The COVID-19 pandemic is creating new norms that discourage touching all manner of objects to curtail the spread of the virus. However, when public spaces reopen, understandable concern about disease transmission may lead museums to prohibit tactile exploration of objects, creating an unintended access barrier for people who are blind. We are tactile artists and designers who hope to start a conversation in the museum field by offering for consideration our expertise producing re-usable tactile handouts.

We imagine a scenario where visitors could borrow tactile handouts, use them for reference as they tour an exhibit, and then return them to the museum for treatment and later re-use. In this post, we describe several techniques for creating raised line images embossed on paper or plastic pages, and we also discuss making 3-D-printed replicas of objects.

In our opinion, this approach would minimize concerns of sharing materials among visitors, because participants would access their own tactile handouts. Physical distance could be maintained between visitors who would not need to gather around a single table or display case to touch the same objects. Furthermore, tactile handouts could be added to outreach materials, for example, in traveling trunks that are shipped to teachers for use in their classrooms.

Creating Tactile Handouts

Ann Cunningham has created numerous tactile images for use in educational and museum settings. She has used various techniques, described here in order from simple to complex.

Raised line drawing boards ($50-200) provide a low-tech solution that is easy to learn. We recommend the Sensational BlackBoard, because pictures can be drawn on standard copy paper using a medium ballpoint pen. The technique is easy to learn, and copies can be made quickly.

Raised images can be made from embossed paper in a similar manner to that for making greeting cards. A commercial press with access to equipment and dyes could print multiple copies of embossed paper images in color. The resulting tactile handouts would be interesting to all visitors.

A Cricut Maker can be purchased from any craft store. This brand, or a similar CAD-driven craft cutting machine, is a mid-range solution ($200 to 400) useful to assemble images created out of multiple layers of paper or other sheet materials. In this method, images can contain color, making them good options for people who have low vision or as a multi-sensory experience for sighted audiences.

In our experience, many people who are blind appreciate the clean images produced using micro-encapsulated paper, commonly known as Swell Paper. A machine heats the micro-encapsulated paper, forming a raised line. The machine is relatively expensive ($2,500-3,000), and sheets of swell paper are between $1-$3 each. This method allows museum personnel to print full-color images and raise the black lines to create tactile images.

Finally, a thermoform machine ($2,000-3,000) shapes plastic sheets over a master image to produce raised images. Cunningham documented her multi-step process of making a tactile image of a bat commissioned by the National Braille Press. First, she modeled the bat in clay. Next, she created a plaster cast of the clay model. Then she used the plaster cast to create a heat-resistant, flexible plastic mold. This mold was shipped to the National Braille Press for production.

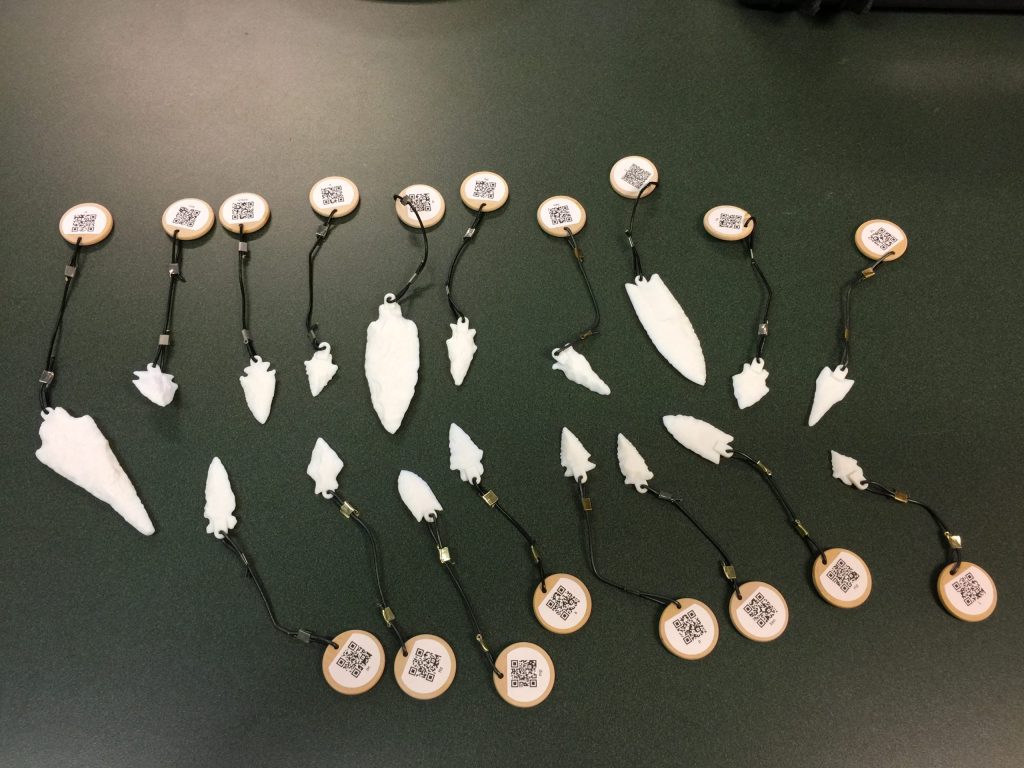

Some museums have produced tactile replicas using 3-D printing technology. Preparing an object for 3-D printing involves scanning it with a laser system to create a mathematical model of the physical surface and form to be reproduced. This digital file is known as a 3-D model, and it can be sent to a 3-D printer to produce a physical replica of the original object. The digital files can be saved, and many prints can be made from a single 3-D model.

