I’m using the 10th anniversary of CFM, and the ninth year of this blog, as an occasion to revisit some of our most widely read posts. Today I’m re-posting an essay by Sean Kelley, Senior Vice President, Director of Interpretation, Eastern State Penitentiary Historic Site. Originally titled “Beyond Neutrality,” it’s racked up an astounding 18,000 page views since it was published in 2016. I’m sharing it again now because you have the opportunity to hear Sean talk in person about tackling difficult topics. He will be keynoting at “Leading Forward: Shaping the Future of Your Historic Site,” a working meeting being held March 23-24 at Mount Vernon, organized by the Alliance and our Historic Houses and Sites Network. There is still some space available, so you can register to attend one or both days (Sean is speaking on Saturday the 24th).

Here at Eastern State Penitentiary we are rewriting our mission statement to remove the word “neutral.”

We believe that the bedrock value that many of us brought into this field—that museums should strive for neutrality—has held us back more than it has helped us. Neutrality is, after all, in the eye of the beholder. At Eastern State, more often than not, the word provided us an excuse for simply avoiding thorny issues of race, poverty and policy that we weren’t ready to address.

Most visitors to Eastern State are white. Most are middle class, and most are tourists to Philadelphia. Ten years ago I would have argued that leisure travelers don’t want to explore the complex and troubling root causes of mass incarceration. At the time we did commission artists to explore these issues at the physical edges of our property, but our tours and historic exhibits focused squarely on the past. Nobody complained.

In some small ways I was probably right. Bipartisan support for criminal justice reform has grown dramatically in recent years. Ten years ago our staff was tiny, our resources modest, and our board of directors in transition. Perhaps we weren’t ready.

But mostly I was wrong. Development of our first Interpretive Plan in 2009 forced us to look more critically at our choices. Looking at a map of programming around the site, I had to conclude that our version of “neutrality” was mostly taking the form of silence. As a coworker said at the time, “Oh, we talk about race and the US criminal justice system every day…our silence tells visitors exactly what we think about it.”

I thought neutrality would create a safe space for visitors, but it was becoming clear that this space wasn’t safe for Americans who have experienced mass incarceration up close, within their communities.

Skip over related stories to continue reading article

We have tried to shift our focus to effectiveness and inclusion. We have found that many leisure travelers really will engage with these difficult subjects, but core elements of museum craft become more important than ever. Experiences need to be social, multi-generational, interactive and accessible to visitors who don’t typically learn by reading alone. They need to genuinely value the wide perspectives and personal experiences of the visitors themselves.

- represents the massive per capita growth of the US prison population over the last 40 years;

- compares the US Rate of Incarceration to every other nation on earth (we are highest by an enormous margin),

- divides nations into those that practice capital punishment and those that do not;

- tracks the consistent and disturbing racial disparity in our prison population over time.

Every visitor encounters The Big Graph. It concludes the main audio tour and is incorporated into every school tour. The text on signage is direct and blunt. The audio tour asks “So why does the U.S. need to imprison so many people?” To our surprise, visitors consistently report that The Big Graph feels “neutral.”

In developing the companion exhibit, Prisons Today: Questions in the Age of Mass Incarceration we faced a crossroad. We had dipped a toe into the pool of honesty about our perspectives, but we had maintained the illusion of neutrality. The new exhibit was shaping up to be a deep dive into issues of policy, race, enforcement and outcomes. Were we really going to say “on the one hand….?” It felt patronizing.

There are too many Americans in prison. Our staff knows it, our advisors know it, our Board knows it. And so we eventually united around a statement: “MASS INCARCERATION ISN’T WORKING.” That phrase opens the exhibit in 400 point block letters.

