cultural data information projects past the once-novel point of documenting the economic impact of the sector to documenting the climate impact and opportunities of the sector.

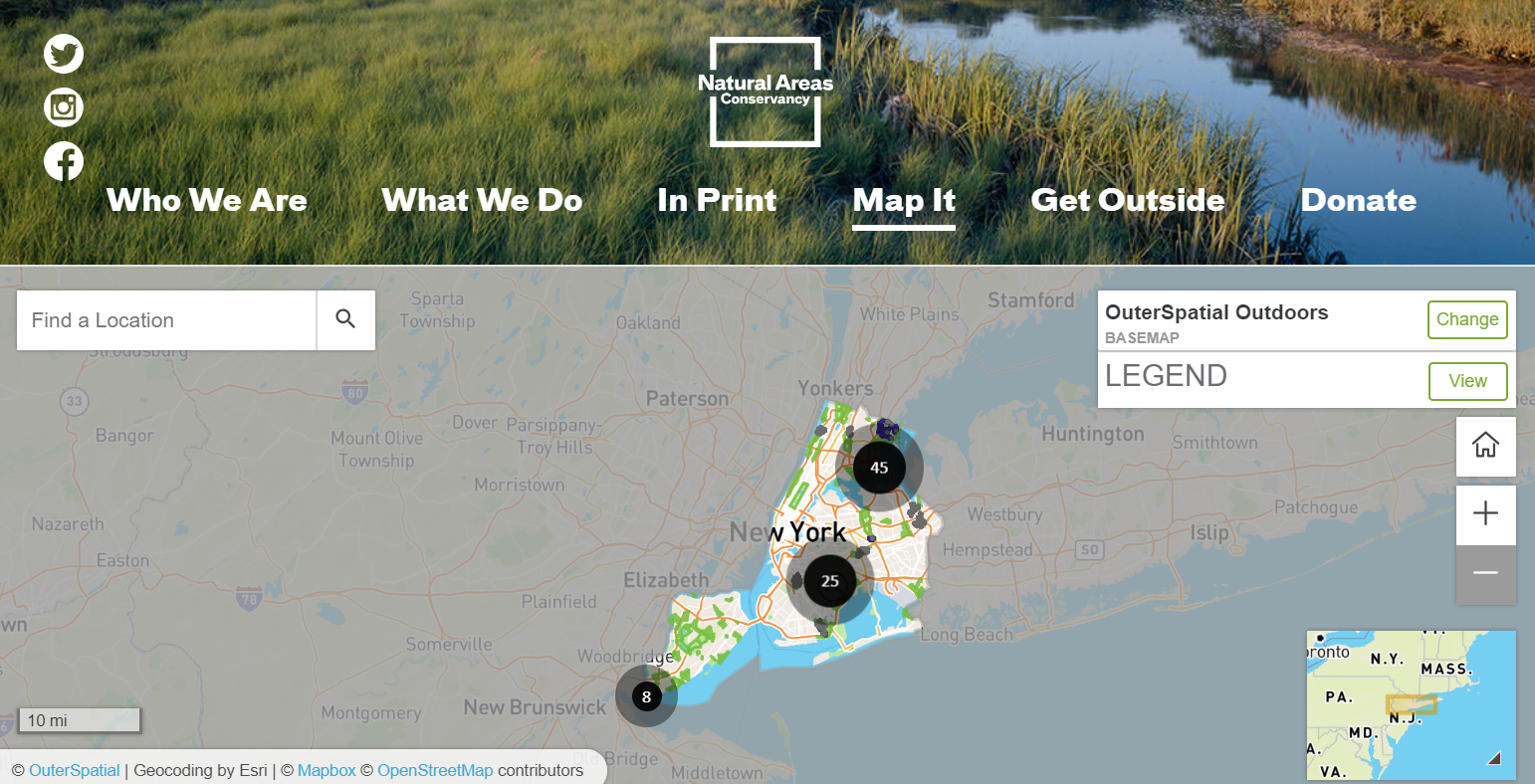

During the BiodiverCity presentations I cheered inside as I learned about the mapping of the Natural Areas Conservancy in New York City. Sarah Charlop-Powers, NAC’s Executive Director and Co-founder, explained how the numbers and images helped them understand the restoration and climate adaptation work that was needed to efficiently and effectively begin to protect the natural areas of the city. Due to the research process, they now engage institutions and residents in restoration projects, and have activated partnerships and funding that are helping protect and restore spaces and conduct new research while increasing public engagement. Their data and mapping helped them create The Forest Management Framework, a data-informed 25-year plan, with “the process, costs, steps, recommendations, best practices, and goals, for forest management in NYC” bringing 7,300 acres of forests under active management (and averting passive loss).

The Forest Management Framework shows us what a map of climate resources and actions in the cultural sector could look like! The Nature Areas Conservancy’s work is an example of how mapping a resource, in our case the cultural institutions of a country, can help strategically define operations, engagement, and strategic management for climate mitigation and adaptation for a sector. So let’s consider new approaches to cultural data projects, approaches that leverage those keystrokes for climate response.

Bringing it all Together

The future is climate.

With a Cultural Sector Climate Map, we could help our field determine how we can use our unique abilities and resources to further climate work. The map would help us make the case for specific applications of the wealth from environmental reparations and it would tell us how best to deploy the National Climate Service troops when they eventually show up to help.

Skip over related stories to continue reading article

Comments