The primary investments of time and money for producing tactile handouts using any of the methods described here are incurred in the purchase of equipment, and in the time and skill necessary for the design and production of the original handout. Once the original tactile handout is designed, copies can be produced for the cost of additional materials. We encourage museums located in geographic proximity to seek partners such as maker spaces, to share equipment and materials costs. In this scenario, collaborations between institutions would foster the development of knowledge and skills necessary for production of tactile handouts, which, in turn, would lead to increased accessibility for people who are blind or have low vision.

Adding Information to Tactile Handouts

Another benefit to producing tactile handouts is that they can be linked to audio or text files so that a visitor could independently access information that might be printed on a sign or an exhibition label. Visitors could read or listen to information about tactile handouts on their own devices if content is designed to take advantage of the accessibility features built into personal smartphones or tablets. Some examples of accessibility features include color contrast, screen or print magnification, voice command, and screen readers (voice output) such as Voice Over for iOS and Talk Back for the Android operating system. Projects that allow visitors to use their own devices can be both accessible to people who are blind or have low vision and inclusive to sighted audiences.

This paper describes and compares two projects that integrated tactile exploration and technological solutions to access information about the objects on display. One project tested the use of QR codes that were attached to 3D-printed replicas. The other relied on near field communications (NFC) beacons to access labels for an exhibition of tactile art. The paper explains the technical requirements of each accessibility solution, and it demonstrates how people who are blind accessed information that is associated with tactile exhibits.

Another technical solution that we can recommend is an app called Tactile Images. This app allows an image to be tagged with zones of information specific to each area. Later, a user can retrieve these descriptions for reference while exploring the tactile graphic independently. The online library includes tagged images that can be downloaded for free.

Tactile Panels and Physical Distancing

The concept of reusable tactile handouts could be scaled up from single objects to new exhibits by installing tactile panels at intervals to maintain physical distance between visitors. Panels could be placed to encourage one-way flow of visitors through the exhibit.

Our idea for this approach is loosely based on an interactive art installation titled “Mission to Nocterra,” created by Matt Gesualdi of Tact-Ed in partnership with the Colorado Center for the Blind. This pitch-black puzzle room debuted at Maker Faire Denver in October 2018. In the storyline, scientists found an alien vessel containing five artifacts from the planet of Nocterra, whose sun emits all wavelengths except visible light. Because the inhabitants of Nocterra evolved without the sense of vision, the “vessel” was represented by a dark room where each of the five walls contained a unique puzzle. Each person was assigned to solve one puzzle, and visitors were separated by working on their own puzzle.

Conclusion

We hope that the approaches presented here will encourage a dialogue about best practices for tactile exploration in the post-COVID-19 era. We encourage anyone wishing to share ideas or seeking advice for specific projects to visit our websites and follow us on social media. With forethought and advanced planning, we believe that museums can produce re-usable tactile handouts to provide access for people who are blind, and to offer multi-sensory experiences to all visitors.

About the authors:

Dr. Cheryl Fogle-Hatch is an independent consultant who researches and develops multi-sensory content for museums and other cultural organizations. She believes that creating exhibit content with tactile and audio components can enrich the experience of all visitors. She earned a Ph.D. in anthropology from the University of New Mexico, where she taught 100-200 level college courses in archaeology. She also designs and leads hands-on science activities for high school students in programs run by the National Federation of the Blind. She can be reached at info@museumsenses.org. For more information about her work, please visit her website at https://museumsenses.org, or follow her on Twitter, Facebook, or LinkedIn.

Ann Cunningham has exhibited her work at the Denver Museum of Art, the Woodson Art Museum in Wausau, Wisconsin, and in various public buildings and parks both nationally and internationally. She believes that humans are exquisitely prepared to engage artwork on all sensory levels. Ann teaches art classes at the Colorado Center for the Blind and she has taught stone carving, ceramics, bronze sculpting, collage, and assemblage. She developed methods to teach tactile drawing that help students to organize 3D information onto a 2D picture plane. For more information, visit her website at acunningham.com, or follow her on Instagram, Twitter, Facebook, or LinkedIn.

Matt Gesualdi of Tact-Ed has been researching design for the blind and visually impaired community since 1998. He has made three tactile exhibits for the Denver Art Museum, many tactile scale models, and two interactive, immersive exhibits including a pitch-black puzzle room, Mission to Nocterra, for Maker Faire Denver 2018’s main exhibit. Matt has a Bachelor of Arts degree in Industrial Design from the Art Institute of Colorado and a Master of Arts in Educational Leadership (emphasis on teaching the visually impaired) from Argosy University Denver. He is in the Denver Tactile Media Alliance and the Denver Art Museum’s Access Advisory Group. For more information, visit the Tact-Ed website, or follow him on Twitter, Facebook, or LinkedIn.