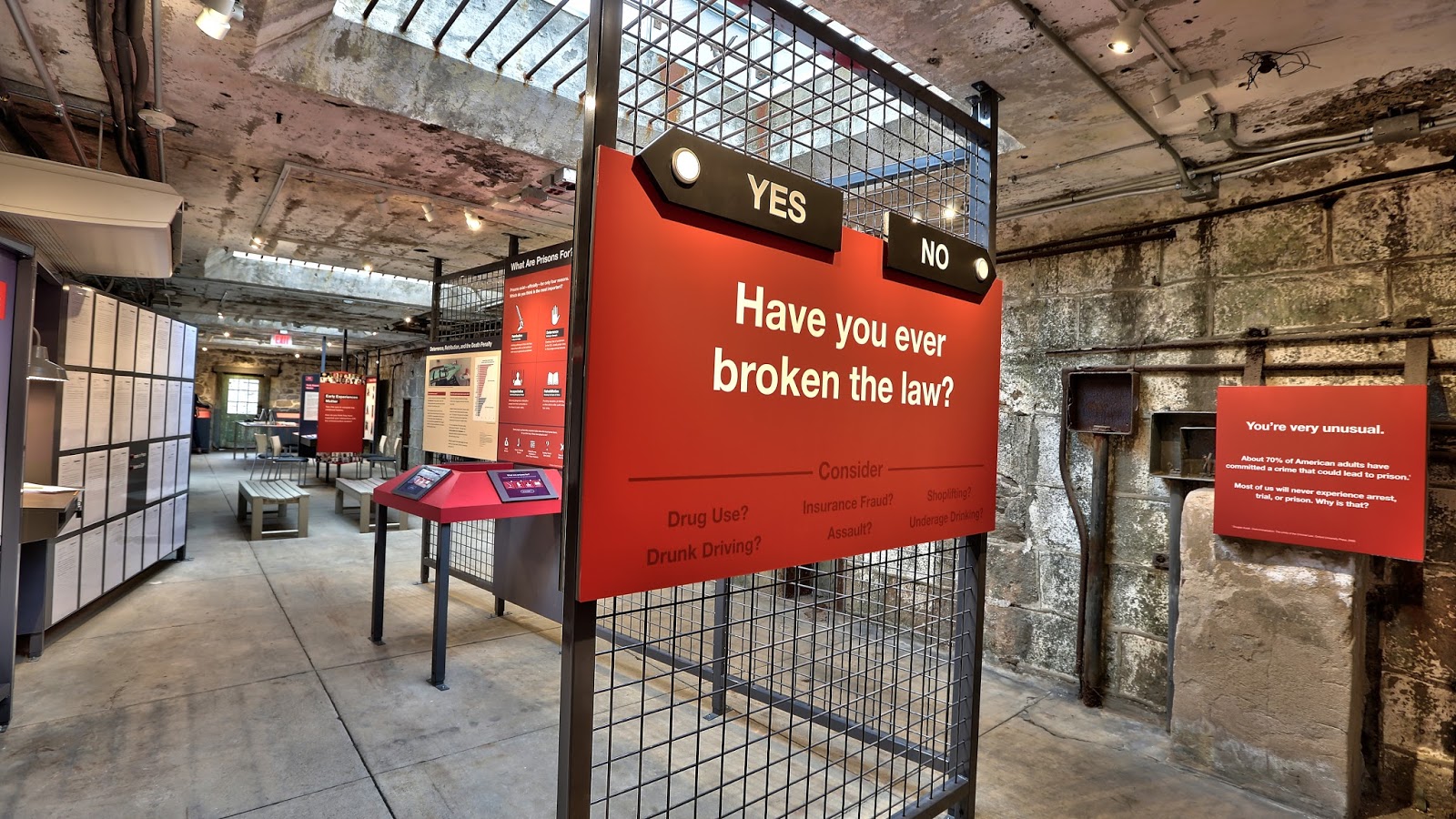

Nearby a seven-screen video tracks the political rhetoric that has driven criminal justice policy since the 1960s. The video ends with admissions of humility and compassion from a set of current political leaders, stressing voices from the political right such as House SpeakerPaul Ryan. At a later point in the exhibit, visitors are forced to walk through one of two corridors, based on their willingness to admit if they’ve ever broken the law. Admitted lawbreakers are confronted with artist Troy Richards’ installation, asking if they see themselves as “criminals.” He invites these visitors to leave written confessions. He also mixes visitor confessions with confessions from men in and women living in prison. Visitors try to guess which is which. They can’t.

If there’s a message to this exhibit, aside from the failure of our criminal justice system to justify the scale of its growth, it’s a call to empathy. Exhibit cases contain objects on loan from members of our tour staff who have been recently incarcerated. A beautiful and troubling film by Gabriela Bulisova tells the stories of six men and women impacted by the criminal justice system. A reading table includes “The Night My Dad Went to Jail” (written for children 5 – 8 years old). Visitors are invited to “Send a Postcard to Your Future Self,” using a digital kiosk to create personalized electronic postcards that will arrive in two months, one year and three years. The postcards remind visitors of what they were thinking during their visit, and recommend ways that they can influence our nation’s rapidly changing criminal justice policies based on their responses to the exhibit content.

The journey to create this programming has changed our organization. Our Board of Directors now includes a scholar who studies race and incarceration and teaches inside prisons. It also includes a reentry professional who was himself incarcerated for seven years. [Full disclosure: like many museums, we lack still appropriate racial diversity on our management team; we know have work there to do.]

Our visitors—about 220,000 last year—aren’t expecting this programming when they arrive. Most want to see Al Capone’s cell or the site of the doomed 1945 “Willie Sutton” escape tunnel. I’ve grown to think that makes them the perfect audience to engage. Exit surveys conducted after The Big Graph’s completion reflect only 4% saying that the inclusion of contemporary content detracted from their visit. A full 91% of visitors reported learning something thought-provoking about today’s criminal justice system. The Prisons Today exhibit has only been open a few months, and summative evaluation isn’t yet complete. Press coverage and social media comments are encouraging.

Our audience has grown by more than 20% since we began addressing these complex and troubling aspects of American life. I once feared these subjects would suppress our attendance. I feared they would divide our Board of Directors and scare potential funders. I feared they’d harm staff morale, including my own. And I thought neutrality, whatever that meant, had to guide all of our programming decisions. I was wrong on every front.

Now I wonder what other misguided beliefs we’re leaving unexamined.

Comments